Rise of the Railway – Part 2 Further development of railway operations in Eastleigh By Chris Humby (from a talk first presented in October 2015)

In the article Rise of the Railway – Part 1, the Railway Institute was briefly mentioned. The man charged with overseeing the construction of the Railway Institute, was the Superintendent of the newly constructed Carriage and Wagon Works, Mr William Panter. The building of the Institute was completed within 8 months. William Panter was also chairman of the Eastleigh Local Board and continued as chairman of Eastleigh Urban District Council when it was formed in 1893. Council meetings were held at the institute until the Town Hall was built some years later.

The educational facilities afforded by the Institute were of immense benefit, not only to the railway employees who took advantage of these facilities, but to the railway company itself, supporting the training necessary to ensure a continuity of craftsmen in their employ. Beside the formal activity involving education and politics, the Railway Institute led the way with social activity in Eastleigh, particularly for those employees who had re-located from London. This picture shows an early charabanc tour assembling outside the club on the corner of Leigh Road and Upper Market Street.

Negotiations for the purchase of the Cricket Field in Leigh Road, adjacent to the Institute, were concluded in 1896. The London and South Western Railway donated £2000 towards the purchase price and the new chairman of the Railway Company, Mr Wyndham Portal attended the “Handing Over” ceremony and declared that “the deed presented conveys this piece of ground now and forever to the charge of the Council in authority on behalf of the people”. The general management of the Recreation Ground initially came under the auspices of the Railway Institute.

The London & South Western Railway Company also purchased land at the end of Fisherman’s Lane (re-named Dutton Lane in honour of Ralph Dutton), to be used as a recreation ground.

The Railway Company built a large stadium providing football pitches, a cricket pitch, and a banked cycle track, as well as facilities for athletics. Eastleigh once had one of the finest cycling tracks in the country.

The Stadium became quite famous, and from these images taken during WWI you can appreciate that it was well supported.

Eastleigh grew rapidly and the area around the station was modified in 1895 to support the expanding community. The station entrance was altered and extended forward to provide a new ticket office; The Home Tavern was re-built in the style that is seen to-day; The Junction Hotel was extended and a new hotel, the Crown, was constructed next to the Home Tavern. The Carriage Works was clearly a success, and such was the need for workers that there was an influx of people seeking to be employed in the new industrial complex. By the mid-1890s the population of Eastleigh had grown rapidly from 3,600 in 1891 to around 7000 in 1894. (The population had nearly doubled in three years).

A builder, Jonas Nichols, leased land from Thomas Chamberlayne who owned much of the land around Eastleigh, and laid plans to develop the new town to provide accommodation for railway workers. The provision of housing built by private enterprise was a distinct advantage to the railway company. We generally assume that the workers transferring from Nine Elms were content to do so and an article in the Railway Magazine of 1898 regarding Eastleigh Carriage Works recorded that “during the eight years that they have existed the Eastleigh Works have known no conflict of any kind between employer and workman.” More interesting is a report in the Engineering Magazine from July 1892, some six years earlier which considered that “unfortunately… the speculative builder has got his clutches upon the unfortunate workmen at Eastleigh, many of whom complain bitterly…. We are informed by many of the men that they have to pay just as much for worse accommodation than their old quarters.” The journalist, diplomatically trying to balance this statement, added the comment, “working men, like all classes of the community, are apt to make the most of their grievances.” I personally can’t believe that new accommodation in Eastleigh, in the late 1800s, was worse than the tenement slums of Victorian London, but I can imagine that, as new houses, they were not particularly cheap.

There were problems with the town infrastructure for the incomers and controversy, at the time, centred on the deplorable state of the unmade streets, lack of street lighting and lack of adequate drainage and sewerage in the town. The London and South Western Railway encouraged the formation of a town council and William Panter, the Carriage Works Superintendent, was appointed chairman of the Eastleigh Local Board and continued as chairman of Eastleigh Urban District Council. Other senior railway officials were also members of the council. With the arrival of more railway workers in 1903 and 1910, Eastleigh became a frontier town populated by railway employees, living in accommodation specified by the railway company, and managed by their senior employees. The town was not owned by the railway, but they most effectively controlled it.

Most of the housing in Eastleigh was constructed by private enterprise but recognising that the decision to relocate the Engineering Department from Nine Elms would create an unprecedented demand, the railway company agreed to build cottages in Campbell Road in the early 1900s. These terraced cottages were built to a high standard and were some of the first accommodation in the town to be provided with a bathroom. The Locomotive, Carriage & Stores Committee minutes in February 1904, set the rent for the new block of six Company’s cottages in Campbell Road, due for occupation in April, at 6/- each per week, the Company paying all outgoings. The meeting also approved the raising of the rent of the Company’s cottages in Dutton Lane from 4/- to 5/- per week, as they become vacant. Presumably the higher rent for Campbell Road was justified because of the luxury of bathrooms, which Dutton Lane did not have.

(Picture courtesy of Kevin Robertson)

(Picture courtesy of Kevin Robertson)

A rail track, running down the centre of Campbell Road, was used to bring builders supplies to the houses. Houses adjacent to the “sheds” in Campbell Road, which was named after the then Chairman of the London & South Western Railway, Lt. Colonel the Honourable H.W. Campbell, were constructed by William Whitehead, from Bishopstoke.

Access to Campbell Road was created by a Road Bridge constructed over the main railway line from Eastleigh to Southampton. This bridge provided pedestrian and vehicle access to the new residents of Campbell Road as well as giving access to the new Running Sheds and Locomotive Works. This picture shows houses in Southampton Road on the left and workmen constructing foundations for the walling and ramp that extend from Southampton Road to form the approach to the bridge. The building on the right is the old running shed, which was constructed around 1870 when it was moved from the earlier location, north of Bishopstoke Station. This old running shed was demolished in the early 1900’s when the new larger running sheds were built alongside Campbell Road. The new Locomotive Works office building was constructed close to the site of the old sheds.

By 1903 the new main line loco-engine cleaning and running sheds were opened in Eastleigh. According to an article in the Railway Magazine of January 1903, this was the planned first stage of the scheme towards removing the Locomotive Works from Nine Elms. These running sheds became a major maintenance, operating and fuelling centre for locomotives working on the London & South Western Railway, and later the Southern Railway. They replaced the running sheds we saw in the earlier picture and the running sheds at Northam in Southampton.

According to London & South Western Railway minutes of the Engineering and Estates committee on 26th June 1901, approval was sought for authority to proceed with the construction of the Engine Shed at an approximate cost of £21,000. It was a surprise to me to learn that in the 1930s, when part of the Southern Railway, these running sheds at Eastleigh employed a staff of 550 with 400 of these employed as drivers or firemen. Today an operation of this size would be considered to be one of the major employers in the town.

This diagram of the locomotive depot shows that the running sheds were constructed with fifteen roads. In 1946 Eastleigh shed had an allocation of 131 engines. The layout of the running sheds included offices, stores, sand drying furnace and a lifting shed arranged along one side of the building. The turntable, tank house and coaling stage were located on the opposite side and positioned so that engines coming into the shed could pass on the turntable to be turned and then forward to take water and coal before they entered the shed.

Re-fuelling was a routine function undertaken at any running shed. This picture, taken at Eastleigh, shows 30507, a Urie designed S15 class loco alongside the coaling station with the water tank in the background. The water tank was fed directly from the River Itchen and when cleaned out, apparently, considerable quantities of fish would be found. The tender on these loco’s could hold 5 tons of coal and 5000 gallons of water. A UK gallon of water weighs 10lbs, which means that the tender could be carrying 22 tons of water in addition to 5 tons of coal. I do not know the weight of the fish!!! The reason that so much water was carried was that the London and South Western Railway, with comparatively short mainline routes, did not operate using water troughs, like other regions. A report from 1911 advised that dormitory and mess accommodation was provided under the water tank, so that enginemen away from a home station could be lodged for the night. It is not known when this facility stopped being used but I can only imagine that sleep would be frequently interrupted from the clanking of loco’s, the sound of flowing water and the din from the nearby coaling station as each half ton of nutty slack cascaded down the chute and into the tender, to be followed by an almighty clang as the chute, once empty, swung back up out of the way.

Locomotives could be rotated to change direction of travel at Eastleigh running sheds. Here British Rail Standard Class 80152 is pictured on the turntable with the locomotive works and cottages of Campbell Road pictured in the background. An alternative to the turntable, a triangle, was constructed at the back of the sheds, east of Campbell Road. This was a simple mechanism, which covered a relatively large area and, by use of a series of points, allowed the driver to reverse the direction of the engine.

