Research by Joan Simmonds/Chris Humby Compiled by Chris Humby (from a talk first presented in June 2012)

A review of the history of schools in Bishopstoke and how events at these schools related with what was happening in education nationally.

Education as we know it today was a product of the Victorian era. The earliest schools in England, at least, those we know anything about, date from the arrival of Christianity around the end of the sixth century. The object of these early schools, attached to cathedrals and to monasteries, was to train priests and monks to conduct and understand the services of the Church, and to read the Bible and the writings of the Christian fathers.

The industrial revolution of the 18th and 19th centuries highlighted the problems of a society that was not educated. Alongside the upheaval of industrialisation, the process of democracy also got under way with the Reform Act of 1832. This gave a million men the right to vote and created social pressure to provide better education. To provide for England’s newly industrialised and enfranchised society, various types of school began to be established, to offer some basic education to the masses. It is difficult for us to imagine today, but many workers in Victorian England were children and throughout the 19th century more than a third of the population of England and Wales consisted of children aged fourteen or less.

In the once leafy lanes of Bishopstoke, children from poor families were expected to go to work from a young age, sometimes as young as 5 or 6 years old. Occasionally a Sunday School, during their only free time of the week, would offer a little education.

By the early 1800s, the Church regarded education for all children as desirable. The National Society was founded in 1811 by the Church of England. Its aim was to provide a school in every parish. The inclusion of the fourth “R” of religion, alongside the other three (reading, writing and ‘rithmetic), was simply assumed as right. By 1840, the School Sites Act, encouraged local gentry and clergy to provide schools for the masses, although schooling was not compulsory, nor free.

In the early 1800s, the idea of education for the poor was widely opposed as a matter of principle, other than to instil moral guidance. There were also differences of opinion between those who wanted children in school and those who wanted children at work. Child labour and school attendance were inter-linked problems and there was opposition to schooling from both parents and employers.

Despite the hostility to universal education, new schools were being built and school attendance was rising. By 1835, the average time a child spent at school was just one year. The first purpose-built school in Bishopstoke was built in 1842, for the sum of £600.

This school, which no longer exists, was sited near the junction of Alan Drayton Way, Fair Oak Road, and Manor Road, close to where D.G. Supplies stands today. By 1851, the average length of school attendance, nationally, had risen to two years. In 1861, most children received some form of schooling, ‘though still of very mixed quality and with the majority leaving before they were eleven’.

The National School in Bishopstoke was the only one in the parish and, as you can see from this map of Bishopstoke Manor, the parish was far larger than the Bishopstoke we know today.

The typical school day for much of the Victorian period lasted six hours. The morning session ran from 9 a.m. to 12 noon, when there was a break for two hours, necessary because most children had to walk back to their homes for a meal. The afternoon session commenced at 2 p.m. and ran until 5 p.m. As well as the outlying farming districts, the National School in Bishopstoke, as late as 1868, also catered for children living in North Stoneham, Barton, and the area around the railway station in what was to become known as Eastleigh.

Children travelled to school on foot, in all weathers, on roads and paths that were unmade, unlit, muddy, and puddled in wet weather. Many of the children in the parish would not have had decent clothing to protect them from the elements, some would not even have had boots or shoes as their parents could not afford them. There are records in the Bishopstoke school log from 1865 that some pupils were given leave to attend a soup kitchen (we don’t know where). There are also records that, the then Rector of Bishopstoke, Dean Garnier, organised the distribution of clothing to the poor of the parish. Lack of suitable clothing, and particularly boots, to attend school in was another cause of non-attendance. In 1865, it is recorded that a Frederick Savage was withdrawn from Bishopstoke school because it was too far for him to walk.

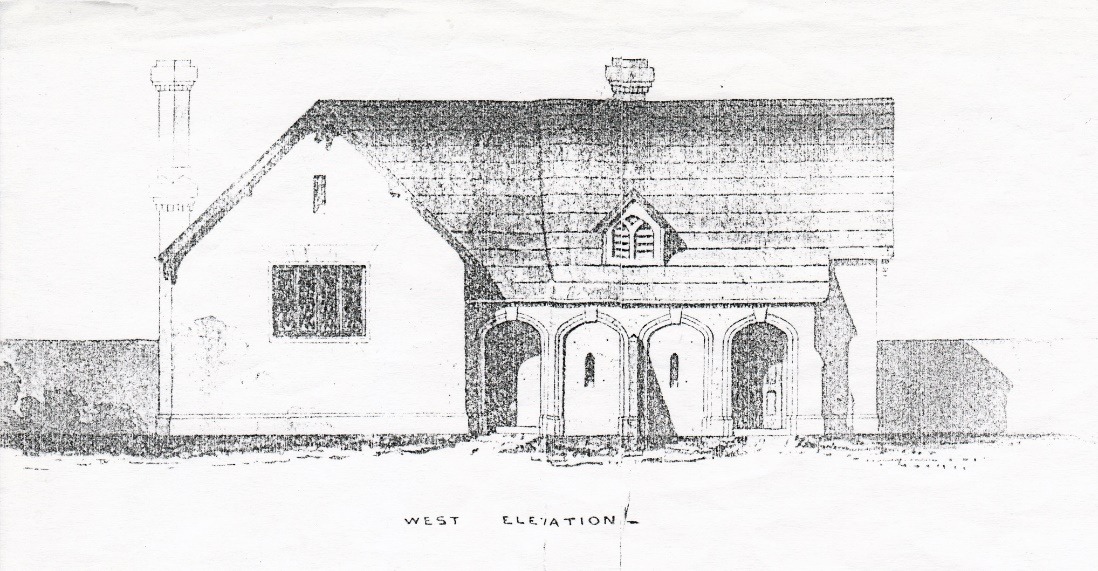

We are fortunate to have obtained layouts designed by a Southampton architect, for Bishopstoke National school and the schoolmaster’s house, which were built in 1842. The layout and building designs were very much in accordance with the suggestions advocated in the national guidelines. It is clear from the layout that boys and girls were separated. The entrance, cloakrooms and classroom were allocated by gender and the playground divided by a 6ft wall. There were plans for an infants’ classroom to be added some years later. We do not know if the plan was ever carried out. What is clear from the layout is that the infants’ classroom, if built, would have had a gallery. The thinking at the time was that the master would be able to see all his pupils and monitors so that he could make sure that all were behaving. Discipline was severe. The teachers desire to obtain a good result arose because their salaries depended upon the amount of grant the school obtained. The grant was awarded each year following recommendation from inspectors who set and supervised examinations in each school. Inspectors had great powers in deciding the success or failure of a school and its teachers. As an example of the inspectors’ powers, one school in Hampshire which had a grant of £32, 4 shillings in 1872, was reduced to a grant of £9, 4 shillings in 1875. It was not until 1879 that the grant for this school returned to what it had been seven years before. Not surprisingly, the schoolmaster would spend time preparing boys for examinations. The inspection at Bishopstoke National School on 17th July 1866 recorded the following results. Number of boys present for examination 60, of which 56 passed reading; 54 passed writing; and 36 passed arithmetic, giving a total of 146 passes and payment of £19:9s:4d. In addition, grants were also awarded for pupil attendance, although even during the 1860s it was not compulsory that children should attend regularly. Parents also had to pay 1d per week for their child to attend school. If children did not attend school, the income of the school and subsequently the school master’s salary suffered. In rural communities, parents were anxious that their children should contribute to family income and farmers wanted the use of cheap labour. Children simply stayed away as soon as paid employment offered itself or they were needed to support their working families, and there are many examples of these events recorded in the Bishopstoke school log.

On 6th January 1863. William Allen returns after being absent since last May, minding the younger ones.

On 20th April 1863. William Cowding leaves, for a time, as last year, cow minding.

The local gentry also used schoolboys as cheap casual labour. On 20th December 1864, 18 boys were granted leave to go with Mr. Chamberlayne bush beating for rabbits. In March 1867, Mr Barton of Longmead House required a few boys for stone picking.

