Reminiscences and Rhymes

By George Morris

Dedicated to Agness – my Sweetheart for sixty-eight years.

(George Morris and friends at Breach Farm, Bishopstoke)

Introduction

Bishopstoke History Society were gifted a manuscript by George Morris that had been stored in the Stationers in Spring Lane where it had been held for many years and suffered some water damage. We do not know why it was never published. When we examined the document, we found it to be a wonderful record of what it was like to grow up in a then semi-rural community before modern conveniences both here in Bishopstoke and on the Isle of Wight from where the family originally moved from, and we wish to share these recollections and poetry with you. The poetry is humorous, well written and needs to be read in the style of Pam Ayres, although much of it is likely to pre-date her popularity. This poetry also reflects life from a bygone era. If you only read one of these poems, which I accept may not be of everybody’s taste I recommend “The Trip to Lunnon Town”. I have tried to follow the original script with my two fingered typing and wrestled with auto correct on numerous occasions. The original manuscript has been returned to the Morris family, who have kindly allowed us to copy some of their family pictures which I have used to illustrate the stories. Additional pictures from Bishopstoke History Society have also been used for illustration. The article is rather long at over 48,000 words but highly recommended as a record of country life in the 1920s and beyond.

I hope you enjoy reading it. – Chris Humby MSc

Index.

- Memories of the Isle of Wight

- Cowes Regatta

- The Haymarket

- Breach Farm

- The Water Meadows

- Highbridge to Eastleigh – and back

- The Changing Years

- Clanfield

Poems by George Morris

- Those Quality Mushers

- A Trip to Yesteryear

- Christmas Memories

- Peter’s Passion

- What a Choice for a Birthday Present

- The Trip to Lunnon Town

- The Kitchen Ceiling

- I Wonder What Dickens Would Have Said?

- The Sunday Joint

- A Much-Kneaded Rise

- Beccy

- The Otterbourne Odyssey

- The Reversal

- Taking The Rise

- The Rat Race

- More Changes

- The Flowers of Bishopstoke

- The Passion Killer

- A Visit to Landford Wood

- The Little People

- The Loons

- Our Jim

- The Suet Duff

- Our First Camp

Memories of the Isle of Wight

1914 to 1922, nearly seventy years ago

I was born on the Isle of Wight in 1914 and we, as a family “emigrated” to Highbridge Farm, near Eastleigh, on the mainland. I was eight years old at the time. To a real Isle of Wighter I suppose that makes me an “Overner”, and yet, I feel, somehow, that I belong over there. We’ve visited many times since and had a number of very nice holidays there.

My surname, Morris is, over there, well known. A friend who is also a distant relative, recently supplied me with a copy of our family tree back to the late sixteen hundreds. She said it would have been easier to investigate the Smiths.

Those of our family who were most well-known – that is, in my time – were three brothers, William, George, and Harry.

William and George farmed for many years at Great Pan, just on the outskirts of Newport. George was, for years, head shepherd but, in the time that I knew him, unfortunately, a victim of severe arthritis and so attended to the paperwork. His wife Lavinia, known to us as Aunt Vin was one of another well-known Island family, the Shergold’s. She was a neat, petite little person, always impeccably dressed but who, to a growing lad, wasn’t exactly a favourite. If I went there to tea, she would count the slices of bread and butter that I ate and the slice of cake to follow was miniscule. George and Lavinia had two children, Fred and Freda. In later years Fred went out Freshwater way as a farm manager. Freda married George Weeks who had a confectioner’s shop and restaurant in Newport Square.

William, known to all as “Varmer” attended to the outside business and organised the practical running of the farm. He did more than his share of the manual work himself. He was a well know character around Newport- or should I say, “Nippert?” The milk produced was retailed around the town by pony and float and much was made into butter, fresh and salt. William’s wife, Annie, was the butter maker and people travelled from miles around to get it.

I can remember, before a cream separator was used, the milk was poured into large, shallow skimming pans which stood on slate shelved in the dairy. After settling, the cream was skimmed off with perforated ladles and then turned into butter in end-over-end churns. Most of the skimmed milk was fed to the pigs; this was excellent for fattening, and, I was told, was what made their tails curl.

The farmhouse was large and old. I think it is now a listed building. At the back was a large covered and paved area, in the centre of which was a well with a pump. Beyond was the bakehouse, also paved – or was it brick floored? To one side were the large bread ovens and often I’ve seen whole cart load of faggots stacked ready for the next baking session. I can smell the newly baked bread even now.

Aunt Annie also attended to the poultry. I think the proceeds were her “perks”. She bred and reared turkeys, geese, hens, and ducks. What a hive of industry there was, especially at Christmas time; it was all hands to plucking. How Aunt Annie coped with all this I can’t imagine. She weighed about sixteen stones and rode a tricycle: poor old trike! She had a family of six- Albert, Millie, Ella, Ena, Roy, and Joyce. I think that, in time, Albert went out into the Island to farm and some of the girl’s married farmers. I’m afraid that over the years, we’ve lost touch. I always enjoyed going to Aunt Annies. No matter whether or not you had recently eaten, out would come a round of beef – about a foot across – and the slices would cover a large dinner plate – with mountains of veg. It was more than enough to warm the heart and fill the stomach of any growing lad. Do you wonder that Aunt Annie was my favourite?

I can recall to mind, quite clearly, some of the workers on the farm, most of whom had been employed there all their working lives. There was old Harry Pitman, head carter; Charlie Scivier, under carter, and Stan Holbrook. Mr Way was head dairyman. I never knew his Christian name; for some reason, unknown to me, he was known as the Professor. Of course, as you would expect, he was always addressed as “Fesser”; he had a habit of talking to himself, and when asked the reason, would reply in his low, gravelly voice, “Oi loikes t’ talk to a zensible man”. There were others who worked on the place, but I can’t remember them.

The farm was, I think, about six hundred acres, and carried a large dairy herd, many pigs, and a flock of three hundred or more sheep. Varmer George was, at one time, head shepherd. There were many acres of arable – wheat, oats, barley, mangolds and swedes etc. Much of the acreage has now been transformed into a residential estate. The old house still stands. I should think it would now be a listed building. The yard still remains, but the old cow stable now houses the ponies of a riding club; the horse stable and adjoining buildings are used as an egg distribution centre. The pond where the horses and cattle drank has disappeared completely.

I realise how time changes things but, when I stand in the yard and look around, I seem to see and hear those characters activities of old. I see the teams of tired horses as they come in from a day ploughing up in Pan Woods and watch them as they enjoy a much-needed drink, their harnesses removed, a good brushing and combing, and to appreciate a good meal of oats, chaff and hay. I also hear the rattle of the milk buckets from the cow stable and ‘Fessors Ways voice saying, “Git awver Vi’let; Ya clumsy ol’ vool”.

These strong feelings of nostalgia show my age, don’t they!

My father worked for a while on the farm before we emigrated to the mainland – but more of that later.

William and George’s brother, Harry became my grandfather. I think for a while he farmed in Burnt House Lane and, whilst there, married young Ada Rose. After they married, they took over Baskets farm at Rew Street, Gurnard and it was there that their family was born – Reg, my father, Herb, Bern and Nessie. They went to school in Gurnard and the whole family attended the Primitive Methodist Chapel there. Harry was, for a while, Sunday School Superintendent and, until his death, in 1956, was one of the trustees.

When Reg was twenty-two, he married a young girl from Cowes, Rose Allen, the daughter of a real old sailor, Lewis Allen. I call him a real old sailor because he was born in 1854 and ran away to sea at the age of eleven when sailing was sailing. I later years he sailed on the Duke of Hamilton’s yacht, The Goshawk. Afterwards he served on The Thistle; this was the yacht of the ex-Empress of France, Eugenie. She was the widow of Napolean the Third. He ended his working life as a rigger in one of the Cowes shipyards. He died in 1945 at the age of ninety-one. As I remember him, he was a great character and a great favourite of mine.

While living in Newport we often visited Grandpa and Grandma Allen in Arctic Road, Cowes. They lived almost opposite Mill Hill Road railway station, and I can still hear those little “Puffing Billies” as they emerged from the tunnel under the town pulling the square-wheeled coaches on their way to Newport.

The front room at No 26 was like a museum; it was literally filled with mementoes which grandpa had brought back from his world-wide travels. The three-feet long sword from a swordfish hung on the passage wall; there were shells of all shapes and sizes; lava from Mount Vesuvius and much more. What fascinated me most, I think, was the piece of material on the overmantel, resembling a piece of mahogany. It was in fact a piece salt beef that had been issued to him for his dinner many moons before, he conscientiously varnished it every year. Another fascination was the stair well; this was not of wood but rope, at each end of which was a Turk’s Head. This, too, had an annual varnishing.