This picture, taken at Eastleigh in the early 1900s is a family photo of my wife’s grandfather, Harry Chamberlain, who was born in Exeter in 1885. He is pictured as a young footplate fireman with rolled sleeves, waistcoat, and tie, whilst the driver, with oil can, is wearing his jacket and tie. Working on the railway was a privilege and wearing of a tie was expected regardless of the type of occupation. Harry Chamberlain went on to become a driver and lived much of his adult life in Campbell Road. I am no expert on loco recognition and the loco has no identification number to help. I believe that it is an Adams 0-4-2 tender engine “A12”. Most of these Locos were built at Nine Elms between 1887 and 1895 and received overhauls at Eastleigh before they were systematically withdrawn from service and scrapped between 1928 and 1948. They were nicknamed “Jubilees” because they were introduced during the Golden Jubilee of Queen Victoria’s reign. None of this class of engine have survived.

The man appointed to manage the construction of the Running Sheds and new Locomotive Works at Eastleigh was Dugald Drummond, the London and South Western Railway’s Chief Mechanical Engineer. In 1910 the Locomotive Works moved from Nine Elms to Eastleigh under the control of Dugald Drummond and his works manager Robert Urie, who both hailed from Scotland.

To enable him to get about the London and South Western Railway system quickly, Dugald Drummond designed and had built, in 1899, his own personal rail transport, which became known as “Drummonds Bug”. Drummond used this engine on frequent visits to Eastleigh as the building of the running sheds and new works progressed. He continued to travel in it, almost daily, from his home in Surbiton to Eastleigh and back when Eastleigh Locomotive Works was in full production. After Drummonds death in 1912 the loco was little used and was retired to Eastleigh. It was used on an occasional basis to take special visitors on tours of Southampton Docks which at the time were owned by the Company.

1910 is the date that is synonymous with the building of the first locomotive at Eastleigh Locomotive Works, but of course time was needed to plan and construct the new facilities. We have already seen pictures of the running sheds opened in 1903 and the development of Campbell Road from around the same period. An article in the Railway Magazine in January 1903 made no secret that plans for the relocation from Nine Elms were well advanced. This picture shows the early construction of steel frames on a greenfield site. This picture was probably taken from the vicinity of what is now Campbell Road.

This picture shows a steel framework construction for the workshops at Eastleigh Locomotive Works, and at first sight, the erecting of a steel framed building appears to follow similar methods to those used to-day. When the picture is examined more closely, fifteen men can be seen working at high level. Today there would be extensive fall protection systems in place and safe systems of work to ensure safety is managed effectively. In this picture there are no safety measures to stop the workmen falling, not even rudimentary handrails or harness systems. The scaffolding, on even closer inspection, appears to be bamboo cane, tied together with straps and rope.

A report from November 1903 in the South Western Gazette advised that “good progress was being made at Eastleigh with the building operations connected with the new locomotive workshops there – the brickwork foundations for a large number of the columns to support the roof have been completed and many of the upright columns are now in position. The old running shed, coal stage etc. have been swept away.”

In this picture, the roof and external walls have been completed. Roof drainage has been installed and down pipes are protected by the steel support stanchions. The stanchions are fixed to concrete pads which protrude a few inches above the earth floor.

This picture illustrates the concrete pads supporting the stanchions and shows that the floor has been excavated for the installation of drainage. A rail track sits atop the earth floor on the left hand side of the picture and, again, it is assumed to have been a temporary track to permit construction materials to be brought in by wagon.

The bay is nearing completion. Timber flooring is in the process of being laid and stacks of timber awaiting installation can be seen in the foreground. A straight and level rail track runs through the centre of the building and there are inspection pits running along both sides of the workshop bay.

A handwritten caption on the back of the original photograph of this picture lists the names of the people, unfortunately the handwriting is indistinct and not all of the names can be deciphered. What is clear is the date, Saturday 11th May 1907, construction is well advanced.

This picture shows part of the erecting shop which we saw nearing completion. It shows how the building was used and the amount of work that was taking place only a short time after the works were opened.

(Picture courtesy of the John Alsop Collection)

(Picture courtesy of the John Alsop Collection)

The power house was the source of electricity supplies for the works, and this picture was taken in April 1910. P.K. Mann, a student at Portsmouth training College in 1930, as part of his studies, visited Eastleigh Locomotive Works twenty years later in 1930. In recording a tour of the power house he recorded that electricity was generated by steam power working electric accumulators in the power house. The gentlemen pictured are, to the right, Lieutenants Budden and Rhodes of the Royal Engineers, presumably acting as consultants for the new installations. The two railway mechanical drawing office staff to the left are Messrs Sharp and Urie. Robert Urie replaced Dugald Drummond as Chief Mechanical Engineer in 1912.

The power house is fully complete and pristine in this photograph, which was probably taken in 1910, and very much as P.K. Mann described it in notes from his visit in 1930.

Boocock and Stanton, writing in their book An Illustrated History of Eastleigh Locomotive Works, explain that the Works had an important place in British railway history as, partly opened in 1909, it was the last of the big workshops built by a major railway company for the construction and overhaul of its locomotives, and according to Dugald Drummond, it was considered to be the most complete and up to date works owned by any railway company at that time. Apart from raw material purchases, Eastleigh’s Locomotive Engineering Works was almost fully self-supporting during the steam era. Moving the work from Nine Elms in London enabled bigger and better locomotives to be constructed. The Locomotive Works at Eastleigh eventually produced 314 new steam locomotives and substantially re-built another 115, although its greater work volume was in the overhaul and repair of locomotives.

The first two engines to be built at Eastleigh were a pair of Drummond, S14 class 0-4-0T’s. The first engine to emerge, No. 101, is pictured at Eastleigh during September 1910. Only two of this class were ever built. The London and South Western Railway arranged for Locomotives to be painted in light grey for official photo’s as it created a better image using black and white photography. Once photographed the locomotive was returned to the paint shop to be re-painted in London & South Western livery.

(Picture courtesy of the Bradley Collection)

(Picture courtesy of the Bradley Collection)

To the side of the main Locomotive Works, alongside Campbell Road, were the buildings that housed the Forge, Foundries, Pattern Shop and Brickworks and a lot of “Hot” work took place in this area. It is not surprising that working with molten metal and large furnaces was separated physically from the main workshops for fire safety. The Forge block shown towards the left in this picture has a series of narrow chimneys behind the building. These were the chimneys from the boilers that fed the forge hammers which were located here. It is rumoured that the sound and vibration from these hammers could be heard and felt, not only in Campbell Road, but also other parts of the town.

Notes from the visit of P.K. Mann described the iron foundry in operation as a striking site to see when the castings were being made. It would also have been a very hot, dirty, and dusty environment to work in. Metal was put into cupolas, which were then heated in furnaces. When molten, the metal was transferred to ladles which were carried by overhead crane to the sand mould and then gently tipped. The molten metal was then poured to fill each mould, which was then left to cool before the hardened sand was broken away. The exposed casting was then left to cool further before being sent to the fettling shop to have moulding flashes and the risers (the channels in which the metal had been poured) cut off. The iron foundry occupied over half the length of the brick building that was shown in the earlier picture. The small track through the shop was for distributing components around the works in hand carts.

(Picture courtesy of the John Alsop collection)

(Picture courtesy of the John Alsop collection)

According to Mann, when the molten metal was poured into the mould sparks and molten metal would splash, so men in the foundry wore protective headwear and leather aprons when handling the molten metal. In this picture no metal is being poured, so aprons have been discarded. The floor in the foundry was covered with black sand which spilled when the mould was broken away from the casting.

Immediately behind the iron foundry was the pattern shop. A haven of peace, tranquillity and cleanliness compared to the foundry. The pattern shop was sandwiched between the iron foundry and brass foundry. Carpenters were employed to make the wooden patterns from which the moulds would be formed.

Notice in this, and the previous picture, the foreman’s office, at the far end, was elevated to give better surveillance of workshop activity.

(Picture courtesy of the John Alsop collection)

(Picture courtesy of the John Alsop collection)

The brass foundry, although smaller than the iron foundry, employed exactly the same techniques to produce the castings.

The brass foundry produced components such as slide valves, axle boxes and bearings.