Harvest time was a particularly busy season and records show that many boys were regularly and repeatedly absent during this period.

Despite these absences, in the inspectors visit of 1866, attendance was adjudged to be average, and the school awarded an additional £11: 8s. per year. The income of the school in the 1860s, allowing for the 1d per week from each child and grants awarded by the inspector, would have been around £50 per year to support teachers’ and teaching assistants’ salaries, books, and materials. Presumably because of good inspector reports, the schoolmaster must have had more support from the clergy and local gentry to expand the Bishopstoke school curriculum beyond the four Rs than many other schools were given in the 1860s.

In 1864, records show the schoolmaster practised 12 boys in reading from a newspaper on the great fire in Santiago (Chile). The following day, he gave them a lesson on the war in Denmark and some of the boys read an article in the newspaper about the first battle. Additional class subjects, such as these, like geography and history were not generally adopted in English schools until 1895. The schoolmaster was also keen to teach them practical skills. An extract from the school records in July 1865 advises that the class practised in measuring with a foot rule and finding the area of different articles. In a more practical application, it later records that the class calculated how much gravel would be needed to cover the school playground. The gravel was obtained, and the boys were despatched to spread the material evenly over the playground and roll it level. The schoolmaster arranged for flower seeds to be planted in the school garden and, when the swallows returned in the spring to nest in the school porch, he gave a strong warning to the boys not to disturb them. The pupils were encouraged to collect wildflowers and prizes were offered for the best collection. It is recorded that one boy, in the 1860s, collected 110 different flowers and, most impressively, knew the names of 80 of them. This makes you realise just how abundant wildflowers were in the village at this time. One hopes for the boy’s sake that they had not been collected from the school gardens, otherwise he would have received a completely different reward to the one he had been expecting.

This is the house designed for the schoolmaster, which stood alongside the National School in Bishopstoke. The first schoolmaster, in 1843, was James Shotter, who lived in the School House with his sister, Ann. Remarkably, James Shotter in 1843, was only 18 years of age. He was also, according to Arthur Drewitt in Eastleigh’s Yesterdays, crippled and had to walk with the aid of a crutch. Those who taught working class children were themselves drawn from the ranks of the working class. The concern that the poor should not be educated above their station led to a belief that teachers, too, should remain appropriately humble. This view dominated teacher training for much of the 19th century.

Prior to the 1840s, elementary teaching was often taken up by those too old, too sick or too inefficient to earn their living in any other way. Adult teachers were normally supplemented by child monitors. These monitors were selected from the older pupils at the age of 12 or 13 and they taught their fellow pupils under supervision. Teaching was little more than repetitive chanting and rote-learning. In 1846, the pupil teacher or monitor system formally adopted was, in effect, an apprenticeship for which they got paid. At the end of their five-year apprenticeship, pupil teachers presented themselves for scholarship examination which enabled the most able of them to attend teacher training college.

Although surprisingly young when he became schoolmaster, by the 1860s James Shotter must have had formal training as he is recorded as being a certificated teacher. He has also married. It is unlikely that his wife would have been involved in school activity on a regular basis as female teachers were, by convention, required to be single. This is why, even today, female teachers are usually referred to as “Miss”. Being a church school, the schoolmaster would have been strongly influenced and managed by the local clergy and would have had to perform duties on behalf of the church. Playing the harmonium at church service and training his pupils to sing hymns was part of a schoolmaster’s contract and ensured that his pupils were “supervised” to be on their best behaviour if they were selected to sing in the church choir. It is recorded that on 15th May 1865: boys were “cautioned at the school by the schoolmaster for inattention in church the previous day. It was not only on Sundays that pupils were expected to attend church service and sometimes the school would be closed during the week. On 10th February 1864 James Shotter notes, Ash Wednesday, lessons until 10.30am, then church, then half day holiday. On 5th May 1864, today being Ascension Day went to church from 10.15 to 12.15. Several boys who went home after church did not return. (Perhaps they thought there was another half day holiday).

Whilst Bishopstoke National School catered for girls, a girl’s education was not considered as important as a boy’s. If a girl was lucky enough to have an education at all it would have consisted of religious instruction, reading, writing and grammar, and the occasional homecraft such as spinning or needlework. Girls from wealthy families were instructed by ill-trained private governesses or in private schools for girls, which were mostly boarding schools. The census from 1861 identifies that a boarding school for girls existed at St. Agnes, in Bishopstoke. The house, amongst the trees on the left of this picture, is where the Toby Carvery now stands. The building in the centre in the far distance is now the Chinese takeaway in Riverside. The school at St Agnes was clearly to cater for girls from select members of society and would not have had any interaction with the National School, half a mile away towards Fair Oak.

The girls’ boarding school was run by Alice Giles and her business partner Louise Poite (who was a British subject, born in France). There was also a German teacher, a nursery governess, a cook and two housemaids. There were only eight pupil boarders, ranging from 7 to 17 years of age to support seven members of staff, although it is possible that there were also day pupils who would not have been listed on the census. Although some of the pupils were from the Hampshire area, there were also pupils from far away exotic places like Bombay in India, Durham, and Lincolnshire. Alice and Louise, who ran the school, had in 1851 been governesses together to the large family of Mr Spencer Smith Esq., Magistrate, of Portland Terrace, Marylebone, London. How, from relatively humble positions they acquired, in a short period, what must have been a large sum of money to lease the property and establish the school is not known. When you consider the ratio of staff to pupils and what must have been high overheads, it is difficult to understand how they made a living.

This picture of Fair Oak Road, is opposite St Agnes, looking towards Fair Oak. The picture would have been taken from the corner of Scotter Road and the entrance to the Toby Inn is, today, just past the gas lamp shown to the right of the horse and cart. Problems arose for the school in 1866 when fever broke out and the consequence was that some pupils went home, never to return. Alice Giles bank account was considerably overdrawn, and she was also in debt for a further £500. She approached, Mr Morris, the Manager of the London and County bank in Winchester. The manager agreed, for her to avoid bankruptcy, to become a trade assignee. He proposed to advance a sum of £200 of his own money to her in return for:

The provision of an inventory of furniture, goods, and chattels (estimated worth £500 to £600) which would be assigned to himself.

Three guarantees for the sum of £50 each from other gentlemen.

The deposit of the lease of St Agnes as security

Provide free schooling for his two children worth £30 each per year.

Provide a promissory note for the full debt.

Whilst this delayed the inevitable, perhaps not surprisingly, in March 1867 Alice Giles was declared bankrupt, although this was not the end of the matter. In March 1868, an action was brought to recover the value of certain goods, which, it was alleged, had been wrongly taken. The case was most complicated and was made so, as there was no clear record of what monies had been paid by Alice Giles to Morris to clear her debt and what chattels had or had not been included in the original inventory list. What is of interest is that Alice Giles, by 1868, had moved to a school in Bishops Waltham run by a Miss Smith, taking what remained of her pupils. She had also taken with her some beds and other articles, claiming that they were not part of the assigned items. By 1871, Alice Giles had moved to Fareham and established a boarding school for girls in the High Street. There was one other teacher (a French teacher), a cook, two housemaids and fifteen students aged from 8 to 17 years of age. Potentially, a far better business with less staff and far more students. The client background was similar to that at Bishopstoke with pupils born in India, France, Jamaica, Ireland, and Canada amongst her boarders. This reflects the level of Military and Diplomatic families who lived in the area at the time. Alice died a spinster in May 1871 and had recovered from her perilous financial position of only four years earlier when she owed close to £1000. She left a respectable sum of £300 to her spinster sister, her only next of kin.