I can well understand young Reg falling for Rose; she was a smasher! She later became my Mother. When first married they lived in Palance Road Chapel. Soon we moved to the top end of what is now known as Oxford Street. In those days it was Furze Hurst, referred to by the locals as “Vuzzy Urst”. It seems to me almost sacrilege to call it Oxford Street. From here Dad was running a milk round in and around Cowes.

Early in the Great War he volunteered for the army and spent the whole of the war in the Royal Artillery, a horse regiment; it suited him as he was always a lover of horses. He had already “broken in” several for himself and others.

While Dad was overseas Mother and I lived in a little terraced house in Pyle Street, Newport. Times must have been hard for a young wife alone with a youngster to bring up. I was born in May 1914. A squaddie’s wages weren’t much in those days – a shilling a day. I can just remember going with Mother to the shops to queue for food. Another memory is of the two of us sitting with our feet in the gas oven for a bit of warmth.

When Dad was demobilised in 1919, we moved to Pan Manor Cottage, just below the flour mill. He worked for his two uncles until we moved to the mainland in 1922. He enjoyed working with Farmer William; they were kindred spirits.

The cottage we lived in has been mentioned in the Isle of Wight Country Press lately. Being a listed building, it was decided by ‘the powers that be’ to have it restored. At the time of my most recent visit to the Island I went to see it.

My definition of the word ‘restoration’ must differ from that of the restorers. There is no conceivable way that the present structure can be recognised as our old cottage. It must be three or four times larger than the original size. Had it been restored to its original size it would not have been of much practical use, I must admit, whereas now it can be used as offices or something of that sort. In a way that makes sense but what I depreciate is the fact that, in spite of the decision to ‘restore’ and assurances made to the conservationists, such vast deviations occurred. Unfortunately, this seems to be a common occurrence these days. If the powers that be will mislead in such a thing as this who knows what other manipulations go on, and maybe to the detriment of the public they pretend to serve? What has happened to the old adage ‘A man’s word is his bond’? The result is, in this case, we have anything but a cottage. Everyone in Newport must be aware of the cottage to which I refer but the following is how I remember it.

Situated almost under the walls of the old mill it was approached from the Pan-Newport Lane by crossing a wooden bridge over a stream, by the side of which stood a large oak tree. The bridge has now gone but the tree still stands; I wonder if that is listed?

The old mill, now converted to other uses, belonged in those days to Thomas, Gater and Bradfield and was a hive of industry. There was an almost continuous stream of traffic, bringing raw materials and taking away the finished products. There were horse-drawn vehicles, Foden steam wagons and a few solid-tyred, chain driven lorries.

I was friendly with a lad whose father worked in the mill, and we were sometimes allowed to go inside, and it was a never-ending source of wonder. We would marvel at the machines and the activities. The place had, too, an aroma all of its own. We also visited, unofficially I might add, a large shed behind the mill and helped ourselves to locust beans stacked in sacks.

Back to the cottage.

As we came over the wooden bridge to approach the cottage we passed on our right, a two-horse stable, by the side of which was an open cart shed. This latter housed our dog cart, ralli cart and wagonette. In the stable was kept our little dun pony. Joe, and Tit, a fourteen hands mare.

Often, we had a ride out into the countryside on a Sunday afternoon, taking our tea and eating it in the corner of someone’s field. Sometimes we got as far as Sandown or some other spot by the sea. Dad bought Tit, the mare, from a hunting stable and she, too, took us on many very enjoyable trips. She really picked her feet up and Dad would say, “she bloomin near steps through her collar”.

I saw my first pig-killing behind that stable. I remember it was a bit gruesome, but we were recompensed by fresh pork, salt pork, faggots and chitterlings – known to us as chidluns. There was also of course, liver, lights, kidneys and trotters; the brawn made from the pig’s head was out of this world.

Behind the stable was quite a large garden and, beyond, the withy beds. Greta Granpa Rose – who was by then an old man – a lovely old chap – used to potter in the garden and was sometimes joined by another old gent, Mr Smith. He lived a little further down the road towards Newport where he and his sons ran an agricultural engineering business – although I think, then, that the old chap must have been retired.

The cottage, small and square, stood on the left of a widish gravelled area. The ceilings were very low; in fact, my Mother, when brushing her long, wavy tresses, touched them. Fortunately, my Father wasn’t very tall so the low ceilings didn’t bother him. An old mangle stood outside the back door and a galvanised bath hung on a nail nearby. Also on the wall was a perforated zinc food safe. There were no fridges or freezers in those days. My brother, Harold, who has been in Australia for thirty odd years and our sister, Maisie, sadly no longer with us, were born in that cottage. Harold, who was on a recent visit to us, was of a similar opinion to me regarding the restoration.

If one continued past the cottage and over another small stream, one came to a large, very old house which has since disappeared. Living there was a delightful old couple, Mr and Mrs Turner. I often trotted over to see them and the old lady used to call me “Little Breaches”. Their two sons, Reg and Clive ran a market garden there and watercress beds. The area was intersected by small streams which ran down to connect up with the main river in front of the Shoulder of Mutton, just by the old stone bridge.

During the time we lived at the cottage my Grandparents, on Dad’s side, Harry and Ada, lived at Fairlea. Old Granpa Rose lived with them. They were a great couple. Our lives became more involved when we came to Highbridge.

Harry was running the milk rounds from Great Pan Farm at the time of which I write. Their middle son, Herb, who served in the Navy during the Great War – and was an engine room artificer – married young Flo Shepherd. Her parents had a bakers and confectioners’ business in the Square and were well known for, among other things, their doughnuts and salt lardy cakes. — and, talking of food – another shop we patronised was Hales’ the pork butchers. They sold the most delicious pork scraps you ever tasted. After going over to the mainland, we paid occasional visits to the Island and invariably came back with doughnuts, salt lardy cakes and pork scraps.

Uncle Herb and Aunt Flo moved to Eastleigh, on the mainland, in 1920, two years before us. The younger brother, Bern, was employed for some years by Crouchers, the importers and exporters on Newport’s Town Quay. He married a Londoner, Una Frances. She was, at first, a teacher at Barton Village School, where I started school. She later became a relief head mistress, travelling to many parts of the Island.

The boys’ sister, Nessie, the youngest of the family and nine years my senior, worked in Dabells, the drapers in High Street. She came with us to Highbridge, and she and I had great times together. She is now married to her third husband, a retired Australian sheep farmer and lives near her son, David.

Being involved in the farming community I often accompanied Dad and/or Farmer William to the market in Newport Square. Iron railings lined each side of the Square to which were tethered horses, ponies, cows, bulls, etc. Those rails were only about four feet away from the shop fronts and so, at times, when passing an extra fierce looking bull, one did so with a certain amount of trepidation. Invariably I would be encouraged by “Come on, Nipper, ‘e won’t eat ya”.

The sheep were penned in hazel hurdles in the middle of the Square. There were always plenty of folk milling around, the sightseers in their town clothes easily distinguishable from the visiting country folk in their broadcloth suits and gaiters; I can still her snatches of conversation in the local dialect; “Ow be you, Jarge? Ow’s yer taters doin?” “That ere bull looks a vierce un. Oi would’n want one o’ they ‘orns up my backside”. Or “Ows yer missus?” “Ah sne’m a bit unner the weather, sno. Last night she shivered and shook like a dawg in a wet zack”.

Hampshire dialect is somewhat similar to that of the Island but there are some words and expressions essentially Isle o’ Wight. Even after all the intervening years I am still sometimes recognised by some as an Isle o’ Wighter.

