By Chris Humby

(from a talk first presented in February 2012)

It is possible that the Itchen Navigation is possibly England’s oldest canal, according to Dr Edwin Course in his book, The Itchen Navigation.

It is over 10 miles from Woodmill to Blackbridge Wharf, Winchester and whilst the Itchen Navigation operated commercially, in its modern form from 1666 to 1869, there is evidence that it had been used for transporting of goods from a far earlier date. A charter in 960 A.D. relating to Bishopstoke Manor refers to a staithe, which is a place where boats were unloaded, on the west bank of the river. The first record of the River Itchen being made navigable is in King John’s reign (1199 – 1216) when, Bishop Godfrey de Lucy used the Itchen to bring stone from Portland, in Dorset and Caen, in France, for use in the construction of Winchester Cathedral. It is believed that he used the Itchen to transport the building materials because it was easier than trying to carry the material overland.

The Itchen Navigation was defined by an Act of Parliament in 1665 which specified that the river should be made navigable and passable for boats, barges, and other vessels. The necessary improvements to irrigation, new cuts to reduce distance and locks, to retain sufficient water to float the boats, was not completed until 1710, and then only the section from Winchester to Woodmill. Not to Alresford, as had been originally intended.

The plan was not without controversy. The river was a valuable resource, used by mill owners to provide power to grind corn and, by farmers in winter, for the flooding of water meadows to gain an early advantage for spring planting. The Itchen Valley between Allbrook and Woodmill is flat, wide, and undoubtedly shaped by deliberate flooding over many centuries. There were concerns that the construction of locks would impact the flow of water and that this would affect the traditional livelihood of landowners in the Itchen Valley.

In all there were 6 Acts of Parliament relating to the Itchen Navigation. The initial act of 1665 gave a transport monopoly to a group of investors to carry out improvements on the Itchen. In 1767, a second act was instigated to appoint a commission to review charges and practices on the Itchen Navigation. The third act of 1795 included powers to extend the Navigation from Woodmill downstream to Northam. Perhaps, more importantly today, this act made access to the bank of the Itchen Navigation free to the public. The fourth act of 1802 went into considerable detail about carriage rates, and about works required to bring the Navigation up to standard and about operating details, such as rules for working the locks. The rule, quite sensibly, was that any vessel going upstream which was within a hundred yards of a lock, had precedence. In common with other waterways, distance posts were set up 100 yards below each lock. There continued to be issues relating to management of the Itchen Navigation, particularly the section between Bishopstoke and Woodmill, and the fifth Act of Parliament in 1811 raised the tolls so that repairs could be undertaken. Interestingly, if flooding occurred, owners of the meadows were granted, by this Act, the right to open sluices to prevent flooding, where previously this had been under control of the owners of the Navigation. A final act in 1820 authorised the increase in tolls above those stated in the act of 1811.

The ownership and management of the Itchen Navigation was subject to much legal wrangling from the mid-1800s. Despite the impact on the Navigation from the arrival of the London and South Western Railway Railway and the demise of the Navigation as a commercial operation in the late 1860s, there was an attempt in 1911 to resuscitate it as a commercial operation, but it failed.

The Romans are known to have used rivers and developed waterways for transportation in the UK. They would have used boats a lot smaller than the Roman war galleon shown in this picture. It is probable that the Romans were the first to put the River Itchen, or part of it, to commercial use. Winchester was an important Roman settlement, Southampton a natural port. Yet the roads or tracks between the two would have been relatively difficult to negotiate by horse and cart. Roman remains have been found at Chickenhall and near the railway line in Twyford Road, Eastleigh. Roman coins and pottery have also been found along the banks of the River Itchen at Bishopstoke. This would indicate some type of Roman settlement existed in the area. It is not beyond reason that the water levels and tidal flows permitted cargo to be carried on the River Itchen, possibly as far as Winchester at this time.

Raids were recorded in Hamtun (Southampton) in 1001 by Danes and it is highly probable that Viking longships were hauled on the Itchen and used to carry away plunder. Sails and oars would have been of no practical use in the confines of the river and, most likely, on a raiding mission the boat would have been hauled by manpower, ensuring of course that enough energy remained for pillaging.

The design of a Viking longship, as shown here, is not dissimilar to that of a canal barge or narrow boat. It has a shallow draught requiring little depth of water in which to sail, can carry cargo as well as personnel and is manoeuvrable. The Vikings had a fearsome reputation, yet modern belief is that they were a civilised society with a highly developed social culture. It is certainly evident that a high degree of skill and craftsmanship was used from the design and construction of these Longships in the Viking Museum in Oslo.