Some of the wealthy residents of the village were benevolent towards the schoolchildren of the parish. Dean Garnier took his role of benefactor further than most. Dean Garnier was a very wealthy man. He had been born at Rooksbury Park, Wickham. His income in the early 1800s as Rector would have exceeded £400 per year, whilst Edwin Simms, at Bishopstoke National School, in 1862, is recorded as having an income of £20 per year as a certificated teacher. Perhaps, it is understandable why in the 1700s and early 1800s so many titled and wealthy families encouraged their younger sons to enter service in the Anglican Church. The Dean enjoyed entertaining children and, with many servants at his Rectory in Bishopstoke and at his residence in Cathedral Close, Winchester, he had many helpers to call on to assist him in handling these occasions.

A typical instance of Dean Garnier’s generosity is when he decided to host a party for 1,000 children from the Parochial Schools in Winchester, at his Rectory in Bishopstoke, on the 14th of June 1848. The article published about the event in the Hampshire Telegraph on Saturday June 17th, 1848 advised that: “For their conveyance a special train was provided; and about two o’clock nearly 1000 children had assembled at the (Winchester) Railway Station and were speedily conveyed to their place of destination. At the Bishopstoke Station, they were met by a band of music, and the children belonging to the Bishopstoke School, some of them bearing green banners, on which were inscribed in letters of gold, the word “welcome.” They then formed into procession, each school being preceded by its appropriate banners, marched through the village to gardens attached to the Rectory House, where they were received with a beaming countenance and a throbbing heart by the Very Revd., and ever beloved proprietor. Seats were placed around the grounds for the children, who were plentifully regaled with cake and tea; and after enjoying themselves for several hours, returned in procession to the Railway Station, and arrived at Winchester about eight in the evening.”

The earliest example of an educational building in Bishopstoke, still standing, is the Bishopstoke Reading Room, which was built in 1875 in what we now call Church Road, at a cost of £800. This building was furnished with a library along with a good supply of newspapers by Capt. Thomas Hargreaves who lived at The Mount and the building had been erected, in part, due to the success James Shotter had achieved at the National School in raising literacy levels. Philanthropists like Capt. Hargreaves recognised that the poor, without access to reading material, would lose the skills they had learnt at school and so he provided access to reading material, for those too poor to be able to buy books or newspapers for themselves. These premises were much more than a simple library. They were used for training in practical skills, bible classes and talks on topics of interest and, in so doing they provided a facility which was used by villagers to continue their learning beyond school age. The Hampshire Advertiser ran an article in September 1875 relating to “The Opening of the Bishopstoke Reading Room and Library.” “Wednesday 8th September was quite a Gala Day at Bishopstoke in consequence of the announcement that the new Reading Room and Library, which for some time past has been in course of erection…. Would be formally opened. The town was gaily decorated with flags… and at 2 o’clock the Bishopstoke Brass Band… played some excellent music close to the Reading Room”. The building, which is situated near the church, has a very neat appearance, and will doubtless prove a great boon to the working classes of Bishopstoke. It is of Gothic design and contains a fine reading room 35ft by 19ft, the walls of which are covered with maps and other useful objects of reference. It also has a unique library, furnished with the complete works of some of our most popular authors, besides a large and miscellaneous selection of books on history, travel and other instructive subjects, there being altogether about 1,000 volumes. This has been furnished, at the expense of the founder of the institute (Capt. Hargreaves) by Mr. Gilbert, bookseller of the High street, Southampton. Attached to the building is a neat residence for its keeper and, in addition to the various periodicals and newspapers supplied, ample recreation is provided by way of bagatelle, chess, draughts etc. for those disposed to indulge in these games. Mr. Serle of Bishopstoke is the builder and Mr. Laishley, of the same place, the decorator, and great credit is due to both for the way in which they have executed their work. At half past 2 o’clock the Institute was formally opened by Captain Hargreaves… amid hearty congratulations and earnest hopes that the boon so appropriately provided would be fully appreciated… After the opening ceremony about 70 invited guests sat down to a substantial dinner, provided in the grounds of The Mount…, which, with the gardens, were thrown open to the public. Here, during the afternoon, athletic and other amusements were indulged in, everybody entering with heartiness into the fun… At 5.00pm tea was provided in a large tent in the grounds… and partaken by some 500 persons. Dancing and other sports were continued after tea until dark, when the grounds were lighted up with Chinese lanterns and different lights suspended from trees, the effect being very picturesque.”

In 1870, the Elementary Education Act established school boards to manage schools where no voluntary or self-funded body was provided. This change in legislation had a major effect on the National School in Middle Street and eventually led to the creation of the new Bishopstoke Board School in Church Road (pictured).

A Mr Jones, had replaced James Shotter in 1875 and during his short tenure, appears to have endured a particularly torrid time from unruly monitors and pupil teachers as well as disruptive pupils, high levels of absence and damning criticism from Government Inspectors. In 1876, it was recorded that due to a national increase in school fees to 2d per week, many children were now absent from school. Mr. Jones appears to have been an ineffectual leader who failed to address disciplinary issues, and was dismissed immediately following a visit by the government Inspector in 1878. The inspector threatened to withdraw funding for the school entirely if improvements to buildings and teaching standards were not put into immediate effect. There were also two pupil teachers, or monitors, who appear to have been ill-disciplined bullies and poor examples to their pupils. There was also a sewing mistress who had no teacher training or qualification. In May 1878, there were 104 pupils at Bishopstoke National School. George Holdaway, one of those criticised by the government inspector in 1878, did remain at the school and later qualified as a teacher and taught at the new Bishopstoke Board School, which was built in Church Road. Despite numerous entries in the National School logbook, referring to his failings and manner as “unbecoming a teacher”, it was recorded that “George Holdaway’s moral conduct had been good”. Moral conduct was highly regarded by teacher training colleges. A student’s future success as a teacher depended less on academic ability than on moral qualities and, particularly so, for women. For women, earnings as teachers were far better than could be obtained in domestic service, the most common type of employment open to females, although earnings for teachers, male or female, were not high. The fact that women teachers received lower pay than men also increased their attractiveness to school managers who had limited cash at their disposal. Edwin Sims returned to Bishopstoke National School, as school master, in Middle Street in 1878, where he had also been a pupil and trained under the monitorial system.

In the 1870s, ratepayers objected to state funds being used to support schools because school funding had always been provided by the church and wealthy landowners. On 16th January 1878, an article in the Hampshire Advertiser reported that “in Bishopstoke accommodation is required for 150 children, and … if the Bishopstoke National School is completed in accordance with the plans which have been approved,” ( possibly the addition of the infants’ classroom following the inspectors criticism’s)… “and conducted as a public elementary school, no further accommodation will be required, and thus the necessity, for the ratepayers, of having to fund a school board avoided.” Voluntary funding was clearly not forthcoming when in June 1878, the Hampshire Telegraph reported the election of a school board in Bishopstoke consisting of three churchmen and two non-conformists. Although now funded by the state through rates, clearly the church was still very much influential in matters of education. To add perspective, this article also advised that there were 332 voters in Bishopstoke who elected the school board and one-third of the eligible electorate refrained from voting; It also reported that 60 (25%) of the influential and probably older householders in the Parish of Bishopstoke could neither read nor write.

Recognising the threat from HM Inspector the newly elected, but still church dominated, school board established plans for a new school to accommodate 160 pupils. This school would be funded from the rates and attendance fees. The inspector continued to support funding for the old school, despite repeated threats not to do so, until the new school was completed. The building of the new school coincided with the Education Act of 1880, which tried to make school attendance compulsory, but failed. The new school opened on 8th December 1880 at a cost of £1,973 for 160 pupils. The following is an account of the opening, taken from the Hampshire Chronicle of 11th December 1880. “On Wednesday last the new board school in this parish were opened. Great interest was evinced in the village… The proceedings began at 2.00pm, with a procession, the children assembling opposite Mr. Barney’s Mill and marched up to the school with gay and appropriate banners. Some minutes were spent marching round the playgrounds cheering. After this they went into the school to attend a religious service…The rector, Revd. R.E.Harrison offered up a short prayer for the blessing of Almighty God on the new building, at the conclusion of which the children sang the hymn beginning “Shall we gather at the river”. The Revd. G. Hills, vicar of Curdridge, then delivered a very suitable address (to the children), impressing on them the wickedness of disobedience to parents and teachers, and urging them to attend well to their studies… The whole of the children were then regaled with plenty of plum-cake; bread and butter, and tea…”

The staff consisted of Edwin Sims, school master; George Holdaway, certificated teacher; Arthur Powell, pupil teacher and Emily Child, an infant and sewing mistress. There were 112 pupils registered. Unfortunately, at the new school, things did not start particularly well. In January 1881, heavy falls of snow prevented some staff and students getting to school and the wall along the south side of the school yard fell down. The west wall of the school yard fell down in March. Further disaster struck a while later. During a particularly heavy storm, a bolt of lightning hit the bell tower and around 100 roof tiles were thrown to the ground. Fortunately, the school had been dismissed early due to the bad weather and, although several pupils were sheltering in the school porch at the time, nobody was hurt. The inspector’s visit in May 1881 was not encouraging and, rather perversely, he criticised the move to the new premises as “prejudicial to the progress of the school.”