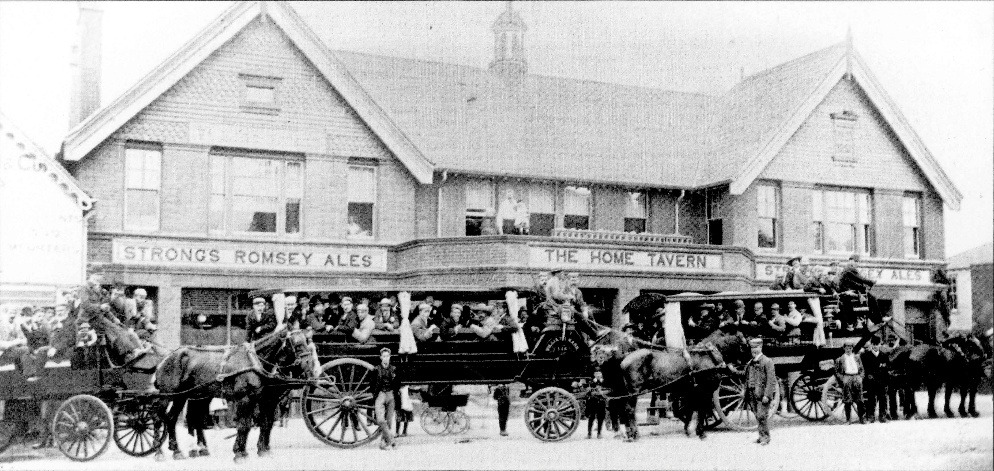

After coming over to Highbridge Grandpa, Dad and I sometimes went back to Newport market or a farm sale. This was always exciting for me. We would drive down to Southampton in the pony and trap which we left in the charge of the little old ostler at the Haymarket Inn. This was almost opposite Edwin Jones’s store or, as it is now, Debenhams. We them boarded one of the old paddle steamers and then breakfasted down below. I can still smell the bacon and see the green water as it rushed past the portholes.

Reverting to the time we lived at the cottage – Mother liked to go to visit her folk at Cowes occasionally. Dad would sometimes run us down in the trap but, if he was busy, we would walk. On a couple of these jaunts – five miles each way – I rode my wooden wheeled scooter. I must have been six or seven years old then because it was before Harold and Maisie were born. We would go up Honey Hill and Horsebridge Hill, past the old St Mary’s Hospital on our right, and the prison on our left; passing the Stag Inn on our right we were soon in open country. We could look away to our right and see the ribbon of the Medina River as it wound its way to Cowes and the sea. It is a tidal river so that, at times, it is not much more than a trickle between the mud banks. On the near bank, in an area of white dust, stood the cement mills with its own railway halt. Further on our way we passed the Horseshoe Inn and then, not far away, the Flower Pot Inn. This latter pub was distinguished by an ordinary flowerpot on top of about a thirty feet high pole. It always struck me as looking ridiculous. I must have had some sense of proportion even in those days. I seem to remember all the pubs en route although neither Dad nor I ever went in one.

Next of note, on the site of what was to become Somerton Airfield, stood the motor-scooter works. You may remember the Lambretta and similar motorised scooters that came into their own and became popular worldwide. At the motor scooter works these were invented about thirty or more years earlier but seemed to be before their time. The pubic weren’t ready for them and the business collapsed. Had they been just a few years later when the public were becoming more – cheaply – travel minded those pioneers would have enjoyed a resounding success.

Continuing on our journey it was a long downhill run past the cemetery, and we were at our destination. On our return journey it must have been a great relief to my little fat legs to free wheel on my (unmotorised) scooter down Horsebridge and Honey Hills. We seldom did the trip by train; I expect funds were a bit low.

Both before and after coming to the mainland I often spent holidays at Arctic Road. Grandma Allen was a lovely person. She was not my real grandma but the only one I knew – on my Mother’s side. My Mother lost her Mother when she – my Mum – was fifteen years old. After some years Grandpa married Martha, and she was held in deep affection by all who knew her. Mother had an older brother, Lewes, and a younger sister, Nellie. Lewes was married to Annie Souter, and they had four children, Charlie, Don, Mollie, and Syd. Uncle Lewes was an exceptionally clever man. He was of some repute on the Island as an artist. He was also a competent motor and radio mechanic and, indeed, could turn his hand to almost any job; the more difficult it was, the greater the challenge. Like many clever people he was somewhat eccentric and not always easy to live with, but I was quite fond of him; Aunt Annie was a kind loving soul, loved by all. The family lived in Wyatts Lane, Northwood before moving out to Wroxall where Uncle built a bungalow; he did everything except connect up to the services. The whole family was co-opted into the building process – or perhaps I should say, coerced.

The three boys served in the armed forces, Charlie in the navy, Don in the marines and Syd in the army. They all finished their working lives as warders in Parkhurst Prison. Mollie was involved in various activities mostly with the church and was, for years, an officer in the Girl Guides. She later married Ernest King who was rector of Whippingham Church. This was where Queen Victoria attended when staying at Osborne House.

Mother’s sister, Nellie, was a Great War G.I. bride. She married Cecil Kittle who had emigrated to the U.S.A. and returned with the American forces. He and his family of six were staunch Salvationists.

When holidaying at Arctic Road I often went walking with Grandpa Allen, mostly by the sea. During Cowes week he would explain where the yachts were going and how the rigging was used and why. Being an old seaman he was a mine of information. In those days racing was between the big yachts – King George the fifth’s Brittania; Tommy Lipton’s Shamrock; Tommy Sopwith’s Endeavour, Moonbeam, Velsheda and others. Grandpa also introduced me to Captain Upstall under whom he had served many years previously. They wore white-topped peaked caps and, on these jaunts, so did I. I thought I was the cat’s whiskers. Old Captain Upstall always addressed me as Cap’n.

To get to the sea our walk would take us down over Shooters Hill and along the High Street. This was very narrow and even in those days, could be very busy with traffic trying to pass each other – mostly horse-drawn, of course. The High Street housed several ships chandlers and a shop that always fascinated me was a taxidermist. There displayed was a calf with two heads, a pig with five legs and many other freaks from the bird and animal world. All were interesting, some slightly frightening and some downright repulsive. However, I was irresistibly drawn to them.

Further on we passed the Fountain Inn and the Pontoon where the paddle boats dropped and picked up passengers and freight. The steamers didn’t go over to East Cowes as now. (If I remember rightly the return fare to and from Southampton was one shilling and ninepence).

A little further along, on the sea side was the old sail loft where Ratsey and Lapthorns, the world-renowned sail makers, plied their trade. Grandpa’s father used to work there in about the eighteen fifties. It is now an excellent Maritime Museum.

On the opposite side was Morgans, the sailing worlds outfitters. Grandpa, during his service with the Empress Eugenie, had his uniforms made there. Sometimes he did not need the full quota to which he was entitled, so Mother and Nellie were fitted out with some of the very best overcoats. They thought they were some of the best dressed youngsters in Cowes.

Now it was down Watch House Lane and the sea. It was at the slipway at the bottom of this lane that the two girls used to wait for their father when he returned from his trips at sea. I remember seeing the large seaman’s ‘frail’ basket in which he used to bring home the bits and pieces from foreign parts. How these girls must have waited in anticipation to see what Dad had brought!

The Parade was, as its name suggests, where all classes of people strolled leisurely along, to see and be seen. There was once a pier, but that has since disappeared. On the landward side of the Parade were several hotels including the Gloster and the Globe. In later years another was built, a huge white monstrosity, surely one of Prince Charles’s carbuncles. It is an eyesore to anyone walking by and an even greater source of disgust to anyone approaching from seaward. To my mind, and I am sure, to countless others, it was a ghastly mistake.

I have often enjoyed firework night on the Parade. In the darkness the milling crowds would be bubbling with anticipation. At a given signal all the hundreds of vessels, large and small, would light up overall with coloured lights. All the following firework displays were reflected in the water. It was a magnificent sight. In those days half the Island turned up but there were very few cars. The ponies and traps, wagonettes, dog carts and gigs were tethered alongside all the roads leading to the sea.

Beyond the Parade stood Cowes Castle, the home of the Royal Yacht Squadron, the world’s most prestigious yacht club. Alongside was the Royal landing jetty. The steam yacht, Victoria and Albert, was anchored in the Roads and I’ve often been standing by the jetty and could almost have touched, as they came ashore, King George and his queen, Mary; the Prince of Wales (who later abdicated as King); Princess Mary and other members of their entourage. I can still smell the nearby seaweed and see the row of brass cannon under the squadron’s walls.

Just around the bend from the building one approached Princess Green and the first stretch of beach. In a corner of the Green stood the umbrella tree and, nearby, a nice drinking fountain. The latter was quite elaborate and had on it a quotation from St. John, chapter 4, verses 13 and 14. It says ‘whoso drinketh of this water shall thirst again but whoso drinketh of the water that I shall give him shall never thirst’. Beyond the Green was Egypt Point with its small lighthouse and lions on their stone plinths. In those days the road ended here and the only way to proceed to Gurnard was along the sea edge where the sloping banks were covered in gorse, blackberry bushes and scrub. The going could be very difficult owing to a large area of blue slipper clay. When, later, the council decided to build a road to connect The Green to Gurnard, Grandpa, who had known this area from a small boy, warned that it would always be a source of trouble and, even to this day, the winter storms and seas undermine it, and extensive and expensive repairs are necessary almost annually.