In its final form, the Itchen Navigation had 15 locks and 2 half locks (with a single pair of gates each) with a combined rise of 105 feet (32 metres) from the sea level at Woodmill to Winchester. The locks could pass boats about 70 feet long with a beam of 13 feet (21.3m x 4.0m). The barges used could carry between 25 and 45 tons, but, often, poor maintenance of the waterway meant a full cargo could not be carried. This picture is typical of narrow boats that worked the canals in London and the Midlands. These boats were equipped with a cabin and families lived on board. The cabin of a narrow boat was tiny and rarely more than 10 feet long, which resulted in a rather squalid environment. The question is, were these the conditions typical for barges on the Itchen Navigation. It has been suggested that boatmen on the Itchen Navigation lived in houses as they could travel to Winchester and back in a day. The few pictures, that exist, of barges on the Itchen Navigation show no provision for shelter or accommodation. It is probable that the bargemen did live in cottages. There is evidence that boatmen lived in houses, particularly in the period towards the end of the Itchen Navigation, when records from County Assizes refer to cases relating to misdemeanours of bargemen who lived in Bishopstoke and Winchester.

I do however refute that bargemen could have travelled the length of the Navigation and back in a single working day, every day. It is just over 12 miles from Northam Quay to Blackbridge Wharf in Winchester. Standard walking pace over an even surface is around 4 miles per hour, so in theory, it could be done in 3 hours, but we need to be realistic. Add the time to transit a lock and the time increases significantly. The poor horse also needs to accelerate to constant pace after each lock, against the flow of the river, and this would also add some additional time. 15 or 17 locks at, let’s assume, 20 minutes per lock could add nearly 6 hours to the journey. So now, even if the locks can be transited more quickly, we have a probable journey time of 9 to 10 hours or more. Let us examine another possibility. If we assume that the boatman and his family lived mid-way between Southampton and Winchester, then the journey time from home to wharf and back to home would be 5 or 6 hours. This may have been sufficient to permit cargo to be loaded or unloaded to give a likely working day of around 12 hours. In this hypothesis, a barge family would have been able to maintain a permanent residence at a mid-point between Southampton and Winchester and a cargo loaded one day could be delivered and unloaded the next.

The most logical mid points, with an established residential community on the banks of the Itchen Navigation would have been somewhere like Bishopstoke, Allbrook or Shawford. At a steady walking pace, a horse can move fifty times as much weight in a boat as it can with a cart on old fashioned roads, so it is easy to understand the economic advantage of a canal system at the time. Horse boating, for all its apparent slow romantic grace, was not for the fainthearted. It was very hard work requiring skilled judgement and experience. It needed at least two people to work a horse drawn boat, one to steer and the other to drive the horse. A third hand to set the locks would be a bonus but, on most canals, the income possible from one boat would be rarely sufficient to pay for more than a crew of two. The Itchen however had the added complication of a fast-flowing current. Every boats horse or horses needed a stall in a stable at the end of every day’s journey. A hot and tired horse cannot be put out in a cold field for the night, so every regular stopping place had to be equipped with stabling, a supply of high energy food (for the horse) and probably a blacksmith to be on hand for shoeing, should it be needed. A tavern would also be a desirable feature for the bargemen. This would add support to navigation workers living in a mid-point community. There is however, as with all good theories, a flaw in this hypothesis. With the horse tucked up in his stable and the family cosy in their warm and comfortable cottage, where did you leave the boat? There would have had to be an area set aside where boats could be tied up safely. Secondly, who was looking after and protecting the boat? The contents and cargo of coal or grain would have been vulnerable to pilfering if left unattended, so a protected area such as a wharf would be needed. We have heard that there was an unloading place at Bishopstoke Manor in 960 AD. Although there is no trace today. According to Dr Edwin Course, there was a wharf on the Itchen Navigation at Bishopstoke, it was located between Stoke bridge and Bishopstoke lock. Unlike most canals in the country where barges would have had to travel long distances and families would live and work on board, there is some evidence that bargemen, on the Itchen Navigation, were employed to work the Navigation on behalf of a barge owner and because of the relatively short nature of the canal, a nomadic family life was not necessary. We may never know exactly how the people who worked the Itchen navigation lived their life. I will leave that to you and your own imagination.

Let us start to explore the navigation, starting at Woodmill.

The current Woodmill was built in 1820 after the previous mill burnt down. It is probable that a mill has stood on this site since before Doomsday. The mill ceased operating in 1930. This picture dates from about 1890. Woodmill’s most notable occupant was Walter Taylor. Taylor served an apprenticeship in Southampton as a block maker. Rigging blocks were used for ships of the Royal Navy. Taylor acquired a block making business with his father and patented the first power circular saw to mass produce the rigging blocks to a consistently high standard. He became sole supplier of rigging blocks to the Royal Navy in 1759 and moved to Woodmill in 1781 to expand his business. At the time of his death, in 1803, he was supplying 100,000 rigging blocks a year.