(Picture courtesy of the John Alsop collection)

(Picture courtesy of the John Alsop collection)

Behind the brass foundry was the brick shop. Bricks were used to line the firebox of the locomotive’s boiler. The bricks in the firebox were there to protect the metal casing from heat damage and, as sacrificial items, required periodic replacement. In the 1930s, according to Mann, the clay bricks were dried in a large kiln which could accommodate 10,000 bricks and the kiln was fired twice a month.

Contrary to earlier comments about fire separation and locating “high risk” operations way from the main buildings, located within the main body of the Eastleigh Locomotive Works was the smiths shop and as you can see it accommodated long rows of small furnaces. There were also steam hammers for forging components such as valve and brake gear parts. The steam hammers in the smithy were far smaller than the larger three ton hammers across the yard in the forge where they produced larger items like connecting rods.

The noise from constant hammering and heat in the smith’s shop must have been oppressive, particularly as ventilation appears to be minimal. The atmosphere inside the shop would have been dusty and as can be seen in this picture the men working the furnace had to wear leather aprons and heavy duty boots for personal protection. A hardy bunch, some of the men also appear to be wearing waistcoats, but this is probably as additional personal protection against getting burnt rather than a sense of being fashion conscious.

Components from the foundry, forge and smiths’ shops progressed to the machine shops for completion. This picture of the brass machine shop is rich in detail, and it is clear how labour intensive the operations at the Locomotive Works were. The brass machine shop was a separate enclosure within the main machine shop and in this picture, you can make out the timber partition formed within the larger bay. All the workmen are wearing caps and ties. The machinists have their sleeves rolled up for safety, whilst the overhead lay shafts, flapping drive belts and unguarded machinery would today be considered a significant safety hazard.

The main machine shop was a large affair where ferrous metals were machined. The lathes pictured produced relatively small components and the narrow track running through the workshop was to carry parts to or from the workshops or stores by hand cart. This system was installed when the works were constructed and was copied from a system that had been employed successfully in the old works at Nine Elms.

As you can see in this picture some of the components were quite large and heavy. Overhead cranes could not work the length of the shop because of the series of lay shafts, belts and pulleys that were used to drive the machinery from high level, so local hoists would have been employed to lift the heavy items.

Steam railway locomotives were large beasts that sometimes required the machining of large components, using large machinery. A horizontal planer or milling machine can be seen on the right. I am not sure what the machines are along the left hand wall but it has been suggested that these may be machines for making ball bearings.

Again, more large machinery in the Machine shop. On the right there appears to be a large multiple workstation drill stand with at least six workstations.

Alongside the machine shop was the Wheel Shop. This picture, which probably dates from the early 1920s, shows wheel and journal lathes and a pile of tyres in the centre. The tyres were heated in gas rings and shrunk on to their wheel centres before being machined to size. This gave a wearing surface that could be readily replaced, rather than replace the complete wheel. This was exactly the same, in principle, to the practices that had been employed by wheelwrights over many centuries when fitting tyres to wheels for horse drawn carts and carriages.

According to the notes made by P.K.Mann, the wheels were forced onto the axle by hydraulic pressure and the overhead crane had a lifting capacity of thirty tons. On the left of the picture are some wheel turning lathes which are belt driven. Coupled wheels were turned on their axle as a matched set. According to his notes, as early as 1930, these wheel lathes had been converted to independent electric motor drive and were fitted with some form of automatic feed system so that they did not require constant manning. After machining the wheel sets would be balanced to minimise “hammer blow” to the track.

Components from the machine shop progressed to the fitting shop where they were put together to form sub-assemblies that would be installed into the locomotive. The fitting shop was conveniently located at the north end of the machine shop bay and adjacent to the stores and erecting shop.

The previous picture did not portray the number of people that worked at the benches. In this particular image of a small section of the shop, the men seem to be assembling liners into bearing blocks.

In this picture connecting rods can be seen laying across the benches.

When I was an apprentice, maintaining a clean and tidy workplace was one of the standards instilled in all trainees. Now I know why, but I must stress that this picture was not taken at Eastleigh.

One of the largest departments in the loco works was the boiler shop. Preparation for making boilers began in the boiler machine shop where steel sheeting was cut to size and pre-shaped.

In this picture you can see a heavy duty guillotine on the left, used for cutting the sheets of steel, whilst on the right are the machines that were used to roll and shape the plate to form the various sections of the boiler.

In this picture, the forming machines can be seen in closer detail.

Noise in the boiler shop was deafening and deafness was a consequence for many of the men who worked here. To construct a boiler, heavy steel sheeting had to be formed, riveted, and caulked to form a water tight and pressure tight compartment. This picture has been used in the book by Boocock and Stanton and is described as follows: “A pair of boilers have had all their firebox stays drilled out and the one on the right is having a new set of rivets applied around the back of the outer firebox wrapper. The riveter’s assistant uses a small coke hearth for heating rivets to red heat.” The red or white hot rivet, with the head formed at one end, would be pushed through a matching hole in the two plates to be joined. It would be held in position by a man pressing a dolly against the pre-formed head, whilst the other end was deformed by another man hammering to form a second head on the other end. Upon cooling, the rivet contracted and exerted further force, tightening, and sealing the joint.

This Cross feed water boiler in course of construction will eventually have to be tested before being built into the locomotive. When a boiler had been assembled it was filled with water and the water pressure raised to twice the nominal boiler pressure, so that any leaks could be identified and rectified. Once any repairs had been made, the fire was lit, and steam raised to a pressure 10% above nominal boiler pressure. Only when both tests had been successful completed was the boiler permitted to be installed in the loco.

As one of the largest items of the locomotive, the boiler was transferred to the erecting shop. In this picture the boiler has been fitted to the main frame and asbestos lagging is being wrapped around the boiler casing for insulation before the outer casing is fitted. We believe that this may be a Drummond D15 in course of construction. If so, this picture was taken during 1912, the year that they were built at Eastleigh.

This picture is believed to show a Drummond T14 during construction at Eastleigh in 1912. The smoke box housing and boiler casing have been fitted to the main frame and the cab is partially completed. The bogie frames, without wheels, are laying on the floor in the foreground.

With the major main frame construction completed this T14 locomotive body is about to be lowered onto the centre tracks in one of the erecting bays. No concern is apparent in the faces of the men in this photograph as many tons of machinery swing precariously above them. The hooks holding the frame have no nothing to hold them in position and are attached to chains. The crane hook has no retaining link and is also attached to a pulley chain. Remember the old phrase – “a chain is only as strong as its weakest link.” This phrase originated because when a chain failed, the weakness was not obvious, but the result was usually immediate and often catastrophic.

The final stage in preparing the locomotive for service was the paint shop. This loco has been finished in London and South Western Railway green with yellow piping.

To paint the loco, men had to access the high points by ladder and some examples of the ladders used can be seen leaning against the wall on the right. If I had been a painter in the loco works I wonder if the sight of all these loco’s lining up for attention would have been a welcoming sight? It must have seemed like a never ending conveyor belt.

When the locomotives first emerged pristine from the works at Eastleigh there is no doubt that each and every one of them were a magnificent sight and reflected the pride and passion of the community in which they had been built.

The construction of locomotives required teamwork and administrative operations were just as important to the success of the locomotive works as were the manufacturing operations. We have heard that Eastleigh Works was technically advanced for its day and able to produce virtually every component necessary to construct a locomotive. This was made possible by being able to purchase raw materials in a cost effective and timely manner. This is a picture of the purchasing office which was located in the stores. Those of you who are used to working in modern offices will notice the absence of technology, although the office had been provided with electric lighting, which was more than some of the workshops had been in the early days.

I apologise that these pictures of the stores have been “borrowed” from the internet but are worthy of recording as they reflect a time before computerisation and computerised stock control.

It is also interesting to observe that the stores were the only department to remain in their original location through the demise of steam locomotives in the mid-1960s and the transition to diesel locomotive and carriage work repairs following merger of the two works in 1967.

The building that dominated the front of the locomotive works was the administrative offices and this picture must have been taken in 1909 or 1910 when they had just been constructed. According to P.K. Mann, the accountant and his staff occupied the lower floor, together with the works manager and clerical staff, whilst on the upper floor were the engineer’s suite of rooms, the chief clerk’s office, draughtsman’s offices and those of the telegraph and telephone. Mann describes them as being built for use rather than ornament and consequently are by no means handsome to look upon, but they answer their purpose very well by being commodious, he recorded diplomatically. They, of course, still dominate the front of the site.