At the very start of the walk from Arctic Road I have previously described, we passed the road that led to the floating bridge that connected West Cowes with East Cowes on opposite sides of the River Medina. If it was knocking off time in the shipyards the roads would be choked with the workers in their overalls and cloth caps and the foremen in their bowler hats as they made their way to their homes. The fare over the bridge was one penny. I remember crossing on several occasions as we went to see The Shell House, Osborne House and Swiss Cottage.

When we final left the Island in 1922 we came down from Newport bringing with us about twenty cows, as we were bringing them to our – and their – new home on the mainland. In the lead was the pony and trap in the back of which was a calf. The mother followed, naturally and, in turn, the others followed on behind. After a few deviations into gateways and gardens they settled down and plodded quietly along.

At Cowes we boarded the freight paddle boat, the Lord Elgin, and disembarked at Southampton. We then made our way up through the High Street, under the Bargate, past what is now Eastleigh Airport, through Eastleigh and out to the farm. This was about seven miles from Southampton. By this time there was little liveliness in the cows or even in those that accompanied them, and they soon settled down in their new surroundings. —- but this is the beginning of another story.

P.S. Grandpa (Harry) farmed at Highbridge for about thirty years and Dad (Reg) farmed at Breach Farm, Bishopstoke, for about thirty-two years.

(Harry Morris at Highbridge Farm)

Cowes Regatta

Memories of seventy-five, or more, years ago

It is now mid-September, but I am sure you can remember having seen on television and read in the newspapers of this year’s happenings at Cowes regatta. How very different from those of my boyhood days!

Cowes High Street shops are almost unaltered except that they now show and sell goods more attuned to modern times. One especially springs to mind. Gone is the little old taxidermists that used to fascinate and even frighten me. In the dusty window that looked as if it hadn’t been disturbed for years was a calf with two heads, a pig with five legs and many other monstrosities. The proprietor, hovering in the dim interior, only added to the fascination. He was probably as old as the animals in his collection. I think it has been replaced by an ice cream parlour. I don’t think I could fancy an ice cream from there. Ugh!

Two other of the old establishments are still in the street: Atkeys, the ship’s chandlers and Morgans, and Morgans, the yachting fraternity clothing outfitters. Morgans used to supply uniforms for the various yachts, one of which was The Thistle. She was home of the widow of Napoleon the Third of France – the ex – Empress Eugenie. My Grandfather served on her yacht for a number of years. When he didn’t need a new uniform my Mother and her sister were some of the best dressed youngsters in Cowes. Morgans now sell shirts and jumpers with motifs and logos to suit the young yachtsmen of today.

When I walk along the High Street now, I experience a certain sadness. I know that progress is inevitable but so much, t seems, is lost in the process. I suppose, in some ways it is better so, and I refer now to the fact that yacht racing is no longer the prerogative of the privileged few but can be enjoyed by so many more, obviously in a humbler way, but non – the – less enjoyable.

At the time of which I am writing we lived just outside Newport. My maternal Grandparents lived in Cowes, and we would often visit them, certainly during Cowes week. My Grandfather, being an old seaman of the sailing ship days, would explain the comings and goings of the large yachts and this, to a young whippersnapper was most interesting. We would walk along the Parade, he wearing his white – topped peak cap and me, in similar rig, as proud as a peacock.

We walked from Arctic Road, past the Rope Walk and some of the shipyards, down Shooters Hill and into the High Street. There were very few motor vehicles. The other traffic was all horse drawn – butcher’s and baker’s carts, milk floats, a brewer’s dray and once, I remember, a hearse. The narrowness of the street often caused mayhem as they tried to pass each other.

Opposite Atkeys, to which I referred, was the entrance to the Pontoon. All the cross – Solent ferries – all paddle boats, belonging to the Isle of Wight Steam Packet Co. used to tie up at the Pontoon. They didn’t go to East Cowes, as they do now. We continued along the High Street almost to the end then tuned right down the narrow Watch House Lane to the sea and the beginning of the Parade. There were, on the landward side, restaurants and hotels, all dressed in bunting and flags of several nations. Halfway along stood the pier where the excursion boats tied up; that has now disappeared.

At the far end of the Parade was, and still is, Cowes Caste. This was home of the Royal Yacht Squadron Sailing Club, one of the most select in the world. During this week large yachts were anchored in Cowes Roads, the most prodigious being the Victoria and Albert, the home, for this week, of the Royal family.

I have several times stood close to the Royale Slipway where brass-funnelled pinnacles brought the Royals and their friends ashore. I could have reached out and touched King George the Fifth, his Queen, Mary, Princess Mary (who later became The Princess Royal), Edward, Prince of Wales (later Edward the Eighth who abdicated his throne) and his younger brothers. It was a thrill to me.

The Castle grounds had marquees and canvas-covered awnings where the guests could sit and chat. The row of brass cannons that stood on a platform near the sea signalled the start of the races; they still do.

In those days they were for a very different class of yacht. They were large sea-going vessels with acres of sails and were a magnificent sight. There was the King’s Brittania, Tommy Lipton’s Shamrock, Tommy Sopwith’s Moonbeam, Velsheda and others. They made a thrilling sight when ploughing through, sometimes, rough seas with their large sails and spinnakers billowing in the wind.

All this was very exciting to a young lad, but I think the climax was something that half the Island looked forward to; Friday – Fireworks night. The Parade would be packed solid and, as it began to get dark, the excitement was intense. As the darkness deepened all lights were extinguished and then, suddenly, as one of the brass cannon boomed out, all the boats, large and small, were illuminated overall. Their reflection in the water was breathtaking. The fireworks continued for some time. The grand finale, however, was the highlight. It was a set piece depicting the King and Queen, while underneath were the words, “God Save the King”.

Imagine what it was like when the excitement died down and everyone decided to make for home. All the roads leading up from the sea were lined with vehicles of all types – traps, wagonettes carts, brakes, landaus etc. The horses’ heads were tied to gates, fences and even to heavy weights.

Mother, Dad and I made our way back to Arctic Road where Dad had tethered our pony, Joe, and the trap. After a sup and a bite, we rattled off back to Newport over the gravelled road, the only lights being from the candles in the carriage lamps and the occasional sparks from the pony’s shoes and the iron-shod wheels.

These are some of my earliest recollections of Cowes Regatta and ones that will always remain with me.

The Haymarket

Southampton

We came over from the Isle of Wight in 1922, when I was eight years old, and went to live at Highbridge Farm, three miles out of Eastleigh.

In those days the shopping facilities were pretty basic and if we wanted to purchase anything special, we had to go to Southampton to do so.

There was, at that time, no bus service from Highbridge to Eastleigh so we had to resort to pony and trap – or walk. Dad would sometimes take Mother to Eastleigh station in the early afternoon where she would catch a train downtown. Later, when the afternoon milking had been done, we’d, as Dad would say, “Catch a bit of tea” and then harness up the little dun pony – or Tit, the sleek brown mare and off we’d go at a brisk trot.

We’d rattle down through Southampton – taking care to avoid getting the trap wheels caught in the tram lines – and drive into the yard of the Haymarket. The yard was of cobbles and, to one side was an open shed where we parked the trap while, on the other side was stabling where, for a shilling, we would tie the horse and leave him for the evening. That shilling also provided a feed of hay and a bit of straw underfoot.

There was, in attendance a little old man who would touch the peak of his old cloth cap and assure us that “he’d keep an eye on t’oss for us.”

Dad and I would then go and meet Mother at a prearranged place, return to the Haymarket with her purchases and put them under a blanket in the trap. There was no need, in those days, to put things under lock and key.

Then came what was tom me the thrilling part; we’d meander up through East Street where the crowds were so dense one could have walked on the heads of people. What a cosmopolitan crowd they were. There were all nationalities and colours – Turks, Lascars, Indians, Chinese etc. and what a babble they made as they chatted and bargained with the shopkeepers!

Many of the goods for sale were displayed outside the shop fronts and the salesmen would offer all sorts of inducements to buy. If you bought a suit for thirty-five shillings (£1.75) they would throw in a watch or a pair of shoes.