This picture shows workers outside Woodmill Flour Mill and is thought to date from the early 1900s. Woodmill lock was constructed adjacent to the mill near the tidal limit of the River Itchen. It was a sea lock with a masonry chamber. Last reconstructed in 1829. It had two pairs of lock gates pointing upstream to retain water in the non-tidal river, plus a third pair, pointing downstream, to prevent very high tides from flooding the navigation with sea water. A wooden bridge used to carry the road over the chamber at an angle. In those days… Woodmill Lane would have been little more than a farm track. This lock remained in use for barges going upstream to West End (Gaters) Mill for some years after traffic ceased on the rest of the Itchen Navigation.

There has been a bridge here, at Mansbridge, since at least Saxon times and for many centuries. Mansbridge was the lowest crossing point of the River Itchen. The old Mansbridge is a stone structure built in the early 19th century with a circular arch and short causeways on either side.

By all accounts Mansbridge was a challenge for barges on the Itchen Navigation, whichever direction they were travelling. For boats, the bridge has less than 6 feet headroom, even at normal water levels. The low level of the bridge required barges going downstream to load up with ballast if they were not carrying a return cargo to Northam. Where would they have been able to do this? Perhaps the wharf at Bishopstoke? The water coming down the river is channelled under the bridge and the narrow nature of the bridge causes the water flow to increase rapidly at this point. This makes it difficult for boats trying to proceed upstream. It is probable that when bringing barges upstream, they had to be winched through the bridge, against the current.

Above Mansbridge, the main River Itchen was navigable for about 600 yards to Gaters Mill. The Itchen Navigation cut to the left, almost immediately above the bridge.

Gaters Mill is a group of buildings sited around a mill pond. There have been mills on this site dating from around the 14th century. Fulling mills occupied the site until 1685, when a paper mill known as Up Mill was established, belonging to the company of White Paper makers, who were granted a charter by James II. Nine of the fifteen members of the company were French refugees. In 1702 another Huguenot, Henry Portal joined the company. In 1718, he set up a paper making mill at Laverstine, near Whitchurch, where in 1724 he obtained the contract for making bank note paper. Gaters Mill stopped the manufacture of paper in 1865. The Mills were largely demolished and rebuilt for use as flour mills. A major fire occurred around 1916 damaging the buildings, several of which were replaced.

This is believed to be a picture of Conegar Lock from the early 1900s. Although badly dilapidated, you can see a wooden bridge crossing below the lock. This bridge carried the towpath from the east side, which it had followed from Mansbridge Lock to the west side.

The first highway bridge to cross the navigation after Mansbridge was at Bishopstoke and this was the most southerly of the highway bridges owned by the Navigation Company. There was a long history of lack of maintenance on the navigation and by 1880 responsibility for bridge repairs was handed to the local highway board. This iron span bridge was built in 1900 as part of the construction of a road from Bishopstoke to the new town of Eastleigh. The earlier design and construction of the bridge over the navigation at Bishopstoke is not known, although it is probable that earth mounds were constructed on either side of the waterway to permit the passing of barges, and timber planking laid between. The bridge over the railway by Eastleigh Railway Station is, whilst larger, of similar design with man-made earth banks forming Station Hill and Carriage Works Hill. When this picture was taken, water levels were particularly low, barely reaching the ankles of the children paddling. Whilst water levels nowadays are higher, barges would not be able to pass under the bridge that now straddles the old canal.

The River Itchen at Bishopstoke, some years after the navigation had ceased operating, became an attraction for more leisurely pursuits. We know that water and children do not mix, particularly where soap is concerned, but as attractive as the river and associated scenery appear, there is a more sinister element for the unfortunate and unwary. There are a number of reports of children drowning on this section of the river. The following is an example that appeared in a newspaper articles of the time. The grammar and use of language have changed over the years. This is a quote from the newspaper, as it was written. An article titled “Bishopstoke – A Child Drowned – A Witness Censured” appeared in the Hampshire Advertiser on August 31st, 1892. “The inquest on the body of a little boy found in the mill stream on Friday morning was held at the Anchor Inn on Saturday afternoon. Frederick Jennings, aged 6 years, was from London and staying with friends of his family in Eastleigh, for the benefit of his health. A lady called Rhoda Vince stated, to the coroner, that she offered to take Freddie with her and her own little boy, her niece, and her little girl on a walk to Bishopstoke. They left home at 3.30pm. Her little boy wanted to go fishing and herself and niece sat down on the bank, while the other children played with the water. They left the bank and walked in the direction of the village and did not notice but that all the children were following. When going through the village her niece noticed that Freddie was missing, and her own little boy said he thought he had gone back home. They continued their walk and on reaching home, about 5.30pm, she asked and was told, that Freddie had not gone home. They had their tea, and then, went out to look for him. They did not find him and by 8.00pm, went to the Police station to report him missing. The body of Frederick Jennings was discovered at 6.30am the next day by a worker from Bishopstoke mill, whilst clearing weeds from the head of the mill, in about 3 feet of water. The Coroner, in summing up, said it was an extremely sad case. No doubt Mrs Vince’s intention in taking the child out was with a kind motive, but kindness also carried with it responsibilities. To take a strange child by water required extra care. That, however, had not been shown by Mrs. Vince, and judging from her evidence, she troubled but very little about it. He was sorry to have to say so, but he must do his duty, and though it was not a case of criminal neglect, it was a case of gross culpable neglect and it would be well for Mrs. Vince to remember what she had said. The jury found that the deceased came to his death by drowning. The Coroner called Mrs. Vince forward and expressed his own and the jury’s view upon the case. The witness went into hysterics after the censure by the Coroner”.