This is the layout of the Locomotive Works at Eastleigh from the days when it constructed steam locomotives and so far we have visited and viewed the activities in nearly every department, but there is more to come.

Photographers were fascinated with capturing images of the workmen at Eastleigh Locomotive Works spilling out of the premises for lunch or at the end of the day. It was a mass exodus that can be compared with the annual Wildebeest migration on the Masai Mara, only in Eastleigh it happened twice every day.

This is a picture taken from Campbell Road bridge looking up a Southampton Road towards the station. Those of us that lived in the area, even into the 1960s, knew the routine and at “chucking out time” at the Loco or Carriage Works, we knew to keep well clear of the commotion if we had any sense of self preservation.

With war being declared against Germany on the 3rd of September 1939, the engineering capability of the men working at Eastleigh was utilised for the war effort. These locomotives are Great Western Railway “Dean Goods” Locomotives, photographed with Eastleigh Works offices in the background. They have War Department markings and are numbered sequentially 181 to 184. It is probable that after being prepared at Eastleigh, they are being sent to continental Europe and may have seen service as far afield as the Middle East during WWII.

Nº 21C1 Channel Packet, designed by Southern Railways Chief Mechanical Engineer, Oliver Bulleid, who replaced Richard Maunsell on his retirement in 1937, caused quite a sensation when first unveiled to the public on 18th February 1941 with its innovative air-smoothed casing. Chanel Packet was the first of the “Merchant Navy” Class of locomotive and in this picture the then Minister of Transport, Lt.-Col. Moore Brabazon, attends the naming ceremony on 10th March 1941. he is inspecting the Southern Railway guard of honour consisting of men of the 4th Battalion, which became part of the 21st Hampshire Battalion, Home Guard at Eastleigh. In all, thirty of these locomotives were built at Eastleigh between 1941 and 1949, of which eleven have survived into preservation. Sadly, it is unlikely that many will ever steam again. It is believed that only three have been restored to working order, mainly because this class of Bulleid Pacific Locomotive is too large and heavy for use on most of today’s heritage railways.

This picture was taken on the steps that led from Campbell Road bridge to the timekeeper’s office in the locomotive works. It is a picture of B Troop, 71st (Hampshire and Isle of Wight) Heavy Anti-Aircraft Battery. Their Officer in Charge, Capt. West, is seated in the centre of the front row. This was the only Southern Railway unit to be trained for Heavy Ack-Ack duties with regular Army units. Together they manned anti-aircraft batteries around the Eastleigh district every night during WWII.

These pictures show a home Guard crew manning an Ack-Ack gun at Eastleigh. This gun would have afforded protection to the Locomotive Works and Carriage Works from its strategic location in the Carriage Works yard.

The book “Home Guard, Southern Railways” illustrates this picture with the caption – “When Major General G. le Q. Martel visited Eastleigh – and it was for long a secret that these important Southern Railway works did a tremendous amount of war work – the Southern Railway Home Guard paraded and were inspected by the great tank expert.” It perhaps does not illustrate the full story. When Don Welch entered the works as a young apprentice in the early 1940s, his abiding memory was not of locomotives, but of gun barrels stored everywhere. Eastleigh Loco works became a major armaments manufacturer during WWII.

During WWII, the Chairman of the Southern Region, Colonel Eric Gore Browne, as an old soldier, welcomed every opportunity of associating in Southern Home Guard activities. Here he is seen giving a critical eye to the 4th Battalion men at Bournemouth.

Sir Eric Gore Browne was given the privilege of meeting my father on 10th May 1948. The occasion was to present a new Rifle Challenge Shield, on behalf of the general managers of the former main line railway companies, to replace the trophy that had been destroyed by bombing in London during the war. It seems strange to-day, but prior to, during and after WWII competitive shooting was a popular sport practised between different divisions of railway operations. Sir Eric paid for the new trophy out of his own pocket and my father is accepting the trophy as Chairman of the Federation of Southern Railway Rifle Clubs.

To illustrate the popularity that shooting held at the time I have included this picture. It is of a group, of 17 members of the Southern Railway Rifle Club, led by my father as Chairman of the Southern Railway Rifle Club and the then Mayor of Eastleigh, Mr. T.W. Coles, on an official Civic visit to St. Hellier on the island of Jersey in January 1947. I understand that this was the first official Civic visit to Jersey from the British mainland since the island had been occupied during WWII. I have the original newspapers that recorded the event and it made front page headlines for two consecutive days.

A competition had been organised between the railway team and a Jersey team. My father was judged to have missed the target bottom left with one of his shots. He joked that a man of his calibre could not possibly miss the target, and somebody took him seriously. On re-inspection it was discovered that due to ovality, two bullets had penetrated the same hole. The scorecard was amended and signed by the dignitaries present as my father had shot a perfect score, a bit like a golfer getting a hole-in-one and on an official occasion.

In post war austerity and tranquillity, it seemed like the age of steam would last forever. This picture, taken in the early 1950s from Campbell Road bridge, looking towards Eastleigh station, shows N15, 30783 Sir Gillemere, hauling freight wagons, heading for Southampton. A woman on the bridge looks on whilst pushing her pram and a bus manoeuvres the slope as it threads its way between pedestrian and cyclists.

Railway open days were a major event in the social calendar in Eastleigh and this picture was probably taken around 1950. The first of Bulleid’s Merchant Navy Class, Channel Packet, is pictured, surrounded by children of all ages wanting to stand in the cab and pretend for a few moments that they were engine drivers. This picture shows the locomotive in original, as built condition, without smoke deflectors fitted to the front side casing. You can see why, with food in short supply and many tinned meat products imported, that these locomotives were nicknamed “Spam Cans”. From 1956, this class of locomotive was re-built at Eastleigh, with the air smoothed casing removed.

Another of Oliver Bulleid’s innovative designs from the WWII period was this rather unusual looking 0-6-0 class Q1 Austerity locomotive. These locomotives were introduced in 1942 and under wartime austerity, materials were in short supply, hence all superfluous features were stripped away. This Locomotive became the most powerful 0-6-0 steam locomotive ever to run on Britain’s railways. They were nicknamed “Coffee Pots” and the first of the class, C1, has been preserved and now resides at the National Railway Museum in York. One aspect of their shape was that, like Bulleid’s Battle of Britain Class, pictured behind it, they could be simply driven through a coach-washer for cleaning at a time when manpower for this time-consuming chore could not be spared. These locomotives were built at the Brighton and Ashford works but have an important place in the history of steam. None of this mattered to the kids wanting to clamber on-board at Eastleigh. Railway open days did however matter to many children of railway employees who had been orphaned. The proceeds from Works open days went to support Woking Homes. This organisation, opened in 1896 as a shelter for girls who had lost their fathers and whose mothers needed to go to work. The charity became known as the London & South Western Railway Servants Orphanage when new premises were built at Woking in 1909 and accommodated both boys and girls. The charity continued to be supported by donations from railway employees and fund raising events until the orphanage was closed in 1988.

Children of all ages enjoyed a visit on the footplate of a steam locomotive as this picture of dignitaries on an official visit to view 21C6 Peninsular & Oriental Steam Navigation Company illustrates. A driver and fireman, in appropriate flat caps, as befitting their station, are on hand to answer questions. This locomotive was built at Eastleigh in December 1941 and although the first two members of the Merchant Navy class had their air-smoothed casings made of sheet steel, 21C6 was one of eight in which the casing was made of asbestos board, with a visible horizontal fixing strip along the centre line, which can be seen in the top right of the picture. Seen as a technologically advanced material at the time, asbestos became recognised as a material hazardous to health, but not before it had cast a shadow over many workmen and their families in the town.