The inspector was also critical of work done by Emily Child, the infant mistress. Emily continued to be unpopular with the school inspector in his reports for the next two years and, in some parts of the village, rumours were starting to spread regarding her personal affairs and popularity in other quarters. On becoming acquainted with the rumour, the Board summoned Miss Child to question her conduct. Miss Child emphatically denied any wrongdoing and protested her innocence. Because of her seemingly excellent background and character, Miss Child was permitted to continue as infant class teacher. In January 1884, Miss Child was replaced by Annie May. Emily Child had been “summarily dismissed for immorality of a gross kind.” It transpired that during the Xmas holiday that she had been diagnosed as “with child” and, as a single woman without support, was obliged to become an inmate of the “Winchester Union”, which was the poor house for the area. Annie May had problems of a different kind to contend with. Records of a school board meeting published on Saturday 9th of August 1884 record that Edwin Sims applied for a salary increase. Despite reservations, the request was finally approved, and he was awarded the not insignificant increase of £10 per annum. To fund the increase, the school board agreed to dismiss the infants’ mistress and replace her with a provisionally qualified teacher, on a lower salary. We do not know for certain that this was carried out, but it is probable. (I hope that at least she was informed by the school board before this decision was made public in the local newspaper).

The school population continued to grow and, by 1886, had grown to 152 pupils. Unfortunately, attendance was still problematic. Sickness and occasionally epidemics caused widespread absence in school. In November 1886, the Medical Officer of Health ordered Edwin Sims to stop all children from Fair Oak, Crowdhill, Horton Heath and Middle Street attending school because of an outbreak of measles. 99 children out of 152 (65%) were absent because of this. There were other reasons for absence. In 1876, a new Education Act had made attendance compulsory for children up to the age of 10. This was difficult to enforce as voluntary funded (Church) schools were outside the provision of the Act and not all parents welcomed these initiatives. With hostile attitudes towards education among rural communities, there was often a reluctance among magistrates to prosecute parents for infringements of the attendance by-laws. The population of Bishopstoke continued to grow to house workers for the new London & South Western Railway Carriage Works which were completed in 1890. There was also a change in legislation in 1891, which made elementary education free. More children in the village needed schooling and Bishopstoke Elementary Girls and Infants School was built in 1895, at a cost of £4,000, for 150 girls and 150 infants. The original school building became Bishopstoke Elementary Boys School, with Edwin Sims retaining the role of master. Bishopstoke Evening Continuation School (for adults) was established in 1898 and utilised the school buildings and the Reading Rooms in Church Road. We have records from 1902, recording that evening classes were held from 7.00 to 9.00pm in commercial and practical mathematics on Mondays and Wednesdays, woodworking classes held on Thursdays and drawing classes held on Fridays, at a charge of 2d per week, per class. It closed through lack of attendance in April 1913. Irregular attendance by day school pupils had always been a problem. In December 1899, at a Board meeting, the chairman, Revd. Ashmall, whilst accepting sickness as a reason for absence, was indignant that children were absent from school when it suited their parents. In cases where examples ought to be made, he considered, they were pooh-poohed by the Winchester County magistrates and he believed that this leniency was mistaken as it made parents indifferent to the need to meet obligations for the education of their children. Revd. Asmall publicly declared his intention to attend the court and lay the case before the justices, as he considered it was absurd for them to administer the law as they were now doing. We must also put into context that, before coming to Bishopstoke, Revd. Ashmall had suffered a serious nervous breakdown and was, perhaps, not in the best of mental health.

In1899, The Board of Education Act created a new government department to oversee education and by 1902, school boards were replaced by local education authorities. A board meeting in May 1900 at Bishopstoke school illustrates how deeply opinions sometimes differed between school boards and the education authorities. The recent inspector’s report had criticised the accommodation. The board considered that such a comment amounted to an injustice and demanded to know why such a criticism had been made as the school had only been built some 6 years previously and the plans approved by the education department. Furthermore, the inspector had criticised the heating in the infants’ class. This incensed the school board and Revd. Ashmall in particular, as the fireplace had been made larger the previous year. As far as he was concerned both staff and pupils found the conditions satisfactory. He wrote a letter to the board of education, with the backing of the school board, of which the following is a small extract that illustrates his strength of feeling: “My Board ventures to ask the Board of Education if it is quite fair to them to ignore their efforts to meet the many minute requirements of the Education Department and whether such a matter as the warming of the schools is to be settled by the casual visit of some chilly mortal in the month of February, who perhaps at the time is recovering from influenza. My Board is of the opinion that the officious tongue of a particular person and the too open and receptive ears of Her Majesty’s Inspector are responsible for the demands made in the annual report.” Even in the backwater of Bishopstoke, it was clear that school performance, inspections, and management polarised opinion within the community. Canon Ashmall seems to have been a copious letter writer of angst. In 1900, as Chairman of the school managers, he was concerned with safety in the road outside the school. He wrote to the council regarding his concern: – “At the present time the metalled road (outside the school) is 20 feet wide. The traffic is considerable and largely increasing! There is a constant stream of children along this road, four times a day, for a quarter, to half an hour at a time, and two dangers are imminent: –

- Children rush out of the two school entrances without regard to passing vehicles in a narrow road where space is limited.

- Vehicles come down the very steep hill and cannot pull up to avoid accidents to the children, without risk of injury to the horses. (I leave to your own opinion whether he was more concerned about injury to the horses or injury to the children?)

Revd. Ashmall left the Parish in 1905. Thomas Cotton, who lived at the Mount replaced Revd. Ashmall as Chairman of the school managers. Thomas Cotton was also a Member of Hampshire County Education Committee and Governor of Hartley Institution, which has now developed into the University of Southampton. It is clear from records that Canon Ashmall and Thomas Cotton were diametrically opposed in matters of politics.

This delightful picture depicting the Mad Hatter’s Tea Party was contained in an album of photographs from the old Victorian Bishopstoke schools and is presumed to be from 1913.

Nowadays we take school welfare facilities like meals and healthcare for granted. Welfare facilities were only introduced in schools nationally because, in 1899, three out of every five men enlisting to fight the Boer War were rejected by the military as physically unfit for service. In true Victorian tradition, it was considered a national disgrace that the youth of the country were not fit enough to be killed in the defence of our Nation and action had to be taken. Legislation in 1906 allowed local authorities to provide school meals although it was not until 1914 that local authorities were compelled to feed all needy children within their district. School meals however were not free to those that could afford to pay.

The provision of school medical inspections followed in 1907, although there was no obligation made to provide treatment. Medical treatment was not free, and many families would not have been able to afford to pay for treatment, even if it were needed. Edwin Sims remained master of the Bishopstoke Boys School throughout this period and he finally retired in June 1910 after 32 years’ service. He had spent nearly 47 years at Bishopstoke schools as pupil and teacher.