Another inquest at the Anchor Inn, also relating to a 6 year old boy, was reported in the Hampshire Advertiser on October 17th 1900 titled “Child drowned at Bishopstoke” Ellen Court, a child of nine years, living at 183, Desborough Road, Eastleigh, was called as witness and stated that ”she went to Bishopstoke on Saturday morning with Alfred William Laudray, aged 6 years, who she saw slip and tumble into the water. He had been walking along a plank, putting his feet down into the water. She saw him seem to slip, and then fell in. She was then some little distance away. She next ran to tell his mother. Another witness, Frank Collins, residing at the keeper’s cottage, Dutton Lane, Eastleigh, said he met a little girl on the Eastleigh side of the barge bridge, and she told him that someone had fallen into the stream. He got his grappling irons, and went to the spot indicated, and at first found only the deceased child’s hat, but some-time after, on grappling again, he found the body right at the mill head, in about 6 feet of water. The jury brought in a verdict of “Accidental death due to drowning” and added a rider recommending that the stream should be fenced in at the Mill head.” The fence was installed and can be seen at the bottom of this picture showing the new shops in Riverside.

Not all tales relating to the water surrounding Bishopstoke Mill are tragic. The Hampshire Advertiser, on Saturday November the 7th 1868, published an article titled “A Days sport with the Cormorants at Bishopstoke”. “Mr. Chamberlayne of Cranbury Park, near Winchester, invited Mr. Salvin to demonstrate the fishing skill of his Cormorants at his mill in Bishopstoke. About 2.0’clock in the afternoon of the 7th of October the neighbourhood of Bishopstoke, on both banks of the river, was crowded with spectators to witness the prowess of the two feathered fishers. Mr. Chamberlayne’s well-appointed carriages, first drove up, followed by Mr.Standish, master of the Hursley fox-hounds and Mrs. Standish. The lawn at the water’s edge was crowded with well-dressed ladies who had previously arrived, and the banks were studded with country folk, all anxious to “get a look at the river poachers”. Mr. Salvin appeared in a real waterproof suit, whip in hand, followed by two stalwart men carrying the birds in a sort of palanquin. Upon being removed from this, and at the word of command, they flew into the water just as a pack of hounds are hied into cover. In less time than we can take to record it, each bird was playing a fish, and when each had pouched two fair sized trout, attending the call, landed and disgorged their prey. This went on for at least two hours, much to the delight of the spectators. When the sport was concluded, Mr. Salvin rewarded his birds with the fish they had caught.

Let us return to the tranquillity of the Itchen Navigation. It is difficult to imagine that this was once the location of Bishopstoke Wharf. We have no record of the appearance of the wharf, nor how it operated, however with the proximity of Bishopstoke Mill and Barton Mill it is highly probable that this was a site of some activity for the transfer of flour to Winchester, Southampton, and the Channel Islands.

Bishopstoke lock, typical for locks on the Itchen Navigation was built with turf sides. Wooden piling existed in the chamber of the lock, which would both protect the sides, and ensure that descending boats were not caught on the sides when the water level was being lowered. Sluice gates have replaced the upper lock gates and brick and steel piling have replaced the original sides of the lock in this picture.

The walls that once supported the gates at the head of the lock have been strengthened to support the three sluice gates which regulate the flow of water. This lock basin appears to be considerably wider than other locks on the mid-section of the canal and this is either because a wharf that existed near this location or has been created due to later alterations.