As a young child growing up in the 1950s, going to the Eastleigh Carnival was a magical experience and never was the rivalry between the Carriage Works and Loco Works more intense. Floats were entered by individual workshops, not the works themselves and in the interest of fair competition, workers from each department, in each works, had to select their theme and construct their floats and costumes in their own time, but who said things were fair! No foreman would want to prevent his department from being awarded a coveted “First Prize” which could be hung in his office as gloating rights for the following year. So, in the weeks leading up to the carnival there was a lot of activity in both works, but not all to the benefit of the company. These pictures are of displays entered by Eastleigh Carriage Works Body Shop in the 1950s. The picture of the “Household Cavalry” shows skirts below the horses which were intended to disguise the legs of the riders. Holding down a bit of skirt did not come naturally to the lads, but they overcame their dilemma by sewing metal washers around the hem. They were not good seamstresses. By the time they had marched to Passfield Avenue, most of the washers had fallen off. The Wagenham Girl Pipers was a parody on the act, The Dagenham Girl Pipers, who were a very popular marching band of the time and the lads had to flex their muscles as part of the “Chain Gang” when they carried this “Steel Girder”. Realistic as it appears, the “girder” was constructed in plywood, but it felt like the real thing by the time they had finished. In those days the carnival procession could stretch to over a mile long as it wound its way through the streets of the town.

The last mainline steam locomotives produced by the Southern Railway were the Oliver Bulleid, West Country and Battle of Britain Class. Lighter but similar in appearance to the earlier Merchant Navy class, these locomotives with their air-smoothed casing were also, like the larger Merchant Navy class, referred to as “spam cans”. The first of the class, 21C101 – Exeter, emerged from Brighton Works in May 1945. In all a total of 110 West Country and Battle of Britain locomotives were constructed between 1945 and 1950, with six of the last batch being built at Eastleigh. This picture of 21C101 now renumbered 34001 by British Rail and with air-smooth casing removed, was taken at Eastleigh following an overhaul and refurbishment in the late 1950s. It is from my family album and the driver is my father-in-law, Harry Chamberlain, who was born and raised in Campbell Road. He was the son of the Harry Chamberlain we saw in the picture at Eastleigh sheds with the “A12” loco in the early 1900s. The significance of the picture was that “Exeter” was the original family home and there were still relatives living there. He was a second generation driver from the same family living in Eastleigh, this was not uncommon in the 1950s. My father-in-law, Harry, having left school at 14 started a job with Pirelli. A few days before his 16th birthday his father told him to hand in his notice, he had arranged a job for him on the railway, starting Monday. The railway in Eastleigh had heralded a period when working for the railway was a “job for life” and jobs were, more often than not, handed down through the family line.

Twenty of the West Country and Battle of Britain Class locomotives still exist in varying states of preservation. Not all the locomotives were rebuilt without the air-smoothed casing and ten in original condition and ten rebuilds remain. It is unlikely that all of the preserved locomotives will be restored to working order. The last steam locomotive built at Eastleigh 34104 “Bere Alston”, which was built in April 1950, was the last locomotive re-built here in May 1961, hence this formal picture was taken to record the event.

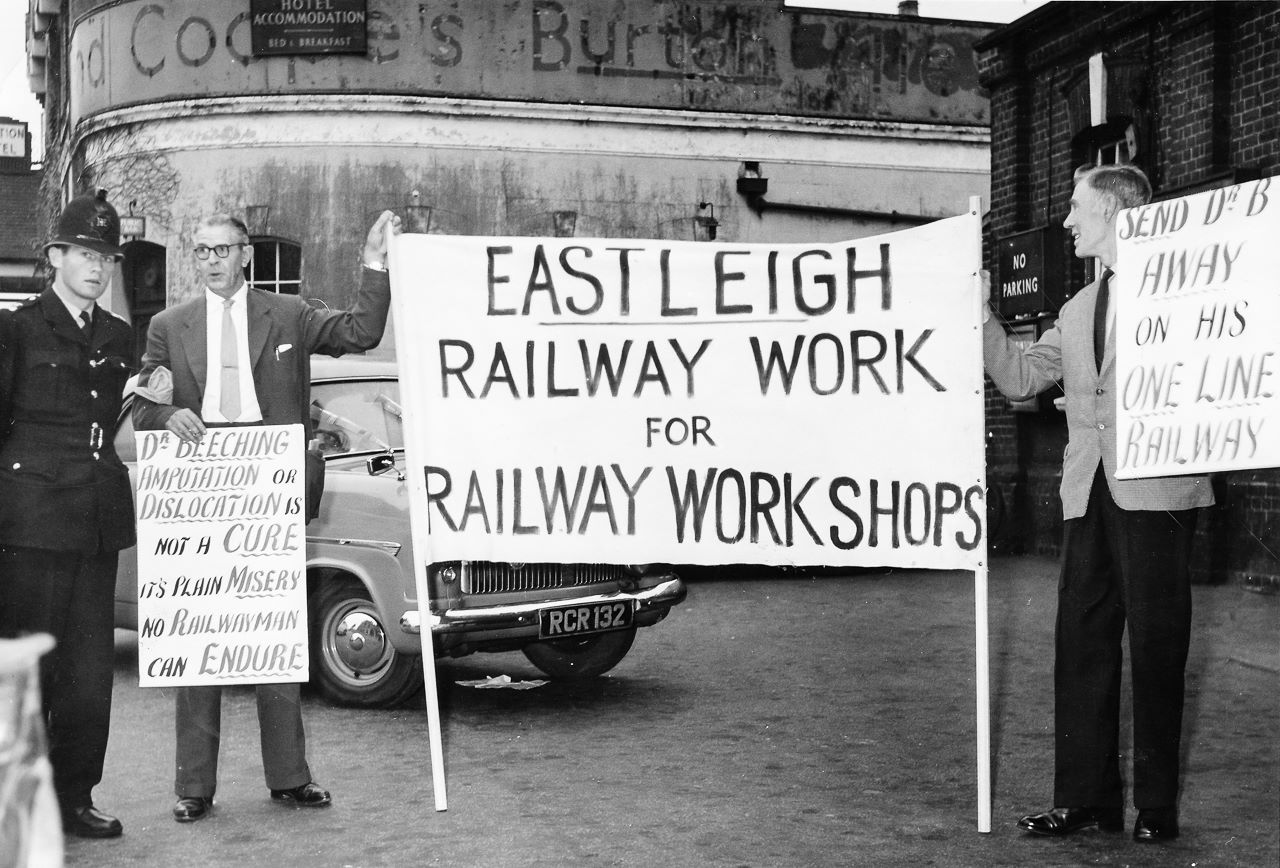

By 1961 clouds of uncertainty began to hover over the railway nation-wide as running costs escalated and successive Governments tried to find a solution to all networks haemorrhaging money. The rail network was losing the equivalent of £5 million pounds a day, at present day values. The name Beeching was not popular in these parts and only history will determine whether he was the saviour or destroyer of the railway. It is not my intention to explore this further, although we do need to look at what effect his recommendations had on Eastleigh. The decision had been taken in 1955 to phase out steam locomotives and replace them with more efficient and more cost effective diesel and electric locomotives. Despite huge levels of investment, transition up to the early 60s was slow and losses were escalating. Under Beeching the programme to eliminate steam was accelerated, amid many other changes and, by the end of 1966, there were few steam engines left that would require maintenance. More importantly, the need for facilities at both Eastleigh Carriage Works and Eastleigh Locomotive Works, was brought into question. The Southern Region abandoned steam working on all its lines in July 1967.

With plans to replace steam locomotives it was decided in 1962 that the Locomotive Works would not be needed beyond late 1966. Eastleigh Carriage Works had been built in 1890 and originally designed to build relatively short, timber framed carriages. This meant that buildings were relatively short, and stock had to be moved by traversers between adjacent workshops. This did not match well with the needs to develop a more streamlined and efficient production process for carriage construction and maintenance for the more modern and longer coaches. The decision was made, and plans developed to close the Carriage and Wagon Works and transfer the work and workforce to the modified Locomotive Works. Although many of the buildings are still standing, the Carriage Works, the creation of which gave rise to the town of Eastleigh, was closed after being in operation for only 77 years.

Some job losses and re-training were inevitable, and for a time there was much gnashing and wailing at the demise of the Carriage Works, but no Government of any persuasion was going to stand in the way of the cost savings that had to be achieved. As early as 1962, the works at Eastleigh had taken over the whole of the Southern Regions repair work on steam, diesel, and electric locomotives as well as motors from multiple unit stock. The reality was that new diesel/electric locomotives and rolling stock required far less maintenance and repair than their predecessors. Even so, many of the employees from the Carriage Works were transferred to join their “old rivals” at the Locomotive Works in 1967. When transfer was completed in 1968 there were still over 2,500 people employed in the new works.