The new Boys School Headmaster was Frederick Garton. He introduced organised physical activity (games). In this picture Frederick Garton is seen in the centre of a ring of boys who are holding hands. Each boy jumps as the Headmaster sweeps his arm around the circle. The incentive for the boys to jump is a lump of metal attached to the rope which would crack against the ankle of any boy not sufficiently agile. There seems to also be another agenda in this picture. Larger boys seem to be grouped together and pulling away from the reach of the rope, thereby dragging their smaller classmates towards the centre of the circle where they would be more vulnerable.

In the summer Frederick Garton also organised swimming for some of the older boys. There were no such things as swimming pools for schools, so the bathing place was part of the River Itchen, where a fence had been erected for safety. HM Inspector in 1911, whilst praising the introduction of these physical activities, is less than complimentary with the facilities of the Boys School. Examples given include desks being unsatisfactory. All desks are recorded as having awkward gaps between seats and desks, none have back rests, and in several cases, the seats are only 12 to 13 inches high, a quite unsuitable height for big and growing lads; Classrooms being overcrowded, and most dual desks being occupied by three boys; Cloakroom, lavatory and closet accommodation being meagre and the urinal being very malodorous. The urinal was still “malodorous” in the 1950s.

In March 1891, 20 years before this picture was taken, the Bishopstoke school board agreed that prizes would be given to children who achieved 400 attendances out of a possible 441 in the year (90%). Only one child had made every attendance and the board decided to give a special prize for this. £2.10s, in total, was set aside for all attendance prizes. The next meeting of the school board had to reconsider the granting of money as prizes for attendance. The official auditor from the education authority had questioned why funding was being set aside for prizes based on regularity, punctuality, and good work when such actions were compulsory by law. Funding for prizes was withdrawn, although good attendance would continue to be recognised.

Regular attendance is an important discipline to take into adult life and, certificates, such as these from Bishopstoke Boy’s Council School, were used to encourage good attendance. These documents, particularly for the older pupils became reference documents to show to a prospective employer. These certificates were awarded to Frederick Humby. (pictured) They are signed by Headmasters Edwin Sims in 1909 and Frederick Garton in 1911 and 1912. Thomas Cotton has signed the certificates as Chairman of the Bishopstoke School Managers.

Frederick Garton did not remain at Bishopstoke Boys School for many years. He had problems with school maintenance, building contractors, and with managing a growing number of pupils without additional resources. In the summer of 1912, workmen were employed to re-decorate the school. When the school re-opened on 2nd September, paint was still wet and the smell of paint very strong. Far worse was to be discovered. During the summer, school desks had been ruined. They had been left out in the rain for days by the workmen. The ironwork was rusty, and the polish entirely gone. There were more pupils than the school had been designed to accommodate and a temporary building was constructed to ease overcrowding. Mr Garton complained that this was unacceptable as the school had 209 pupils, with staffing for only 190. This resulted in him having to take a class of 41 pupils himself which he considered intolerable and handed in his notice.

The new headmaster of the Boys School was Charles Harold Croft (pictured, centre). The school faced serious staff shortages and, at the beginning of the 1st World War in 1914, fuel and teaching materials are in short supply. Younger pupils are recorded as using plasticine instead of usual craft materials as plasticine can be re-used and was cheaper. Supply teachers did not stay for any length of time and, because of staff shortages, for a period, terminal exams for those pupils leaving school were suspended. The mistress of the Bishopstoke Infants School, Miss Ethel Preece, became Mrs. Ethel Croft in April 1914. They were married in St Mary’s Church opposite the school. Pupils from the school picked primroses and scattered them along the path from the church to the gate when the couple left the church.

These pupils would not have been aware that the simple act of two colleagues getting married would be politically and socially unacceptable. Lady teachers were supposed to be unmarried. The Hampshire Education Sub-Committee, meeting in July 1914, had ruled that, following the marriage between Mr Croft and Miss Preece, Mrs. Croft, as a married woman could not be permitted to retain her position as mistress of Bishopstoke Infants School, and she was given notice to quit by the end of the year. This decision was reviewed at the main Hampshire Education Committee when they met in Winchester during October 1914. The committee decided that married mistresses would, because of projected teacher shortages, be allowed to remain in office for the duration of the war.

The picture probably represents a play or musical that was performed at Bishopstoke Girl’s School. In 1913, the children of Bishopstoke would not have been prepared for the political upheaval that was about to embrace Europe in 1914.

The 1st World War was fought overseas and did not have the same dramatic effect on life at home that later conflicts were to bring, although food shortages and family duties for some of the older children would have disrupted their schooling. Today, we perhaps forget the tragedy of what was termed the “Great War”. In Britain, of the six million men who had been conscripted to fight, 750,000 had been killed and 1.75 million had been wounded. For younger children, like William Humby, whose father was fighting overseas in the Balkans, life centred around their mother. This photo is of the Infants group at Bishopstoke School in 1916. William Humby is seated to the right of the blackboard.

By 1916, the Education Authority was responsible for medical inspections and treatment. If you were diagnosed as suffering from head lice the practice of the day was to have your head shaved by the school nit nurse and an ointment applied to the scalp. The hair would then be allowed to re-grow. As this process took some time the child could wear a cap or scarf to maintain a little dignity. Perhaps this is why the girl on the left in the back row is dressed differently from the rest of the group.

During the war period, the supply of food became scarce. Men were no longer available for heavy farm work, so the school field was dug up for the children to grow vegetables. Gardening classes were introduced and held once per week.

Certificates were issued to children who provided Xmas food parcels for the troops serving abroad. The bottom picture is a school certificate celebrating Empire Day in 1916 which was awarded to children who had sent some comfort to troops serving in the Great War. The first ‘Empire Day’ took place on 24th May 1902, in recognition of the late Queen Victoria’s birthday. Although it was not officially recognised as an annual event until 1916. Each Empire Day, school children across the British Empire would typically salute the union flag and sing patriotic songs like Jerusalem and God Save the Queen. They would hear inspirational speeches and listen to tales of ‘daring do’ from across the Empire, stories that included such heroes as Clive of India, Wolfe of Québec and ‘Chinese Gordon’ of Khartoum. (Presumably, none of these gentlemen warrant a mention in the curriculum of today). The real highlight of the day for the children was that they were let off school early so they could take part in marches, maypole dances, concerts and parties that celebrated the event. By the end of the 1st World War, recommendation was made to raise the school leaving age from 12 to 14 and this was implemented under the 1921 Education Act. Gardening classes established out of necessity during the war years became a regular part of the school curriculum.

The successful growing of food is, as ever, weather dependent. It is recorded in the early 1920s that some gardening classes had to be cancelled and, frustratingly, at harvest time, potatoes could not be got out of the ground. In 1924, the lower portion of the school garden was waterlogged and half the plot that had been planted with potatoes, failed to grow. Even so, in 1925 the school made a profit of £3:19s on its produce. Later, in 1926, the school gardens were pronounced “one of the best kept school gardens in Hampshire”, by a school inspector. School inspections immediately after the war reported a not very good standard in the three Rs. Not surprisingly this had been a period when many of the older boys had been kept from schooling by family pressures and some of the male teachers from the school had been conscripted into the armed forces. Religious instruction fared better, probably due to the intervention of Revd. Sedgwick, and a comment is made that “the children understand what they have learnt and give spontaneous and intelligent answers”. School inspections continued to criticise the condition and maintenance of the premises. Frederick Garton had raised issues with the caretaker before he left, various school inspections criticised cleanliness, and in the early1920s conditions were not improving.

In January 1920, an entry in the school log, by Charles Croft, records that at 9.00 o’clock am the average classroom temperature was 34 deg.F, one classroom recording a temperature of 30 deg.F. Water freezes at 32 deg.F and icicles had formed in some classrooms. The children were numb with cold and written work had to be abandoned as boys could not hold their pens. Several entries are made in the school log regarding the filthy state of the school. In October 1921, “dirt in school. Bowls in lavatory not cleaned for 5 days. Got boys to clean washbasins. April 1922, conditions of floors much worse. Heaps of dirt left under desks. Pupil teachers and boys brushed floor before school. Urinals and water closets in same state.” There is no explanation as to how these conditions arose.