This section of the navigation, immediately above Bishopstoke lock is, most reminiscent of how the waterway appeared on the lower sections that are now dry. It is not overly wide, and there would not have been a great deal of clearance for two barges to pass one another. The tow path is on an embankment, which falls away towards the playing fields which are at a lower level. Again this must also reflect how the lower sections of the canal were constructed. It also indicates why maintenance was such an issue to those that worked or lived alongside the navigation. Failure to maintain the banks would have resulted in reduced water levels for the navigation and unwanted flooding to adjacent meadow and pastureland. Nowadays the banks of the canal are festooned with trees and shrubs. When the navigation was operational this could not be allowed to occur, and vegetation was probably held at bay by free roaming cattle grazing up to the bank. The tow path is relatively narrow, although certainly sufficiently wide enough for a horse and handler. On certain embanked sections, however, it must have been difficult for two horses to pass one another and it is probable that protocols were applied to manage these issues.

There is a record, dating from 1618, that shows a footbridge over the River Itchen leading to the churchyard and in 1892 it is listed as forming part of a footpath to Bishopstoke Village, Crowdhill, Colden Common, Owslebury and Marwell Hall. The map pictured dates from 1840 when the Itchen Navigation was fully operational. The old Saxon church would have been a landmark building on this stretch of the water as would the later St. Mary’s Church, built in 1825.

Grand houses, such as Itchen House (the Cottage) and the Mount were constructed before the end of commercial operations on the navigation and would have had a major impact on the landscape in the vicinity. Harold Woodford recalled that in the early 1900s, when Mr. Bourne, a man of some influence, took up residence in the nearby Manor House he objected to the public having access to this bridge. Mr. Bourne approached Harold’s father, who was blacksmith at Stoke Common, to demolish the bridge so that it could not be used. Mr. Woodford senior replied, “it would be more than I dare do”. I am grateful that Mr. Woodford had the courage and foresight to defend a right of way that we still enjoy and benefit from today and refused to have any part in its destruction.

This is the St. Mary’s Church which replaced the old Saxon Church. It is believed that Christianity has been worshipped on this site for over 1000 years. To the right of the Church is Itchen House (once known as “The Cottage”).

The gardens of Itchen House or “the Cottage” as it was known in Admiral Sir Henry Keppell’s day, straddle the River Itchen adjacent to the Itchen Navigation at Bishopstoke. Such a location was perfect for the Admiral to develop his interest in fish breeding. He diverted part of the river so that a new cut flowed between the flower and kitchen gardens and through his summerhouse. There, using a system of tanks and trays, he developed a trout hatchery. He was advised in this venture by a gentleman called Frank Buckland. Frank Buckland trained as a surgeon and, for a while, took a commission in the Life Guards. His real interest and passion was in natural history and some of his articles on the subject were published in 1837 to great acclaim. He was a bit of an eccentric. A larger-than-life character, he stood 4 feet 6 inches tall. He devoted his life to fish breeding and became leader of The Society for the Acclimatisation of Animals in the UK. The Society wanted to find out if various exotic animals could be imported for food and he became known as “bring em back alive and eat em Buckland”. His diet included Squirrel, Rhinoceros, Giraffe and Bison.

Admiral of the Fleet the Hon Sir Henry Keppel G.C.B. D.C.L.

Frank Buckland

Admiral Sir Henry Keppel wrote in 1863: “In the upper part of the summer house I had a tank and a small stream of water was introduced into a succession of troughs of spawn. These overflowed into each other. It was great fun watching the tiny things come to life and gradually increase in size, until it was time to put them into the river. Chamberlayne and others, through whose property the Itchen ran, took a great interest in the experiment. From my little preserve on the Itchen, Frank Buckland stocked the rivers in Tasmania with trout, which has proved very successful.” It was Frank Buckland, in conjunction with Admiral Sir Henry Keppel, who donated 1,000 eggs from the hatchery in Bishopstoke, that introduced trout to Tasmania. From there they were bred and spread to the rest of Australia and New Zealand.

This is the point, above Bishopstoke, where the River Itchen and Itchen Navigation merge. The River Itchen can be seen flowing to the left towards the Cottage, whilst to the right is the beginning of the cut of the Itchen Navigation.

For about half a mile between Stoke Lock and Withymead Lock, the mainstream of the River Itchen was used as part of the navigation. This accounts for the wider nature and curvature of the waterway. This picture shows Barton Bay and the Horsebridge, to carry the towpath and the hatches to regulate the flow of water into the Barton River, which powered Barton Mill. Notice the absence of vegetation along the tow path bank. Cattle were still able to graze the banks when this picture was taken in the early 1900s and perhaps this picture reflects how this stretch of the Navigation would have appeared, when it was a working waterway, rather than the appearance that we see today. Wildlife and attitudes to it have changed over the years since the canal last operated. In August 1865, a newspaper article reported that “Last summer there was capital Otter hunting in the meadows and waters between Winchester and Southampton, and many were killed. Since last October, not a single Otter was seen until 11th August when a very fine one was killed”.