Close to the Horse and Groom was a hot chestnut barrow where one could buy a bagful for twopence. Up at the top of East Street was Samuels, the jewellers on one corner and, on the other, on the pavement by the old church, was a pavement artist displaying his work. He fascinated me, not because of his paintings but because he had no legs and used to propel himself along on a little board. I always had instructions not to stare but I’m afraid I always did so.

We then made our way up to the Hippodrome in Ogle Street, armed with the remainder of the chestnuts and perhaps a bag of monkey nuts as well. There were some marvellous shows there and I remember some of the names of the artists, G.H. Elliot, Randall Sutton and others.

Afterwards we’d meander back through the crowds to where Joe – or Tit – would be patiently waiting. He would whinny a welcome and soon we’d be rattling over the cobbles and all set for the run home; but not before the old ostler’s hand had closed over the extra tanner we’d given him. I never knew his name, but he was a kindly old gent.

Up under the Bargate we’d go at a brisk trot, and it wasn’t long before we were out in the dark countryside with only the carriage lamps to help us see our way. Dad’s eyes were good, and Joe knew his way home, anyway.

Mum and Dad would be sitting up front with a rug tucked round their knees while I’d be tucked up cosily in the back. We used to sing all the old songs as we journeyed and, I’m sure, some of the new ones we’d just learned at the Hipp. A cup of cocoa, perhaps a bacon sandwich and then off up the wooden hill.

It had been a thrilling day for a lad of eight, nine or ten and, as I think of it now, I can still see the old Haymarket as clear as ever.

Breach Farm

Bishopstoke

During a recent conversation the name Breach Farm was mentioned, and I was asked by a comparative newcomer to the area if I knew anything about it. It only occurred to me that, except for the older residents of the village, Breach Farm was just a place that had come to be noticed when Hall and Sons, the gravel and aggregate firm, excavated thousands of tons of these materials from part of the land.

(Harry, Reg and George Morris at Breach Farm)

The place gained notoriety because of the excessive amount of heavy traffic involved in the transport of the materials. This traffic caused mayhem on the roads with mud and stones and, even more, by the vibrations which not only tended to ruin the road surfaces but disturbed the foundations on the other side of the road. As a consequence, the name Breach Farm became synonymous with inconvenience, discomfort and just plain nuisance.

That this has now disappeared with the cessation of gravel extraction and the area has now returned to the peace and quietness of its previous existence must be a source of satisfaction to so many of the local residents.

(Breach Farm from across the water meadows, Bishopstoke)

This was a decidedly different Breach Farm from what I knew from about 1930 onwards when my family lived there and my Father farmed the area. The family – Father, Mother, my brother Harold and sister Maisie moved into the house in 1930, and I joined them a year later when I returned from a period of farm work in Alberta, Canada.

Breach Farm was originally, I understand, part of the Mount estate and at one time belonged to a Mr. Hargreaves. My wife’s late mother remembered him driving around the village in a four-in-hand. The house was rebuilt in 1892 by the next owner, Mr. Thomas Cotton. He resided there for some years and after his decease it was converted into a Sanitorium and several more buildings were added.

Mr. Cotton was a much-travelled man and was a keen arboriculturist. As a consequence, there were, in his extensive grounds and gardens, many foreign trees, shrubs and plants. Prior to the walkabouts of the recuperating hospital patients, each tree and shrub had a label giving its name and country of origin. Unfortunately, vandalism existed even in those days and those labels were either removed altogether or mixed up causing much confusion.

The grounds sloped down quite steeply to the banks of the River Itchen. A series of stone steps were constructed here, and they were adorned on either side by ornamental urns and figures of birds.

(The Mount Steps)

There was a large aviary near the house, and, on occasions, all was thrown open to the public. As can be imagined, all this necessitated a large work force and, at one time, there were sixteen gardeners and other outdoor staff employed there.

The main gates were-and still are- situated above the old school and almost opposite St. Mary’s Church. This was not the official entrance to the farm, but we were permitted to use it when going to the village or to Eastleigh. Our official way in was at the top of the hill between the Doctor’s house and a large spinney of trees.

This has now been sealed off. When the gravel excavations started a new way in was opened up, presumably to avoid damage to the house. The Doctors House was so called because it was the residence of the doctor in charge of the Sanitorium. Our road in was called the Cinder Track because that is, in fact, what it really was. It was resurfaced annually by loads of cinders fetched from the Running sheds of the railway works at Eastleigh.

At the bottom of the first slope, it met the other road which came from the main gates, through between the hospital buildings, past two gardeners’ cottages, the clock tower, workshops and mortuary. Where these two roads met was a notice board which warned recuperating patients from the hospital that this was the limit to which they were allowed to go in that direction. Consequently, this was known to us as “Out of Bounds Corner”.

(Aerial view of “Out of Bounds Corner” and track to Breach Farm on the right)

(Out of Bounds Corner at ground level with Clock Tower and cottages on the right)

Coming down the Cinder Track to this point, Hospital Ground was on our left and the top ground was on our right. Each of these fields had one or two fine spinneys of trees. These could be a nuisance when engaged in the various cultivations but provided good shelter for cattle and certainly enhanced the beauty of the scene.

Before leaving the environs of the hospital I should mention that these were converted and added to cater for the sufferers of tuberculosis, or consumption as it was commonly known, in the late twenties. This complaint was then rife. Often, both day and night, when passing through, we would often meet the hospital porter pushing his trolley along with another customer for the mortuary. The local St Mary’s Churchyard was fast filling and so a rule was made that, unless the deceased was a local person they were not allowed burial there. In those early days there were often eight or nine deaths a week but as progress in the research of this complaint was made, and also by the dedication of Dr and Mrs Capes – she was also a doctor – it became cause for comment if one saw Mr Keresen with his grim burden.

On leaving Out of Bounds Corner to continue to the farmhouse, the hospital gardens and piggeries were on our left; all of these supplied food for the patients. This straight stretch of lane was, at this point, lined on the right, by a large number of oak trees and a strip of hazel coppice. These had a beauty at all times of the year and, in Spring this was enhanced by a carpet of primroses, bluebells, anemones, Soloman’s seal, red and white campions etc.

The lane then made a right-hand bend – known as Piggery Corner and on this bend was a holly tree. This, in its season produced a profusion of berries of which we made good use at Christmas. Most of the oaks and all of the hazel has now been replaced by a wire fence, I call this an act of vandalism but am told it is progress. I’ afraid I can’t be convinced.

Now, on our left the land fell sharply away to the water meadow below. These slopes were, at first, all brambles and scrub but were replanted with larch, poplar etc. These grew and have since degenerated and no use was ever made of them. Now all is a tangled mess again. Here in the undergrowth, there were the usual woodland flowers, interspersed, quite prolifically, with daffodils and narcissi etc. presumably thrown out by the Mounts gardeners.

The last part of the lane before reaching the farm buildings and house was down a steep slope, probably of about four or five in one. This was of shingle and pebbles. In wet weather this packed down hard but in dry spells it became very loose and often caused problems when attempting to traverse it with a loaded cart or lorry. Indeed, it was hard going to walk on such a surface.

The wooded area to which I previously referred continued on the left, down the hill and was known as Breach Copse.

The farmhouse stood almost at the bottom of the slope on the left-hand side. It was, from the outside, a somewhat unprepossessing building, plain, rectangular and with, though this may sound contradictory, the front and back doors on the upper side, by the road. There were no doors on the lower side as the ground fell sharply away and then levelled out to form our garden. It was a six-roomed house, three up and three down and very basic. In later years a bathroom, toilet and larder etc. was added and this made a considerable difference. Our original toilet, known as the dunniken – or simply the ‘ouse, was a wooden structure situated at the bottom of the garden and the bucket therein had to be emptied periodically. The contents were dug into a hole further down and we were always proud of the marrows we grew there. Our new flush toilet was, undoubtedly, an improvement and we considered it progress, but we never grew such good marrows again.

(A dilapidated Breach Farm showing the steep sloped track)

I don’t know the age of the house, but it was said to be two hundred years, at least, and was to me, something of a marvel. Although built on slopes going two ways, both length and width wise, it had absolutely no foundations. This was discovered after the last war when repairs had to be carried out to the wall on the lower side because of damage caused by the vibration from bomb and gunfire blast. When the repairs were carried out new foundations were laid but the remainder of the house still stood on bare earth. During very wet weather water would rush down the hill past the house but never disturbed it.