The transition from building steam locomotives to repairing carriages and diesel/electric locomotives was carefully and, from a manufacturing viewpoint, well-conceived. The old locomotive works building was far longer than any of the buildings in the old carriage works. The main bay of the old erecting shop was transformed to accommodate progressive working, so carriages could enter at the back and pass through the various stages, emerging at the front into the works yard. The transformation of the old loco works also introduced new initiatives. British Rail diversified into building shipping containers, after all, they had all the necessary metal bashing skills available in house and, most importantly, transporting containers by rail had the potential to be a lucrative business, particularly from Southampton Docks (owned by British Rail) to London and the major cities of the Midlands. A new Apprentice Training School had been established on the site in the late 1950s. Apprentice training had always played a big part in the operations of both works and, in particular, at this time it was important to train young people in the new technologies and skills that would be needed for a successful future.

The new Works training school had been developed to instruct boys of school leaving age, which was then15, although apprenticeship to a particular trade, in either of the two Works in Eastleigh would not commence until they had reached 16. The training school had an annual intake of 50 boys a year.

The boys in each new intake were assessed by their instructors as to their aptitude and then placed in the training section best suited to their abilities. An apprenticeship on the railway was a prestigious position and, at the time, was believed to be offering the opportunity of a career for life. Above the workshops there were classrooms for theoretical training. The Training School became very successful and other organisations in the town used these facilities for their own apprentice training. Although I was indentured as an apprentice to Pirelli General, I was given day release to Eastleigh Technical College and attended lessons in this building in the mid-1960s.

We tend to associate diesel and electric locomotives as a product of the 1960s, but Eastleigh Carriage Works were building Electric Coach Units as early as 1937. A visit by the Chairman of the Transport Commission, Sir Brian Robertson in July 1959 included inspection of the Diesel Engine Repair Shop at the locomotive Works and a review of the Diesel Electric Multiple Unit Shed which had been built adjacent to the Motive Power Depot in Campbell Road. In 1962 this Diesel Engine Testing Bay was constructed at the back of the Locomotive Works and opened in September 1963.

To many, the locomotive Works at Eastleigh represented the age of steam, however, the pictures we are now going to show are from a series taken during 1963. This Testing Bay was constructed so that Locomotive performance could be measured before the locomotives were released for duty. The Test House provided a better controlled environment than the side of an open track to test the engine to full load. It may to some of you seem impossible, but this picture was taken over 50 years ago, and the locomotives pictured in the new Test Bay, like their steam counterparts, are now considered museum pieces. The locomotive pictured No D6529, was one of 98, Class 33s, built by the Birmingham Railway Carriage and Wagon Company for the Southern Region of British Railways between 1960 and 1962. They were known as “Cromptons” after the Crompton Parkinson electrical equipment installed in them. Twenty Nine examples have been preserved, D6529 is not one of them. The other Locomotive is a class 08 Diesel-Electric shunting locomotive. These shunters were produced between1952 and 1962 and a total of 996 were built making them the most numerous of all British locomotive Classes constructed, sadly none of these were made at Eastleigh. Over 60 of these locomotives have been preserved or are still operational.

In 1959, Eastleigh Locomotive Works were able to accommodate complete top and general overhaul services for diesel engines. The Diesel Building had been built to the south eastern end of No 1 and 2 bays of the erecting and boiler shops and partitioned off from the rest of the works to exclude, as far as practicable, the dirt, dust and fumes, inseparable from steam locomotive repairs, which were still being undertaken.

In this picture work is taking place on a top overhaul repair to Type 3, 1550 Horse Power Sulzer Engines. This was the engine fitted to the Class 33 locomotive that we saw in the test bay picture. When I saw these pictures for the first time, I was surprised as to how large the engines were. Presumably, other than a small space at either end of the Loco for the driver’s cab, the rest of the loco body accommodated the engine and generator. Fuel tanks were located under the chassis. It is strange, but because it was visible you were aware of how much fuel was needed for a steam locomotive, but not for a diesel.

These are pictures of diesel engines from Southern Region diesel electric multiple units and diesel electric shunting locomotives under repair in September 1963. Notice how clean the working conditions are compared with the pictures we saw earlier showing the early days of steam locomotive construction.

Cleaner conditions were needed for repair and maintenance of the fuel related elements of the engines. This picture shows the high technology fuel pump and injector test rooms. There were four air-conditioned rooms for repair of turbo-chargers, fuel pumps and injectors. Equipment in these rooms included: Fuel pump test bench; Injector nozzle re-conditioning machine; Cleaning cabinet and Testing machine. The picture to the right shows fuel pump repairs being undertaken in the Injector repair room.

Clean conditions were also paramount in the Electrical Repair shop as this picture illustrates. During a visit by the British Transport Commission Chairman, this shop was in course of re-organisation to enable repair and overhaul of electrical apparatus which was being introduced. The shop was established to deal with all repair work allied to diesel engine-generator sets in addition to the traction motors of multiple electric stock.

Armature re-winding was an operation carried out in the shop. In the picture on the left, an English Electric 507 motor armature is undergoing a re-build. In the picture on the right, wedges are being fitted to an English Electric 507 armature.

As with diesel engines, full tests were carried out on electric motors to ensure that the locomotive would not “fail” when it entered service.

One of the 29 Class 33 Diesel Electric Locomotives under preservation, D6508 was renumbered 33008 and named “Eastleigh”. With the creation of British Railways Workshops in 1962, Eastleigh Works ceased to be directly managed by the Southern Region. In 1973, British Rail Engineering Ltd (BREL) was formed with its own structure and board of directors which reported to the British Railway Board. By the early 1980s, the British Railways Board, realising that one of its major expenditures was in the overhaul and maintenance of traction and rolling stock, instigated a Manufacturing and Maintenance Policy Review, which was completed in 1986. This review had recommended significant changes to the way that operations had been carried out and that new vehicle building, heavy overhaul and component repairs would be put out to competitive tender. In 1988 BREL was divided into two companies and Eastleigh Works came under the banner of British Rail Maintenance Ltd (BRML). This structural re-organisation was done with the long term aim to prepare sites like Eastleigh Works for future sale to the private sector. Eastleigh Works now focussed on the local rolling stock market with Network South East as the key customer. As multiple units gained sway on most services, the visits of locomotives for traditional overhauls became even rarer.

Eastleigh Works entered the private sector as Wessex Traincare Ltd through a management buyout in June 1995. G.E.C.– Alstom bought Wessex Traincare in February 1998 and before the end of the year announced major redundancies. Alstom failed to gain contracts for new trains to replace aging rolling stock and in mid-December 2004, Alstrom announced that the Eastleigh Works would be closed. The site was finally closed in March 2006. The site is now owned by St Modwen Properties, a property development company and in 2007 Knights Rail Services began operations on site to store off-lease rolling stock. Arlington Fleet Services acquired the lease from Knights Rail in 2013 and now manage the site. Parts of the site are sub-let to South West Trains, Siemens Rail Systems and Colas Rail who, together with Arlington, carry out repairs, refurbishment and overhaul operations to current locomotives and rolling stock. The site now employs in the region of 160 people.

The man who inspired the London and South Western Railway to establish Bishopstoke as the centre for railway construction and maintenance operations was the Honourable Ralph Heneage Dutton. His vision and leadership gave rise to the town of Eastleigh. The development of the town was strongly influenced by the railway company with many grand Victorian buildings standing majestically to display how successful the town had become. The town soon attracted other large factories to the area. To-day most of the grand buildings have been demolished and the large industrial operations which once employed thousands of workers no longer exist. To paraphrase my colleague, Bob Winkworth, in his book – “Eastleigh, The Railway – The Town – The People.” Eastleigh was once both a proud railway town and an area of individual character. A period of time in which, over a few short decades, character, interest, and industry flourished. The Carriage Works, the initial development that kick started the development of the town, closed after 77 years. The site has been turned into an industrial estate comprising warehousing, manufacturing, vehicle maintenance and leisure facilities. This site now employs a small fraction of the people that once worked there. The Locomotive Works, which opened in 1909 were closed in 2006, just short of a century in operation. The works are still standing and maintenance operations to rolling stock are still undertaken from the site, although the number of people employed is small compared to the numbers that were employed in its heyday. Diesel and electric locomotives were more efficient than steam locomotives but did not create the same passion, did not require the high frequency maintenance that steam demanded and, as a result, Eastleigh Works gradually declined and was closed because it was not economically viable.