Without commercial traffic, the river and navigation by the late 1800s, had become an area for recreation for the gentry that had built grand houses in Bishopstoke. This is a picture of the boathouse that stood in the grounds of Spring Grove.

The Navigation continued to use the main River Itchen as it headed northwards towards the next lock at Withymead. This section of the river is in the vicinity of the Mount, which was originally built in 1844. As in the earlier picture taken at Horsebridge Hatches there is a complete absence of shrubs or trees along the towpath side of the riverbank.

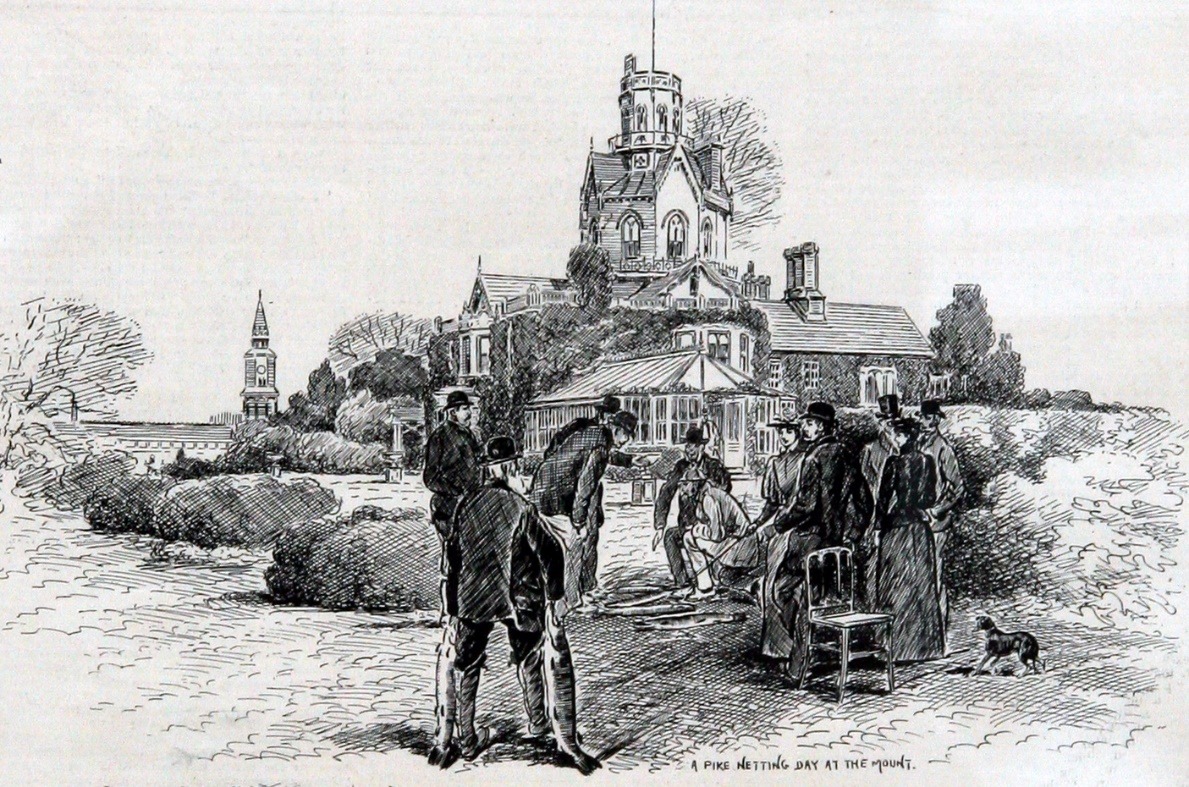

For Victorian gentlemen there was a clearly defined “huntin and fishin” season and Captain Hargreaves, who bought the “Mount” in 1872, was a keen supporter of all things piscatorial. With the Itchen River and Navigation running through Bishopstoke, fishing, and probably poaching, was a popular pastime. The public had enjoyed the right to fish along the towpath until, in 1874, Mr. Chamberlayne, who owned most of the land in Eastleigh, put up notices saying that all fishing rights belonged to himself. In defence of the public rights and a keen fisherman himself, Captain Hargreaves fished the whole extent of the river. He was duly convicted of trespass, lost on appeal, and had to pay costs. Fishing rights must have eventually been resolved for an article containing this picture was published relating to Captain Hargreaves and his fishing activities on the River Itchen in December 1890 in the Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News.

The grounds of The Mount were extensively landscaped and the wooded area that had lined the eastern bank of the River Itchen was transformed into a garden of some significance as can be seen in these sketches published on 13th December 1890. A boat house can be seen on the left. The ornamental bridge and stream shown on the right was situated above the river nearer, to the main house.

This picture of the Boat House near The Mount was from the period when the property had had been bought and rebuilt by Mr. Thomas Atkinson Cotton after 1890.