When we arrived at the farm the house had not been lived in for a number of years. Prior to our tenancy it had been farmed by Mr Charlie Neale, of Hill Farm, Brambridge and, before that, by a Mr Hurtes and I have read that he supplied milk to much of the village. It was then owned by Hants County Council. My paternal Grandfather farmed it for some years in conjunction with Highbridge Farm on the other side of the river.

(Pictures of Breach Farmhouse taken during a survey in 1948)

In our early days there, Father and I worked for him but, later, when Grandfather relinquished the tenancy, Dad took it over. Still later, a few years before he retired, he bought the place.

When we moved into the house it needed some attention indoors, but it wasn’t until some years later that the extension to which I referred was added. This, with a connection to the mains water supply, the installation of a Rayburn cooker, electricity and a few other odds and ends made life much easier, especially for my Mother. How she coped in those earlier days I don’t know and, sometimes, I don’t think she did, either.

In the winter she cooked on an old kitchen range. Depending on the way of the wind and the airless dense fogs which often persisted in this low-lying area, the fire wouldn’t draw, the room filled with smoke and the flues needed frequent attention.

In the summer she cooked on a three-burner oil stove and when I think of the meals she produced under such conditions, I marvel.

We, as a family, were hearty eaters but always there was plenty of good wholesome food. She baked her own bread for years until, during a long illness, we were supplied by Mr C.N. George, generally referred to as C.N. She occasionally baked bread again but not regularly. Thursday was bread-baking day, and I can still savour the aroma. Hot cottage loaves, straight from the oven, with lashings of her own butter is something I shall never forget.

Prior to being on the mains water supply our water came from a spring up in the field opposite the house. It was always clear and cool. The elevation enabled us to have a tap over the sink. The cattle also drank from the spring. Farm work can, at times, be very dirty and baths could be a bit of a problem, especially in hot weather. We used an old, galvanised bath which, between usages, always hung on a nail outside the back door.

Until the installation of the Rayburn, heating the water was quite a chore but we managed to keep clean. I wonder what the young folk of today would think of these conditions.

One thing I have not mentioned is lighting. We used paraffin lamps and, to go to bed, candles. Often, we went up in the dark. We advanced to an Alladin lamp and then to a Primus, all improvements, but when the electricity was installed, we seemed to be living in a different world.

Opposite the house, on the right of the road, the bank sloped steeply to the field above and was clad in trees and bushes etc. These were overshadowed by a large oak tree. At various times of the year these all added to the natural beauty of the place.

Over the years the weather had washed out much soil from under and around the roots of the oak and the hole provided a kennel for the succession of dogs we had; there was Terry, the Springer spaniel; he could be quite fierce but was a splendid house dog. Most of us didn’t trust him but my wife – she was then only my girlfriend – got on famously with him. She would adorn his neck and head with daisy chains, and he loved it. Then there was a scruffy little gingery-haired terrier. He also let us know when anyone was approaching over the top of the hill. These dogs were on a long running wire that allowed them to go up beyond the back door and woebetide any strangers who ventured too close. Old Bess, the blue-black spaniel bitch was everybody’s favourite. She had a lovely disposition and accompanied us when working all day in the fields and water meadow. Over the years there were other dogs, all of whom seemed to be part of farm life.

Now, leaving the house we descended to the farmyard. This was a rectangular area, bounded on the right hand by a galvanised iron fence and on the left by the small dairy and cow stable, this latter was a slate roofed building and accommodated eighteen cows. We laid a four-foot-wide concrete pathway along the front of it, and this enabled us to keep much of mud away from the building. This, together with the stable, was scrubbed daily.

(Reginald and Harold Morris milking at Breach Farm)

In those early days the milk had to be delivered twice daily to James Hann and Sons, Eastleigh by pony and float. Later a cooler was installed, and a lorry collected the milk once daily.

At first, when the two farms were run as one, the cows were brought over from Highbridge as and when the supply of grass and feed was available. We used to bring them via Brambridge, round the lanes, up through Stoke Common and down the Cinder track. Later, a wooden bridge was built over the river, by Houghtons of Durley. This made for much easier and less time-consuming movement from farm to farm. Eventually, when my Grandfather relinquished the tenancy of Breach, Dad took it over and it was run as a separate entity.

He started off with a nucleus of young in-calf heifers, shorthorns, which he purchased from Mr Frearson of Twyford Farm. Over the years he switched to guernseys, and this enabled him, because of the increased butter-fat content of the milk, to qualify for a subsidy of four pence per gallon, this was followed by a further subsidy of four pence when he qualified by passing tuberculin-free tests. This, needless to say, boosted his monthly milk cheque.

At first, we did, as had been done for generations before, milked by hand. A machine was then installed, and life seemed to be that much easier. The power for this was supplied by a little Petters engine situated in a lean-to attached to the lower end of the stable. This shed also housed cattle, pig and poultry food.

The far end of the yard was bounded by a large barn.

(Buildings on Breach Farm photographed for a survey in 1948)

This did not present the most pleasing appearance as it was painted black corrugated iron. The structure of its timbers, however, was quite remarkable. They were large, solid beams which, at some time in their existence, had been ships timbers. It was possible to see where the previous joins had been made. No nails or screws had been used; all being held together by dowelling. This barn had numerous uses, sometimes being filled to the roof with hay, mangolds, swedes etc. stored for winter feed. At other times it contained machinery, and the thousand and one bits and pieces always found on a farm.

The bull pen was attached where Breach Duke pawed the ground, snorted and from where he was brought forth to do his bit toward the running of the farm.

(Harold Morris pictured with Breach Duke)

A gate on the right-hand side of the yard opened out into Home Paddock where was situated the aforementioned spring and the deep litter poultry houses. The other gate, in the lower left had corner, led to the water meadow.

(Reginald Morris feeding poultry at Breach Farm)

This meadow, though labour intensive, was a valuable source of supply of fresh young grass for the cattle. By a method of irrigation, which I have described elsewhere, a good supply of early feed in the Spring boosted the milk yield and again when the higher meadows were burned brown by the summer sun.

In those days there were such meadows stretching the length of the Itchen. I had practical experience of them from Highbridge, through Breach and Withey meadows – now owned by my son and his wife, – the fields which now form Eastleigh Playing Fields and those south of the Bishopstoke Road and down as far as Six Arches, where the Botley railway line spans the river.

(River Itchen with Breach Farm in the background)

My brother Harold and I are the last remaining of the old workers – known as drowners, to have worked in these meadows. The Beeden family of Stoke Common had worked these areas all their lives but, sadly are no longer with us. Indeed, they taught us the intricacies of this work when we first came over from the Isle of Wight in 1922, we having had no experience in this line.

(Water meadows pictured during a survey in 1948)

Most of these meadows have now been levelled and drained and treated to get rid of weeds, sedge and reeds etc. and by the use of artificial manures, they still yield well. However, I have never since seen almost knee-deep areas of young green grasses and herbs that gave the cows – and us workers such pleasure and satisfaction. The work was often long, arduous, cold and wet but of great interest and I enjoyed my work there.

An aspect that saddens me is that, with the use of herbicides, many plants and flowers have been lost – marsh marigolds or, as we knew them – king cups – water avens or, as we called them, granny bonnets, forget-me-nots and many and many of the attractive reeds and rushes. There were also valuable herbs which the cattle knew and ate. I wonder if antibiotics and other man-made substances can ever really replace those natural additions to the cows’ diet?

By the rivers some of these flowers still remain – the yellow irises with their sunny blooms, purple loosestrife, blue and white comfrey, etc. Due to some pollution of the waters much of the broad-leafed, semi bitter watercress has disappeared. The cultivated varieties now available bear little resemblance to the natural kinds. How we used to enjoy feeds of that plant and, as Father would say, “it does yer internal workin’s a power of good”.

Talking in this vein reminds me of the old remedies that we used to cure aches and pains – a swede cut up overnight and soaked in brown sugar, good for coughs; brimstone and treacle, made with flowers of syrup and treacle, helped if we were bothered with constipation; a bowl of boiled onions laced with pepper or a basin of bread and milk laced with black treacle would bring out a sweat that would get rid of any cold. Dad also believed that some of which would cure complaints in horse or cow was good for humans. Polienta oil, used on cattle was rubbed into a tight chest; Tipper’s cow relief, a Vaseline-like substance, was excellent for chapped hands. Old Mr Beeden, when having cut his hand when whetting his scythe or his hay knife, would come into the stable and collect cobwebs to wrap around the wound. These would stop the bleeding and sure enough, healing would take place quickly and cleanly. The leaves of plantain would have a similar effect. Back ache, often caused by unaccustomed exercise, was relieved by applying a hot iron to the affected part.