William Panter Ralph Heneage Dutton Dugald Drummond

William Panter Ralph Heneage Dutton Dugald Drummond

Robert Wallace Urie Richard Edward Lloyd Maunsell Oliver Vaughn Snell Bulleid

To me, growing up in the era of steam, these are the men that made Eastleigh famous, yet they are just a distant memory and their role and the role of the railway in creating the town are no longer understood, recognised, or commemorated by the people that live here. I wonder what these illustrious men would have thought about the decision that new locomotives and rolling stock for the railways of Britain are being designed and built in Germany and Japan. I leave you to form your own opinion.

Built in Eastleigh. A pictorial outline of more Locomotives that can be associated with the Locomotive Works at Eastleigh.

This M7 tank locomotive was the first design by Dugald Drummond upon replacing William Adams as Locomotive Superintendent of the London and South Western Railway in 1895. Notice as an official picture, the loco has been specially painted in light grey and that the background has been etched out to highlight the profile. The first 25 were constructed at Nine Elms Locomotive Works between March and November 1897, a total of 105 of this class of Loco were constructed, with the last 10 being built at Eastleigh in 1911. By the end of 1963 those that remained were based at Bournemouth to work the Swanage branch line. Two have been preserved.

This London and South Western Railway Class T14 was one of ten 4-6-0 locomotives designed by Dugald Drummond for express passenger use which were built at Eastleigh between 1911 and 1912. The T14 s were the most successful of Drummond’s 4-6-0 designs, although they were heavy coal and water consumers on a railway that did not employ water troughs, which combined with a high frequency of hot axle boxes, did not endear them to their crews. They continued into public ownership of British Rail in 1948. However, they began to be withdrawn from November 1948, with the last one surviving until June 1951. None have been preserved.

This D15 class 4-4-0 was the last steam locomotive design by Dugald Drummond in 1912. This particular Locomotive emerged from Eastleigh Works in February 1912 and was the first of his D15 class. Dugald Drummond died in November 1912. Number 463 was fitted with a hooter rather than a whistle, which it kept until the Second World War. The class continued into British Railways service in 1948 but were gradually withdrawn in the early 1950s. None have survived.

This is a Drummond 4-6-0 Class E14 and although Drummond had been given authorisation to build five, this was the only E14 class locomotive to be built and it was built at Eastleigh. The poor quality of the E14’s original design was highlighted by the fact that it had been earmarked by Drummond, after its initial release, for major modifications in the light of poor operational performance. Drummond died before this could be undertaken, and it fell to his successor, Robert Urie, to undertake the modifications. However, Urie decided to rebuild the locomotive as the eleventh member of his H15 class in 1914. This locomotive had a high coal consumption and as a result of its poor performance, gained the unenviable nickname of the “Turkey.”

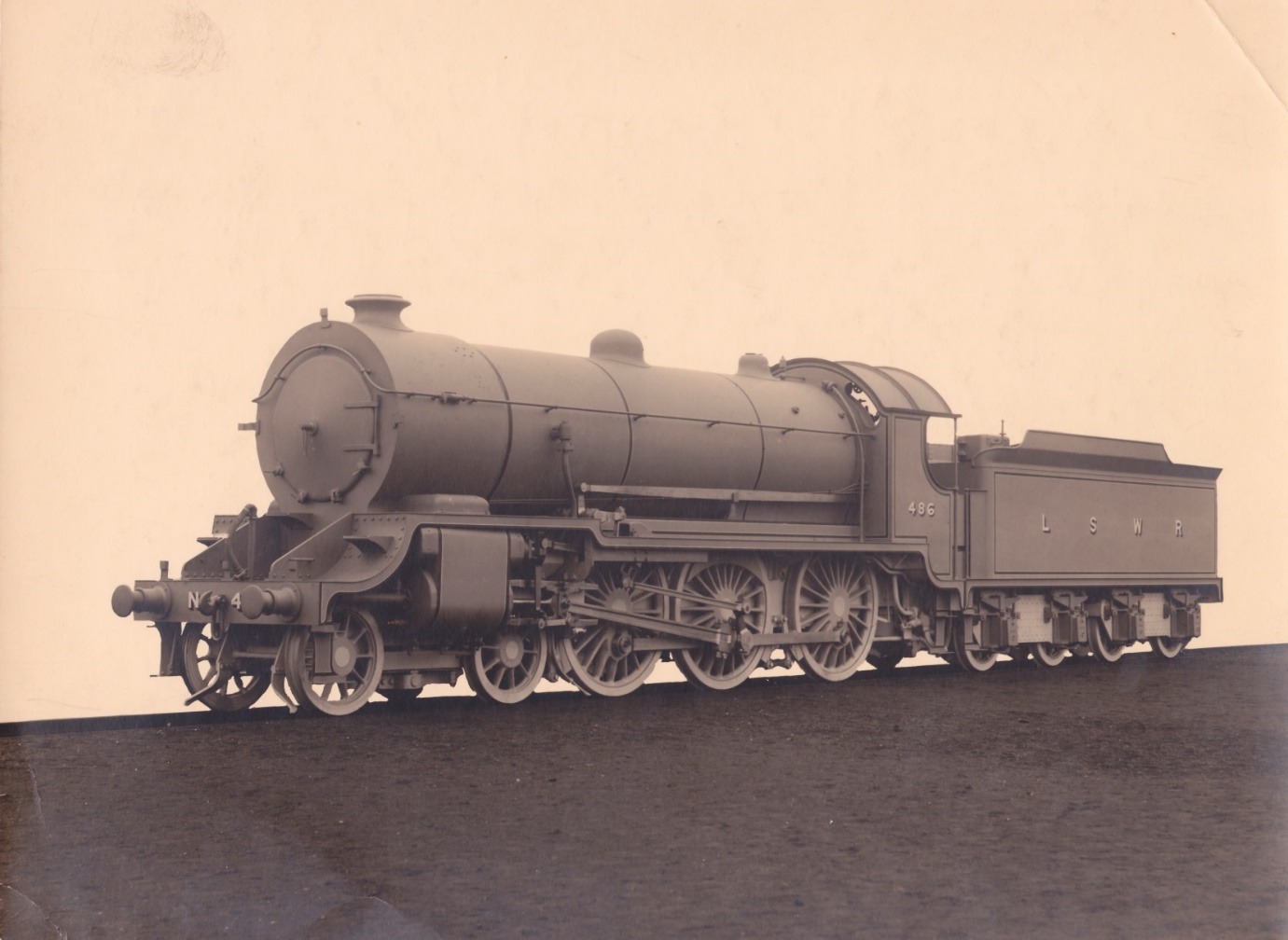

The H15 class was a 2-cylinder 4-6-0 steam locomotives designed by Robert Urie for mixed-traffic duties on the London & South Western Railway. This H15 class represented Robert Urie’s first design. It was created in response to a desperate lack of adequate locomotives that could be utilised for heavy freight duties. Ten locomotives (numbers 482–491) were built by Eastleigh Works between January and July 1914. A total of 26 locomotives were completed in six batches, over a period of twelve years. A further fifteen locomotives were constructed in three consecutive batches during 1924, the final one appearing in January 1925. All members of the class had been withdrawn by 1961 as a result of the British Railways 1955 modernisation plan and no locomotive has survived into preservation.

This S15 class was a British 2-cylinder 4-6-0 freight steam locomotive designed by Robert W. Urie, based on his H15 class and N15 class locomotives. The class had a complex build history, spanning several years of construction from 1920 to 1936. Following the grouping of railway companies in 1923, the London and South Western Railway became part of Southern Railway and the Chief Mechanical Engineer of the newly formed company, Richard Maunsell, increased the S15 class strength to 45 locomotives. The new locomotives were built in three batches at Eastleigh and were in service with the Southern Railway for 14 years. The locomotives continued in operation with the Southern Region of British Railways until 1966. Seven examples have been preserved for use on heritage railways and are currently in varying states of repair and restoration. The locomotive pictured, no 825, is preserved and was operating on the North Yorkshire Moors Railway until the summer of 2013 when it was withdrawn from service to undergo major repairs. Locomotive No 828 was purchased by Eastleigh Railway Preservation Society in 1980 and restored at Eastleigh Works where it had been built in July 1927. Loco no 828 operates at the Mid Hants Railway, Alresford.