This picture was taken at Bishopstoke Boy’s School in 1922. The school attendance officer and caretaker from 1897 to 1922 was George Sangster who lived at No 4 St. Margaret’s Road. Members of his family still live in the village. He had been a sailor in the Royal Navy before joining the school and, during his life, had faced much adversity.

Whilst George Sangster served in the Navy, his wife and family lived in Plymouth. In one year, his wife and seven of his children died. He served aboard H.M.S. Carysfort, in 1881. Two of the ships company were the sons of King Edward VII, one of whom became King George V. He also served as guard of honour to Queen Alexandra when she made a voyage from Norway to England. He had been shipwrecked on two occasions. One ship, with 700 people aboard, was burnt out at sea and George Sangster was one of only eleven saved. On another occasion, when hundreds of lives perished, he was one of only seven saved.

He retired from the school in 1922 at the age of 78. It may have been personality issues between teachers and caretaker that led to criticism of school standards or, at the age of 78 he may not have been able to carry out his duties as well as he was once able. He was well regarded in the village. Whatever the reason, we can only perceive the difficulty any Headteacher would have faced if they ever wished to dismiss such a grand old veteran.

Charles Croft left Bishopstoke Boys School in October 1923 to become a school inspector. Patrick James McGregor became the new master of Bishopstoke Boy’s School. In 1925, the head of Bishopstoke Girls School, Miss Moore, became head of the Bishopstoke Junior Mixed School with pupils aged from 5 to 11 years old. Miss Moore served the school as Headteacher for more than 20 years. The original school buildings, built in 1880, became Bishopstoke Senior School, for pupils aged between 11 and 14.

This is a picture of Miss Street’s class taken in the 1920s or 1930s. Miss Street was born in Bishopstoke, in a cottage which used to be at the back of “Weymouth House”, at the top of Church Road. It shows a small class with only 28 pupils and, although sparse by modern standards, pictures adorn the walls and teaching aids for reading are displayed. This is in sharp contrast to the classroom conditions that prevailed less than 100 years previously when school rooms were described as having “no furniture but a teacher’s desk, a few rickety forms, a rod, a cane, and a fool’s cap.” One consistent feature in classroom teaching was the blackboard. Free standing boards were used in classroom teaching from Victorian times well into the 1950s and consequently the term “Talk and Chalk” became a standard description of teaching methods.

This tatty, treasured, and delightful picture, presumably from the same period as the previous picture was taken in the Bishopstoke Junior Mixed School. The room, whilst too large for one class, was divided by portable screens to separate different classes. The provision of reading material, since Victorian times, had been a concern in schools because of cost. Writing materials were less of a problem, because slates and chalk were widely employed, thus reducing to a minimum the amount of paper that had to be purchased. Writing in ink, in a copy book, was reserved for older children in the Senior School and, to “blot one’s copy book”, was considered a major crime.

The 1920s and 1930s brought mixed blessing to the Bishopstoke schools. Improved welfare with regular medical inspections and the provision of school meals resulted in positive comments in the school medical officer’s report. There were congratulations on the pupils’ general cleanliness and the County Council Dental Surgeon genuinely praised in his report of 1926 that less than half (43%) of pupils possessed perfect teeth.

High turnover of staff in the senior school during the 1930s had a detrimental effect on teaching. Inspectors’ reports criticised poor class control and excessive punishments being administered. One incident report at Bishopstoke concerns an irate mother complaining to the master about a teacher “inflicting wounds and weal’s on her daughter’s arms.” The head defends the teacher and suggests that the mother beware of making false accusations. The matter was not dropped as the head had hoped and he was summoned to a meeting of the Education Authority in Winchester to account for his comments. We do not know what action, if any, was taken against the head teacher. We do know that, because of the inquiry, the teacher involved is later given a formal warning as to unsatisfactory work and later leaves the school.

Despite the angelic appearance of these children at Bishopstoke School, the most common means of maintaining discipline in schools was corporal punishment. While a child was in school, a teacher was expected to act as a substitute parent, with many forms of parental discipline open to them. This often meant that students were commonly chastised with the birch, cane, paddle, or strap if they did something wrong.

At Bishopstoke schools in the 1920s and 1930s it is recorded that the school inspector criticised excessive punishment applied to unruly pupils. The records of the time recorded who, for what, when and what method of correction was applied. One or two of you may be dismayed to learn that there are copies of these records. Caning in British state schools in the 20th century was usually administered by the head teacher. In many schools in England, it was used mostly for boys, although in Bishopstoke School, records show that girls were caned as well as boys. Girls were only caned on the hand, whilst boys took the full force of the master’s wrath on their seat. Some names appear more frequently than others and some boys received the cane on both hands and seat. Girls were subject to one stripe of the hand for offences such as: opening desk without instruction; inattention; laziness; talking; and laughing aloud in class. The severity of punishment was regulated according to the crime and for more serious offences, like “writing a love letter to a boy”, the punishment of two stripes on each hand was administered. Wilful disobedience like impudence and insubordination to teaching staff warranted three stripes. Continuously producing poor written work resulted in four stripes for quite several girls and, the girl who failed to learn from her mistakes and laughed at the teacher after being admonished for disobedience received six stripes. Punishment for boys was similar to that for girls. Continuous talking initially warranted two stripes on each hand but, as one unfortunate boy discovered, the punishment was increased to three stripes when he repeated the offence a few days later. Records show, you will be pleased to hear, that he learnt his lesson and did not receive another punishment for almost a year. Many boys received punishment on both hands and seat. Disobedience seems to have carried a standard punishment of one stripe on each hand and two on the seat, whilst truancy raised the level to two stripes on each hand and two stripes to the seat. The level of punishment did depend on who was the master at the time and three boys, in 1939, who received only three stripes to the seat for “filthy conduct in offices”, were perhaps fortunate to have their punishment dispensed by a more lenient master than some who had previously administered these matters. It is, perhaps, easier today, to think that these punishments were token acts to change a pupil’s behaviour. They were not and were delivered with gusto and righteous belief. Usually, there was a maximum of six strokes (known as “six of the best”). Caning would typically leave the offender with uncomfortable weal’s and bruises lasting for several weeks. A headmaster’s caning of a 13-year-old schoolboy at an English grammar school in 1987, when he received five strokes for poor exam results, left “severe bruising”, and, according to his family doctor, five separate weal’s. The headmaster who gave the punishment was prosecuted and cleared of the offence of assault occasioning actual bodily harm, with the judge in his summation, commenting “If you get a beating you must expect it to be with force.”

The 1936 Education Act raised the school leaving age to 15, but it did allow employment certificates to be issued to permit 14-year-olds to work rather than attend school. These certificates were supposed to be issued in circumstances where a family would suffer hardship if the child did not work. However, it was to a school’s advantage to grant certificates to leave school at the age of 14 as it helped to relieve pressure on overcrowded classrooms. In 1936 lack of accommodation was still a handicap to Bishopstoke Schools. The senior school had no science room, no staff room and only 4 classrooms. There were 225 pupils with more than 50 pupils in some classes. A temporary building had been constructed in the playground where the girls have classes in domestic subjects, but the boys had to walk to Eastleigh for their woodwork classes. To relieve congestion, the senior and junior schools swapped buildings.

School inspector reports continued to be negative. Low standards of work are criticised with remarks such as “dull and lethargic”; “show no enthusiasm for any subject” and “are difficult to rouse.” Teaching is also heavily criticised by the comment, “badly taught”.

If weak academically, at least there was some good news. As this, and subsequent pictures show, pupils were encouraged to partake in plays and the school excelled at sport. The boys’ football team had won two cups and had not lost a match in two years, whilst the girls netball team was top of the local leagues. Some extracurricular activities were arranged to broaden understanding and develop interest. Local speakers were invited to the school. Henry Ivill, proprietor of The Eastleigh Weekly News, gave a talk about the history of printing, and perhaps of more interest to some of the pupils, a visit to Eastleigh Printing Works was arranged. Time off school came at a price and those that went on the trip were expected to write an essay about their visit afterwards, which had to be scrutinised by their teacher.