I can assure you that I have tried, not always willingly, all of these nostrums but must admit they haven’t always produced a cure but, undoubtedly have brought some relief. Other things which benefitted one’s health, and which were accepted with much more willingness were blackberries, elderberries, both of which made excellent tarts, jams and jellies. Crab apples made a wonderfully piquant jelly and field mushrooms were eagerly looked forward to on those warm, misty September mornings.

(Water meadows with Breach Farm in the background)

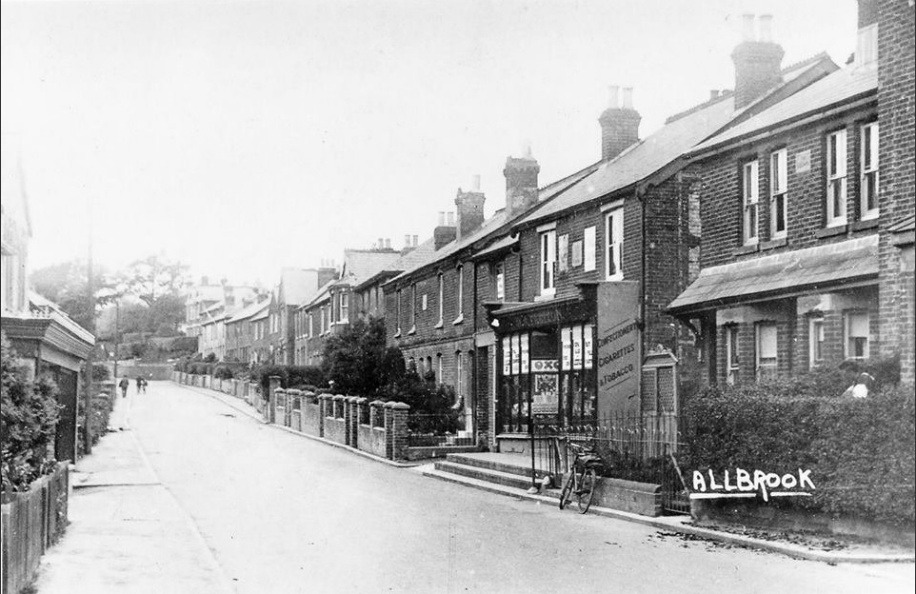

Having turned right out of the water meadow – or walked through the barn – one had a clear view across the twenty-one-acre field and across the river to the railway line. Beyond one could see the houses of Allbrook village as they clad the hill leading to Eastleigh. To the north was a view up the valley toward Winchester. High up one could see Otterbourne Grange among the trees, the home of Mrs Fitzgerald who, I believe, was the aunt of the famed naturalist, Brian-Vesey Fitzgerald.

I’ve seen this field under several crops – mangolds, swedes, turnips, kale, oats and hay. Being very gravelly I remember quite vividly the back breaking work when hoeing them. Even when horse-hoeing the stones made progress difficult. However, some good crops were grown there.

The machines for harvesting the hay and oats were horse drawn and when the carting was carried out, pitching on to the wagons and from thence to the ricks was all hand work, and much sweat was lost in the progress.

A great spirit of camaraderie existed between the workers, however and there was never any bad language or smutty talk. Father would not have approved of that. The work went with a swing, weather permitting. In addition to our own little staff, Father, Harold, Jerry Jennings and Harry Legget, we could always rely on the help of an additional band of helpers, Artie and Bill Longland and Bill Cooper, all willing workers.

(Breach Farm – Jack Elliot holding the bull)

There was much fun, and some relief, when at the end of a long afternoons sweating, Mother and maybe visiting friends and relations would bring out a large dixey of tea and baskets of sandwiches, cakes and scones and we would all break off, try and find a bit of shade and relax for half an hour. How loth we were to start again. Muscles would ache, joints would creak, and it was a while before we got back into full swing again. Those were the times when visitors thought that haymaking were such rollicking times in the country.

The hay and corn ricks, when completed, were thatched to keep out the wet, until the hay was needed for winter feed or when the corn needed to be threshed. The ricks were thatched with sedge which was cut from the narrow strip of land known as the Sling.

The main carrier which when needed, conveyed the water from the river to the water channel that ran around the outside of the Big Ground, following and almost parallel with the course of the main river. On this narrow strip of land between the two watercourses, the Sling, grew sedge in abundance, plenty for thatching requirements. This area was the natural habitat of wild duck, moorhens, coot, sedge warblers, dabchicks, the occasional snipe, water rats, snakes and, in the summer, a host of mosquitos, damsel flies and numerous other insects and wildlife. One sometimes would see an otter or a fox and often watch the ungainly flight of an old jack heron as he floated above looking for a feed of fish in the river.

(Water channel with Breach Farm in the background)

At the far distant corner of the Big Ground was a small pit where we dug gravel used to fill in any unwanted depressions such as in gateways etc. Beyond the gravel pit we crossed the main carrier and came upon another strip of land that that reached up to what we knew as Six Hatches. Across the river at this point, as you may suspect, were six wooden hatches. Flanking this strip of land was a hazel coppice, narrow and on rising ground and to our right. This, on the old map is shown as Breach Sling Copse.

The hatches were used to facilitate the flooding of the water meadow. They were lowered to the required depth to send the water along the main carrier to where it was needed. Near the hatches, which were situated almost in the lee of what was known as Lloyd Copse, was erected what became known as the Fisherman’s hut. This was for the benefit of those fishermen who rented stretches of the water for their leisure pursuits.

The stretch of river running through Breach was looked after by a keeper, Charlie Terry. He was a solidly built, eighteen or nineteen stone and could be a terror to any poachers who came across his path. To us, with livestock on various parts of the farm he could be, and often was, a great help. If he found any signs of trouble among the animals, he would endeavour to put it right but if it was beyond his power to do so, he would immediately come and tell us of it. Charlie was quite a character and was known in all the local pubs for his partiality for a drop of he “strong stuff”.

Most of the area excavated by Halls for gravel was used by us for root crops etc. and, on occasions, for oats. We sometimes grew quite exceptional crops there. This was partly due to the position of the Mount piggeries on the upper side of the lane. The tanks which collected the effluent from there were emptied by a pump over on to the top of the field and, as the ground sloped away, this soaked over a considerable area. We have grown marrow-stemmed kale to over six feet tall and as thick as a man’s arm. To cut it for carting out to feed the cattle we had to use a good stout billhook and an equally strong arm. It was on that land that, nearly seventy years ago, I first learned to plough with a pair of horses and a single furrow plough. Not long afterwards I was ploughing, in Canada, with four horses and a double furrow plough.

In later years, partly at the instigation of my younger brother, Harold, Dad bought a tractor – an old standard Fordson – and the horses were sold. Dad was sorry to see the horses go and, to a lesser extent, so was I. He had worked with horses all his life and, even during the first world war, had served four years in India with a horse regiment. I, too, was brought up among them; we always had a pony and trap and, at one time, a wagonette and ralli cart. They were our means of going to town or market or even going out for an evening’s ride. It soon became obvious, even to Dad, that a tractor made sense but, even then I’ve known the time when the machine got stuck in and had to be pulled out by old Captain or Prince.

Also, the companionship of horses, when used daily and all day – is such that a tractor driver couldn’t imagine. If he’d been caught talking to his charge as we talked to ours, he’d soon have been locked up.

On the north side of the farm was a property belonging to a Mr Matthews. He was a Boer from South Africa but was in residence here for only a few months of each year. His house, Stoke Lodge, stood at the end of a beautiful avenue of beech trees and was quite a picturesque place. A Miss Marks was his housekeeper, and another old chap looked after the garden and grounds.

(Stoke Lodge, Bishopstoke)

The place is marked on the old map as next to Copse House Farm. An old donkey was kept there which was used with a small cart for transporting goods and produce about the place. When that old Moke was out in the fields he would often bray, and I swear he could be heard up the valley halfway to Winchester.

(Donkey and cart decorated for Bishopstoke Carnival at Copse House Farm)

When Mr Mathews died his property, or part of it, was bought by Mr Bucket, a farmer from Allington Lane. He was related to the Coombes family, timber merchants from Eastleigh. As a consequence, many of the beeches in the avenue were cut down and this left a scene of devastation.

There were twelve or more acres of grassland of the Copsehouse Farm adjoining the fields of Breach and Dad was able to rent them and they made a useful addition to his own acreage.