This picture depicts Mr Cotton standing on the bank of the river whilst his wife, Charlotte and Daughter Ida enjoy boating on the river. Note the grand stairway leading from the house down to the river and the beautiful, manicured surroundings amongst the woodland which shields a view of the house from the river.

The landscaping and gardens were most magnificent, as can be seen from this illustration.

Thomas Atkinson Cotton was born in Yorkshire. Before moving to Bishopstoke, he rebuilt the Mount to his design in 1892, only 20 years after it had been previously built and created extensive aviaries in the grounds to pursue his interest in ornithology. He also carried out extensive landscaping alterations that introduced many new species of flora. Thomas Cotton sold The Mount in 1921. The Mount and grounds became a T.B. sanatorium, which it continued to be after the introduction of the National Health Service in 1948. The clean air, woodland walks and congenial surroundings were an ideal location in which to care for the terminally ill and those that needed recuperation.

This is the point on the Itchen where the River Itchen and Itchen Navigation go their separate ways until they meet again, briefly, north of Brambridge. The main River Itchen bends to the right of picture, towards Breach Farm which can be seen in the distance, whilst the Itchen Navigation veers to the left, towards Withymead Lock and Allbrook.

This picture is believed to be of Withymead Lock, and It is at this lock that the tow path, once again, crosses from the west bank to the east bank of the waterway. Whilst this lock was typical of a lock on the Itchen Navigation, with the head and tail of the lock being of brick construction and the basin turf sided. Dr Edwin Course believed it was unique in so far as a side stream was provided, on the west side, to take off any excess water above the lock rather than utilise vents in the top gates, but from observation there is a similar feature at Bishopstoke Lock also. This picture, although taken a long time ago, shows that the gates have been removed and would appear to have been replaced by a wooden frame with sluice gates at the head of the lock and water spilling over.

The opening of the London and South Western Railway line in 1839 crossed the Itchen Navigation in two places between Withymead Lock and Allbrook Lock. The single arch bridge, originally constructed to carry two tracks was widened, some years later, to accommodate four tracks. Note the workmen’s bicycles leaning against the wall of the arch on the old towpath.

More widening took place during World War II, when railway capacity was being increased, as a preliminary to the invasion of Europe. It is probable that this picture was taken during the first widening, as very little photography was permitted for non-military purpose during World War II, and certainly it would not have been politically acceptable to record preparations for a military invasion.

During the Victorian period houses were built in Allbrook between the two railway bridges, with gardens running down to the Canal. These houses were not built until after commercial operations on the Itchen Navigation had ceased.

The bridge we know as Allbrook Arch was originally constructed to carry the railway over the roadway, around 1838. It is adjacent to the Itchen Navigation, which is itself crossed by a highway bridge, on the far side of the railway. This picture also reflects technology developments in transportation that have been driven by commercial and social change. The canal was quickly replaced after the arrival of the railway because the railway was quicker and more efficient. The motorised vehicle replaced the horse and cart and, latterly, the railway by offering greater convenience and flexibility.

Close to the Railway arch at Allbrook, a sawmill took advantage of waterpower from the river, just like the Mills at Bishopstoke, and Barton, although there was a slight interruption in supply when this water wheel was frozen solid, on February the 8th 1895.

Allbrook Lock, adjacent to the railway arch, was like other locks on the Itchen Navigation, originally built with turf sides. This picture, taken when the lock was still in operable condition, clearly shows that the turf sides have been replaced with a brick lined chamber. It is believed This brickwork was installed when the railway line was constructed alongside, in around 1838 and was probably done to stabilise the sides of the lock which, if eroded, could have undermined the embankment of the railway.

This delightful picture shows a couple posing for their photograph, standing on top of the Allbrook lock gates. The water can be clearly seen to be flowing through channels to the side of the gate and the railway track is clearly visible on the embankment behind them. Above the lock, there is a section of canal that runs about five feet above the level of the surrounding land before it runs alongside the mainstream of the River Itchen, until it reaches Brambridge.

This picture is an etching by the artist Heywood Sumner of the single gates at Brambridge from about 1880. Near here, the River Itchen runs quite close to the Itchen Navigation and Charlotte M.Younge recalls a story about Brambridge Crossing which spanned the River Itchen in Kiln Lane: “In those days there was only a foot bridge across the Itchen at Brambridge. Carts and carriages had to ford the river, not straight across but making a slight curve downwards; this led to awkward accidents.” Writing in “Old Times at Otterbourne”, she describes how a disaster befell the Newton family on their way to a funeral. It was described by one of the bearers as follows: “When the cart turned over, the corpse was on the foot bridge. It was a very wet day, and the wind was blowing furiously at the time. It had a great effect on the cart, as it was a narrow cart with a tilt on, and there was a long wood sill at the side of the river. That dropping of the sill caused the accident. I think there were five females in the cart and the driver. The water was as much as 4ft. deep and running very sharp, so myself and others went into the water to fetch them out, and when we got to the cart, they were all on the top of the other, with their heads just out of the water. They could not go on to church with the corpse, and we had a very hard job to save the horse from being drowned, as his head was but just out of the water.”