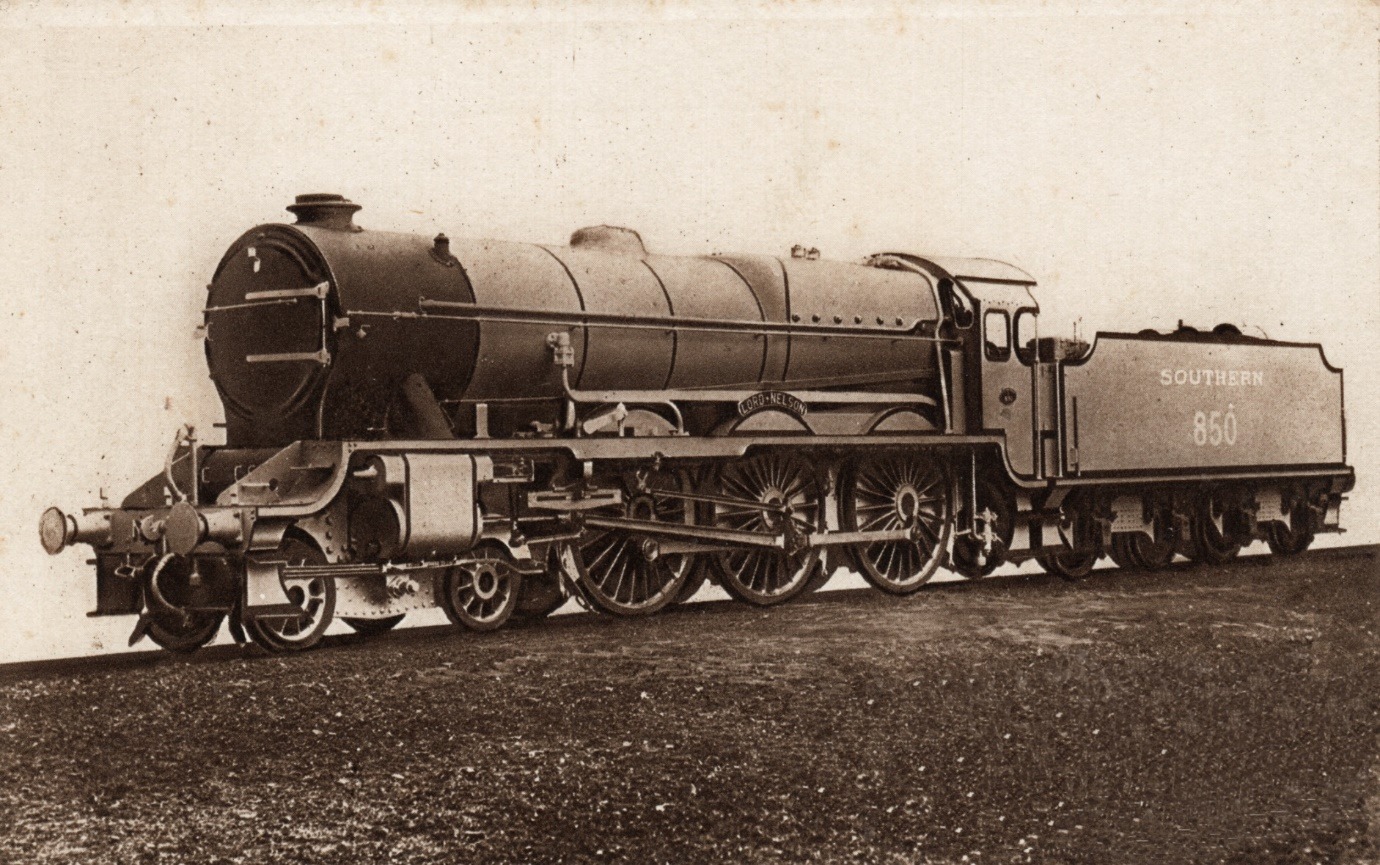

The Lord Nelson Class of 4-6-0 locomotives was designed by Richard Maunsell. The prototype was ordered from Eastleigh works in June 1925 but because of design changes during construction to reduce weight the locomotive did not appear until August 1926. All sixteen locomotives of this class were all built at Eastleigh and named after Royal Navy Admirals. Originally designed to haul Continental boat trains between London and Dover, they were later used for express passenger work to the South-West of England. When first introduced the performance of these locomotives was mixed, depending upon the experience of the crew and the circumstances under which they were operating. Maunsell undertook a number of experiments to improve performance and the class benefitted from the fitting of smoke deflectors in the late 1920s. A further batch of ten locomotives was ordered in 1928, but the Stock Market Crash of 1929 reduced the demand for continental travel and the order was reduced to five. Their performance was transformed by modifications introduced by Oliver Bulleid in 1938. The entire class was withdrawn from service during 1961 and 1962, having been superseded by Oliver Bulleids Pacific Locomotives. The only survivor, first-of-class No 850 Lord Nelson, (pictured) has been preserved as part of the National Collection.

The School’s class, is a class of steam locomotive also designed by Richard Maunsell for the Southern Railway. The class was a cut down version of his Lord Nelson class but also incorporated components from Urie and Maunsell’s King Arthur class. It was the last locomotive in Britain to be designed with a 4-4-0 wheel arrangement and was the most powerful class of 4-4-0 ever produced in Europe. All 40 of the class were named after English public schools and were designed as an intermediate express passenger locomotive. 40 were built in Eastleigh works between 1930 and 1935. Three examples are now preserved on heritage railways. Where possible, the Southern sent the newly constructed locomotive to a station near the school, after which it was named for its official naming ceremony. Pupils from the school were encouraged to view the cab of “their” engine. A good bit of public relations and marketing and, it worked. The name of the locomotive pictured is Whitgift. Whitgift School is a British independent day and boarding school in South Croydon, London.

The N15X class or Remembrance class were a design of 4-6-0 steam locomotives converted in 1934 by Richard Maunsell of the Southern Railway from the London Brighton & South Coast Railway L class 4-6-4 locomotives that had become redundant on the London to Brighton line following electrification. All seven of the L.B. Billinton designed L Class locomotives entered Eastleigh works in 1934 for rebuilding, each leaving the works the same year. The locomotives were named after famous Victorian engineers except for Remembrance, which was the London Brighton & South Coast Railway’s memorial locomotive for staff members who died in the First World War. The rebuilt locos weren’t popular with the crews, all being withdrawn by 1957, none have survived.

This picture is of an Adams 330 class saddle tank no 335 in front of the erecting shops at Eastleigh Works. The London and South Western Railway 330 class or Saddlebacks, as they were known, was a class of goods 0-6-0 locomotives designed by William Adams. Twenty were constructed between 1876 and 1882. All passed to the Southern Railway at the grouping in 1923. Withdrawals started the following year, and by the end of 1930, only five remained. It is probable that this picture was taken some time in the late 1920s as the engines carry “Southern Railway” markings. All locos of this class had been withdrawn from service by 1933 and scrapped.

Bibliography

Drewitt, Arthur (1935) Eastleigh’s Yesterdays, The Eastleigh Printing Works

James, Charles E (1972). Eastleigh & District History Society – Occasional Paper No 7 – The Junction Hotel

Bowie, Gavin G.S. (1986) Eastleigh, Bishopstoke and Chandlers Ford in Old Picture Postcards, European Library.

Brown, George J. (1986) – Eastleigh Our Town, Golden Jubilee 1936 to 1986, Boyatt Wood Press.

Norris, Norman (1986) – Eastleigh, An Illustrated History of the Council 1895 to 1986, Milestone Publications.

Robertson, Kevin, (1987) – The Last Days of Steam in Hampshire, Alan Sutton Publishing Ltd.

Robertson, Kevin (1989) – Hampshire Railways in old photographs, Sutton Publishing Ltd.

Brown, George J. (1991) – Eastleigh Railway Institute Centenary 1881 – 1991, Boyatt Wood Press.

Robertson, Kevin, (1992) – Eastleigh – A Railway Town, Hampshire Books.

Cox, Gordon Daubney, (1996) Eastleigh, The Chalford Publishing Company.

Eagles, Barry J., (2002) – Eastleigh – Steam Centre of the South Western, Kingfisher Productions.

Boocock, C. & Stanton, P. (2006) – An Illustrated History of Eastleigh Locomotive Works – Ian Allan Publishing.

Winkworth, R. (2007) Eastleigh, The Railway – The Town – The People, Noodle Books.

Additional Material

Arlington Fleet Services Ltd., South Western Circle, Joan Simmonds, Melvin Hellard, Bob Winkworth, Roy Smith, Gil and Julia Broom, Arthur Knott, Fred Betts, Denis Holdaway, Don Welch.