Another speaker gave a talk on temperance and the evils of drink. I suspect that such talks were, to many of the children, of limited appeal. There were visits to the Locomotive Works in Eastleigh and to the docks in Southampton to see the S.S. Queen Mary. On one occasion, the school was closed for children to go and see a play – Alice in Wonderland. To meet the demands of an increasing population, the decision had been taken that Bishopstoke Council Schools would become Bishopstoke Primary and Junior School, taking pupils only up to the age of eleven. When the school closed for the summer holidays in July 1939, all pupils, who would normally have returned to the senior school for the Autumn term, were reallocated to schools in Eastleigh. The decision to transfer children to schools in Eastleigh must have been questioned when, as they were about to start at their new schools, on 1st September 1939 Germany invaded Poland and World War II began.

Bishopstoke and, to a large extent, Eastleigh, although not unaffected by air raids, escaped the ravages of war relatively lightly compared to cities like Southampton, Portsmouth, London, and many of the large industrial towns in the Midlands. Nationally, the Second World War had serious effects on the country’s children and their education. By the end of 1939, a million children had been evacuated and many had had no schooling for four months. By 1943, almost half a million children had been evacuated from London alone; gas masks had been distributed at the start of hostilities and had to be always carried. Even in rural communities like Bishopstoke, gas mask practice was a regular feature of school life.

A problem that faced the Bishopstoke schools during the war was a constant turnover of teaching staff. There were now married women teachers in the school with husbands serving in the armed forces. If their husbands had leave, then their wives wanted to spend time with them. If their husbands were posted to other parts of the country, they moved to be with them. The inspector’s report of 1945 reflects concern on staff turnover and poor achievement by the pupils. Conditions at the school were also cramped with still well over 50 pupils in some classes.

School meals are provided but there were no dining facilities, so a classroom was reorganised at lunch time for food to be served and then, returned to become a classroom again for the afternoon lessons. This meant that dining tables had to be stored in the classroom which made space very restricted for the children who had to be taught there. With so many men away serving their country, there was a lack of male influence in many families. This may partly explain a serious disciplinary issue that occurred in 1945 when a pupil was removed from class for violent and dangerous behaviour. A report was made to the education committee with the request that he be removed from school. A week later, he was “troublesome” again, and his mother was asked to attend. She was informed that he was not to be allowed to bring knives to school and the knife that had been taken from him previously was returned to her. It is, perhaps, not surprising that this pupil was later permanently excluded from public elementary schools.

War is often a catalyst for change, and we have heard that the Boer War and 1st World War had accelerated national changes in the education and welfare of schoolchildren. The 2nd World War was also to change the view of education in England and Wales.

In 1940, Winston Churchill had a vision that, when hostilities were over, “educational measures would be needed to establish a state of society where advantages and privileges, which hitherto had been enjoyed only by the few, should be far more widely shared by the men and youth of the nation as a whole.” The Board of Education met, not too far away from us, in the Branksome Dene Hotel at Bournemouth in October 1940. Their proposals were set out in a Green Paper titled “Education after the War”. These proposals formed much of what was to become the 1944 Education Act. The Act established a nation-wide system of free, compulsory schooling from age 5 to 15. The school leaving age was raised to fifteen in 1947 and the Act said it should be raised to 16 as soon as practicable, although this was not to happen until 1973. The 1944 Act was, in many respects, progressive and forward-looking and remarkable because it was conceived in the depths of war. It extended the concept of education to include those beyond school age and recognised the value of adult learning and the recreational benefit of education. At Bishopstoke School, the end of World War Two is recorded in the school log for 8th and 9th May 1945 very simply as “School closed for V.E. Day”.

This is a picture of V.E. Day celebrations in Hamilton Road. The years immediately following the war brought hardship and food shortages. On the 23rd of May 1946, a parcel of food and soap was received at Bishopstoke School from the State School of Wynard in Tasmania. This food parcel was shared amongst 5 children who had sadly lost their fathers in the war.

Although the war in Europe was over and men folk were returning home, there was still a battle raging in the Far East. The allies celebrated V.J. Day on 15th August 1945 and the school was closed again for celebrations. This is a picture of V.J. celebrations in Drake Road.

In October 1946, Miss Moore retired as head teacher after more than 20 years’ service and was replaced, on a temporary basis, by Ron Jelfs before Clifford Penn-Marshall became head in January 1947.The school was still using a classroom for lunchtime dining in 1947. The school also had no facilities for cooking and meals were prepared and delivered daily from a depot in Chandler’s Ford. The depot must have had a problem in September 1947 as the provision of meals was suspended. The school had a visit from a representative of the Public Health Department to enquire if any of the children who took school dinners had been ill. Three pupils’ names were given to the official and. it appears that whatever the problem was, it had been resolved as the meal service resumed a few days later. Food was not the only shortage to be found after the war. Housing, or more particularly good quality housing for families, was in short supply. Men had returned from the war and their wives had been pleased to see them. One thing leads to another and nature took its natural course. Many families rejoiced with new babies in the years that followed. By the early 1950s, these children were becoming of school age. The one thing that there was no longer a shortage of, was children, who needed an education.

In the early 1950s, the Longmead Estate, which had once housed a grand country mansion, was developed for social housing providing hundreds of new homes.

Bishopstoke, which had once been a select Victorian enclave for the wealthy and privileged had, after 100 years, lost most of its large houses with their wealthy owners and become part of a national programme of social engineering to accommodate working class families. There is no doubt that such housing was needed, and the construction work provided employment for many men. However, the impact of such a large increase in birth rate and the arrival of so many new families had a massive impact on the ability of Bishopstoke’s old Victorian Schools to cope. When the Bishopstoke boys, girls and infant schools were built they were designed for 460 pupils. By 1956, there was not enough room for all the registered infant and junior school children to be accommodated, despite temporary classrooms having been constructed. Some children now had to be taught in the Labour Hall in Sedgwick Road, and the old Village Hall at Riverside, where the Memorial Hall stands to-day. Other children, with their teacher, had the luxury of being bussed daily to temporary classrooms near Merdon Avenue School in Chandler’s Ford. These classrooms were a short distance from Merdon School and had their own toilets and a small play area. Meals at lunchtime were taken at Merdon Avenue School, although there was no interaction with any of the schools’ children or staff. The school day followed a normal schedule, so teachers and pupils had to board the bus at Bishopstoke School early and arrive back late after the school day had finished. For some that endured this for nearly a year (like me), it was quite tedious, but the bus ride was fun.

Gardening classes, which had first been introduced at Bishopstoke Schools in the 1910s, and had received glowing reports from the school inspector, were still held in the 1940s and 1950s. This group of lads can be seen pictured with their teacher Mr. Jelfs, who some of the residents of the village will remember from his time as a teacher at the “old School”, as well as his time teaching at the new Bishopstoke County Junior School in Underwood Road.

The old schools did not have an area for performing school plays, although school plays were always popular. The highlight of the year for the Infant’s school was always the Nativity Play which was held in St. Mary’s Church. There were two evening performances, and every child took part. Some of the Junior school pupils performed plays in the old Village Hall, as can be seen from this picture, before they moved to the new school in Underwood Road.

Plans for a new Junior School were developed, and the new Bishopstoke County Junior School in Underwood Road was completed in April 1958. To give some idea of the scale of the problem when Bishopstoke County Junior school opened in April 1958, it had 343 pupils and 8 classrooms, a growing population, and an average class size of around 42. Within a year, plans were developed to add a further 4 classrooms (a 50% increase) and this work was completed during Autumn Term 1960. By the early 1960s, in the accommodation that exists now, there were 530 pupils and an average class size of 45. Some classes, as in Victorian days, had well over 50 pupils. Today, with a far larger population in the village, there are around 360 pupils at Stoke Park Junior School.