All our top fields and a considerable portion of those extra acres were the site of gravel excavations and, though they have been filled in, grassed down and landscaped and look quite attractive, I’m afraid they have lost much of the attraction they once had, for me, at least.

I must make mention of Woodpecks, the small field just inside the Mount gates. We often kept dry cattle and heifers there and, in winter they had to be fed daily. We kept an old wagon out in the field in which we kept hay and cake. It was often my job to go and dish out some to the animals.

Coming up the lane from the farm I went along a path that went in at Piggery Corner and led along the lower side of the Mount gardens, by the ornamental steps and eventually to the bottom of Woodpecks. At the start of the path was a large rhododendron which always bloomed in February, whatever the weather. The path from here was overgrown and dark, even in daytime.

Often my little trip took place at about five thirty in the morning and at that time of day I reckon it was the darkest place on earth. We never carried a light of any sort and would have deigned it to do so even if it had been suggested. The only times I found it a bit startling was when I disturbed a roosting pheasant or wood pigeon, and they swooped across my path with a sudden whirring of wings. Remembering the time of morning and the fact that I had only just got out of bed, do you wonder I was startled? All sleepiness was immediately dispersed.

The early Springtime was a favourite time of year for the womenfolk of our family to visit Woodpecks as they could pick armful of lovely little, short-stemmed daffodils.

To this day there are, on the upper side of the field, just inside the Mount gardens, some huge fir and pine trees. I knew an old, retired gardener who told me that, as a boy, he had fetched these trees, as seedlings from Horton Heath. He was a delightful old gent of a well-known Eastleigh family, the Mariners.

Having spent so much time at Breach there are so many memories I can recall that it is not possible to record here and, indeed, were I to attempt to do so, I would soon become a bore. However, I will still mention just a few more and risk doing so.

While there we attended the little chapel at the bottom of Spring Lane.

(The Tin Chapel in Spring Lane near the new Post Office)

It stood on the site of what is now Nick’s Fish and Chip Bar and the Off-Licence. It was a long rough walk, and we attended in all weathers. My brother and sister also went there to Sunday School. It was there, too, that on my first Sunday evening home after returning from Canada, I was introduced to the girl who, for the past fifty-three years has been my wife. That was about the best thing that ever happened to me.

That walk down from the hospital to the farm could be a rough old trip at times. There was no lighting of any sort and my Mother and sister have each made the journey scores of times with never a qualm – or a light.

Sometimes, on a moonlit night, we would see a fox, or a badger cross our path. At times the fog would be so thick and dense that we, quite literally, could not see our hands in front of our faces. At other times it could be blowing and raining so hard that we had to battle against it.

Because we had little option, we became used to it and so accepted it. There were also occasions when we were more than compensated by a beautiful moonlit night with the frost silver on every twig and branch. Harold and Maisie attended the school opposite St Mary’s Church and they too, had some rough trips.

(The old Bishopstoke Boy’s, Girl’s and Infant schools)

Our nearest bus stop, to go to Eastleigh was at the corner of Church Road and St Margaret’s Road. The fare was one (old) penny. Later the buses ran up to the Foresters Arms at Stoke Common. This was twopence each way or threepence return.

(Foresters Arms at Stoke Common)

Opposite the Foresters Arms was Mr Billy Woodford’s blacksmiths shop. He, and his son, Basil, shod all the local horses and repaired all sorts of broken machinery. They also re-tyred wagon and cartwheels that had shrunken during long, hot spells of dry weather. I was always pleased to take our horses there to be shod; it was always an interesting experience.

(Woodford’s Smithy at Stoke Common)

Speaking of getting new shoes for the horses reminds me of seeing Dad sitting in the light of an old oil lamp, snobbing our boots. The rough road played havoc with them. He always bought the leather from Mr Harry Fellows the harness maker in Market Street, Eastleigh. When my own family were growing up, I had to follow Dad’s example and become something of a snob.

An annual event that I feel I should mention was when the threshing outfit came. This event was greeted with a certain thrill by us youngsters but with mixed feelings by others. It so interrupted the peace and quietness with noise, dirt, dust and constant comings and goings, all hustle and bustle. Mother was always pleased to see the back of it.

On a prearranged date we would hear the deep chug of the steam engine as it laboured up over Stoke Common hill and then we’d watch it come down over the hill here, a veritable train. The traction engine would be pulling the threshing machine, behind which was the elevator, the driver’s sleeping cabin and a water cart. This was all manoeuvred into position by the corn rick and needed quite a bit of setting up. The old thatch was torn off and two men mounted the rick, ready to start pitching the sheaves to the cutter standing on top of the drum. One man would be standing ready to attend to the stacking of the grain when it started to emerge from the rear of the machine. Another was needed to keep the cavings clear from beneath the drum. No one relished that job as it was the dirtiest, dustiest job imaginable. When the engine driver saw that his engine was correctly lined up and everyone in position, he gave the signal, and we were off.

The engine chugged away, the drum rumbled deep throatedly and, as the men on the rick got progressively lower, so did those building the straw rick get correspondingly higher. The filled grain sacks were carried away to the barn and the water cart had to ensure that the thirsty engine didn’t run dry. We’d stop for a mid-day break and then we were of again. When we shut down for the night the driver and his mate slept in their little caboose. As the hustle, bustle, clatter and hiss of steam died away the silence that followed was almost uncanny.

The corn rick had been built on a bedding of faggots, hedge trimmings and the like to keep the sheave up out of the dampness. In this bedding the rats had made a nice comfortable home, with well-stocked larder attached. They objected to being disturbed and, at the last lap there was much frenzied running, leaping and squealing as they tried to make their escape. A circle of fine mesh wire netting around the base of the rick checked their endeavours and many suffered at the hands of those wielding sticks, prongs or any other weapon that came to hand. Those that escaped these weapons ran the gauntlet of the dogs who were having the time of their lives. This may sound very bloodthirsty but was actually a necessity as those rats had already destroyed a large quantity of grain and, if left to breed would do more untold damage.

When the whole operation was finished there remained the job of getting the outfit back on the road again. Remembering the steepness and condition of our hill, this was quite a clever manoeuvre on the part of the driver. He assembled his machines, etc in the yard, took the engine to the top of the hill and hauled them up, one at a time by using his winch. The conditions prevailing at the threshing scene was one of devastation but, within a few days all was cleared up and tidy again, and the straw rick was thatched.

Having spent so much time at Breach, there is so much that comes to mind, things to do with family life, farming too, many happy ones, some sad, some disturbing but from all of which there’ve been lessons to be learned.

Gradually, over the years, our ties with Breach have become more tenuous. When I married, we moved to a little house in St Margarets Road; Harold married and lived and farmed on what is now the Longmead housing estate and for the last forty years he’s lived in Queensland, Australia. He visits us from time to time. Maisie married, their first child was born, and they moved to lower Eastleigh. Dad carried on at Breach for some time and then, in about 1961 he retired, and he and Mother went to live in a bungalow in Chandlers-ford. He sold the farm to a Mr Dance who farmed it for a few years and then sold out to Halls, the gravel people.

Time passes inexorably and with it brings change and, often, sadness.

Mother, Dad, Maisie and her husband, Bill have all left us. The connections with Breach have become more tenuous and it is only on the odd occasion that I walk around the old place again.

The house is just a ruin; the oak tree opposite has gone as also the old barn and bull pen; the cow stable is still standing but in a sad state. The water meadow is neglected and the fields used only for grazing cattle and horses. A large modern barn has been erected near the yard, winter shelter for cattle. We would have loved a barn of these proportions but now, to me, in the old setting, it looks so incongruous.

The old place looks derelict and depressing and, as I stand and ponder, I get a bitter-sweet feeling and though I often can’t resist a visit, yet I am glad to come away.

As I have already stated, the reason I started writing these lines was in answer to a friend’s query regarding Breach farm. I still haven’t told any history of the place; I must confess, I don’t know it.

I hope he will find a little interest in these lines, even though there is as much – and more – about the Morris family than about the farm. As those who know me will agree, when I get started, whether writing or talking, I tend to get carried away. Please forgive me.

The Water Meadows

(1995)

Dutch engineers are reputed to have brought the idea over to England in the early 1600s.

The laying out, levelling etc was a skilled operation as the object was to flood the land evenly to a depth of three or four inches for periods of three or four weeks. In the winter when there were hard frosts, this prevented the ground from freezing and brought valuable nutrients to the soil. Indeed, after a period of flooding, there was a brown sediment over all.