The official opening took place on 9th May 1958. Mr Oaksford, the chairman of school managers was handed the key and formally opened the front door. The official party proceeded to the school hall where Canon W.V. Lambert the Vicar of Eastleigh and, a school manager, conducted a Service of Dedication followed by the obligatory speeches. Mr. Oaksford was presented with a pipe and tobacco pouch by the head girl and head boy.

On the 14th May the first school sports day took place in the school playing field at 2.00pm in rather cold and windy weather. Speeches of thanks were made, by the headmaster, to thank staff for organising the event, parents and friends of the school who had acted as stewards and canteen staff who provided refreshments. Trophies were presented by Mr. Oaksford and Raleigh House won the aggregate cup. Mr. Oaksford also made a speech explaining to the children the importance of sport and games as part of their education.

The next day Mr. Penn Marshall encouraged a little better performance from the school in punctuality. He gave a special talk at morning assembly about lateness in arriving for first morning lesson, which seemed to be developing amongst some children. In the more cynical world in which we live today, perhaps it would be questioned if his comments were targeted to the wrong audience. If you were late for the first morning lesson, it is probable that you were not in morning assembly either and therefore were not able to hear his words of wisdom.

On the 23rd of May 1958 the first school trip, organised and supervised by Mr. Lloyd, took children from the upper school to Heathrow Airport and Windsor for the day. In those days there were special viewing galleries and balconies at the airport, from where you could watch the planes land and take off.

On the 6th of June 1958 Eastleigh (Bishopstoke) Swimming Pool opened for the summer and swimming lessons were organised for Monday mornings, Tuesday, and Thursday afternoons with transport provided by Coliseum Coaches. The school swimming season was short, although the pool was enjoyed by many pupils during the long hot summers we always seem to remember from our childhood. Many of us learnt to swim through the school. If I remember correctly, the beginner’s certificate was awarded for being able to swim one width and the elementary certificate awarded for being able to swim one length. Once you managed to swim one length you did not bother about doing any more certificates. On July the 2nd 1959 the school held a swimming gala at the pool which was won by Raleigh house.

Tragedy was to follow. On the 6th of July 1959, P.C. Clifford, the village policeman and a detective Sergeant from Fareham attended Bishopstoke County Junior School to interview all pupils who had been at the swimming pool the previous Saturday when, sadly, a twelve-year-old girl had drowned. This interview was done in private, in a closed room, with just the detective and each pupil without any teacher or parent present. Things would be handled differently when interviewing 10-year-old children nowadays.

July was usually a difficult month for schools in the Eastleigh area. Pirelli General and British Rail were the two biggest employers and each company closed for two weeks summer holiday, although not usually on the same two weeks. This meant that if families wished to take holidays together, children had to be taken out of school, which is what usually happened. Average attendance figures dropped from around 95% to 70% over this month.

At the beginning of the Autumn term in 1958 pupil numbers had risen from 343 to 378, virtually the same number that the school has today, although then there were only eight classrooms. On the 14th of November 1958, the school managers received a letter from the Primary Education Sub-Committee agreeing in principle to the immediate extension of the school by the addition of four classrooms to create a three-form entry school. The same week the school library was opened with teacher Mr. Lloyd undertaking the role of chief librarian. There are many visits to the school by the Education Welfare Officer and the school nurse is a regular visitor to check children’s heads for lice. There are also hearing tests and eyesight tests carried out by a specialist technician and, perhaps of far more concern, there is a visit by Dr. Boyle and the school nurse on 21st November to vaccinate selected children against Poliomyelitis. Poliomyelitis is a viral disease that can affect nerves and can lead to partial or full paralysis. At its peak in the 1940s and 1950s, polio would paralyse or kill over half a million people worldwide every year, particularly children. December and January were periods when testing took place for pupils that would be leaving the school in the summer.

In 1950s Britain, the education system, according to Derek Gillard in his book “the History of Education in England”, reinforced the notion that working class children were of lower intelligence. The ‘top’ twenty per cent of children went to grammar schools with the rest going to Secondary Modern Schools. Selection for Grammar Schools was made largely based on the ‘eleven plus examination, which usually consisted of tests of intelligence and attainment in English and Arithmetic. In the eyes of the public, children either ‘passed’ it and went to the grammar school or ‘failed’ it and went to the local secondary modern. This system was based on the notion of IQ (intelligence quotient) promoted by the now-discredited educational psychologist Cyril Burt. The eleven plus – and the continued existence of large classes through the late 1950s – forced the new schools to continue with the class teaching approach inherited from the elementary schools, with its emphasis on basic literacy and numeracy. The system also had a damaging effect on the new Junior schools, like Bishopstoke County Junior School, the success of whose pupils in the eleven plus quickly became the measure by which the school was judged.

On 30th January 1959, Mr. Jelfs took 42 children to Eastleigh County Secondary school, in Desborough Road, for Secondary Entrance examination. Presumably, this examination was to assess pupils for streaming in ability groups. On 21st April 1959, the school was notified that only 6 pupils had been considered suitable for Grammar School education. As 78 pupils were leaving the school this is a very low number and well below the targeted national standard of 20%. The following year, again only 6 pupils were considered suitable, although another 6 were subject to further consideration. On 29th September 1959, the building work started on the much-needed extension to the school which would add another block with 4 additional classrooms to the school, however not all went well and on 7th September the contractors stopped work because the contract had not been signed. This was rectified and work recommenced on 12th September. Things did not fare too well on 8th December either, when again work again had to stop, this time because of wet weather. Work did not recommence until 4th January 1960. When the school re-opened on 6th January 1960 it had been re-named Stoke Park County Junior School.

On the 24th of July 1959 Mr Way & Miss Riddlestone were presented with a collection which had been raised for their forthcoming marriage and departure for a new life in Whitstable, Kent. On the 30th of November 1959, the caretaker reported that someone had entered the school during the weekend and interfered with various drawers etc. The only article missing being a Manilla folder, taken from the assembly hall and belonging to a teacher. The matter was reported to the police, and in response to such a heinous crime, two detectives subsequently called and took statements, after making investigations.

At the start of autumn term, in 1960, the extension to the school is not completed, although the four classrooms are being occupied. Desks have not arrived for two of the classrooms and no wall blackboards have been fitted. There are now, just over two years after the school first opened, 12 qualified teachers, a specialist needlework and backwards group teacher. There are now 459 pupils registered at the school.

On the 20th of June 1960, Rose Organ, the cook, drew the attention of the Headmaster to the meat that had been delivered from the usual supplier and immediately placed in the refrigerator. The Headmaster contacted the public Health Officer who issued a certificate of contamination and issued a notice for the meat to be removed for destruction. Sometimes accidents happened in the kitchen. On 24th November 1960, Vi Curtis badly cut her finger. The school tried to find a local doctor who could provide the necessary treatment. On failing to do so they took police advice and one of the senior school mistresses took her to South Hants General Hospital for treatment. Lessons were not learned and on 23rd June 1961, Rose Organ, also cut her thumb, and had to be taken to hospital for stitches. The school routine settled into a regular round of medical checks, school trips, concerts, plays and exams. There must have been a moments excitement when, on 27th February 1962, one of the boiler room doors broke off as the result of an explosion, although fortunately no one was hurt. It is difficult for us to imagine, but on the 22nd of March 1961, two teachers took the school football and netball teams to Shakespeare Road School for matches, catching the 2.25pm bus. When Autumn term commenced in September 1961, the school now had 489 pupils.

On the 29th of January 1962 the Headmaster, having taken a music lesson in the hall rather than getting the caretaker to help, decided to move the piano himself. Whilst doing this, one of the castors locked and the piano fell over onto its back. One hapless boy failed to move out of the way quickly enough and received injuries to his left foot and leg. First aid was applied, and he was taken home. Later the school caretaker had the job of taking the lad and his mother to hospital in the Headmasters car. By Autumn 1962 school numbers increased, with pupil numbers now 511.