The present bridge at Brambridge was constructed by the Highway Authority, after the demise of the canal and the design is similar to Stoke Bridge. At this point, the towpath crosses from the east to the west side. There were two sets of single gates on the Itchen Navigation. Brambridge, as illustrated, and at Shawford. This illustration, circa 1880, looking south from above the lock, shows little water above the gates and, whilst reflecting a time only 10 years since commercial traffic stopped using the canal, it does indicate how fast lack of maintenance impacted on the waterway and surrounding area. It is believed that single gates had been constructed, in these locations, to provide a head of water for mills, situated on millstreams, diverging from the Navigation.

Shawford Bridge is a replacement by the Highway Authority, also comparable to Stoke Bridge. The bridge carries the towpath from the west to the east side of the waterway.

Above the bridge, the west bank is bordered by houses and gardens similar to, but on a much grander scale than those at Allbrook as these pictures illustrate.

Whilst today the Itchen Navigation appears calm and peaceful, many an unwary life has been claimed. There are other salutary reminders that the river can be a dangerous place.

Whilst today the old lock on the Itchen Navigation at Compton appears calm, and children jump into the lock chamber on warm sunny days, there is a salutary reminder to young and old that the river can be a dangerous place. The Hampshire Telegraph on December the 25th, 1852 reported the drowning of George Raynor, aged 45, at Compton Lock, Shawford. It appeared that he was in the habit of bathing there at an early hour every day and had left his house on the 21st of December at 7.00am to bathe as usual. His body was discovered an hour later in three or four feet of water and his clothes were 50 yards higher up the stream where the water was much deeper. The surgeon who examined the body was of opinion that the deceased was drowned, in consequence of an attack of cramp or some other seizure, brought on by staying too long in the water at this inclement season. The coroner’s jury returned a verdict of accidental death.

Official records indicate that the Itchen Navigation ceased commercial operations in 1869, although an article in the Hampshire Advertiser on the 26th of January 1870, reported the death of a bargeman on the canal at St. Catherine’s Lock. This picture of St Catherine’s is thought to be from around 1870. The barge had left Southampton at 11.30 am, with a crew of four experienced bargemen, laden with 27 ton of coals. They stopped at Shawford, at around 8.20 pm where they disposed of two pots of “fourpenny” (beer). Although it would have been quite dark and they had no illumination, they then continued their journey towards Winchester. At St. Catherine’s Lock, Tom Ewens (aged 54) went to check that the swing gates had been closed properly. Ten minutes later his hat was spotted in the water and the stage board by the side of the canal was broken. He could not be seen nor heard. The men would not go to Sam’s, the foreman of the mills for a lamp because he was such an old crab, and because the sawmill proprietor and the bargemen were not on the very best of terms. Instead, they went to the “Black Boy” (a pub near Blackbridge Wharf) to inform the barge owner about the accident and to get ropes and lanterns. They returned to St. Catherine’s Lock about an hour and three quarters after the alarm had been raised. They found the body, ten yards below the pound in about 8 feet of water.

At the time evidence was taken from W. Bulpett, Esq., J.P. as proprietor of the Itchen Navigation. Bulpett informed the court that Henry Palmer, a carpenter employed by Bulpett for over 30 years was employed to look after and keep in repair several locks and stages, including St. Catherine’s Lock. It had been alleged that swing pieces had been cut off from the lower lock gates some time before the accident. Although this did not prevent the lock operating and anyone could shut the gates with their hands, it did make the task more difficult and required somebody to get on the staging to ensure that the gates were fully shut. It was established that one of the swing pieces had had broken off six years earlier, whilst the other had been cut off two years earlier, with the consent of the sawmill occupier, to improve roadway access to the sawmill. Bulpett further informed the coroners court that the sawmill had been let with the proviso that the occupier was not to interfere with the Itchen Navigation or do anything, in any way, to its prejudice, and that he had never been made aware that the swing pieces had been cut off and had never given his consent for this work to be done. The jury found that the stage and locks were unfit for use and dangerous. Henry Palmer, the carpenter, not Bulpett the owner of the Itchen Navigation, was blamed for the defective stage and lock. This case, not for the first time, raised issues relating to the lack of maintenance on the Itchen Navigation. There are numerous examples and councillors from Southampton, in particular, were very derisory of Bulpett and his attitude towards the management of the canal.

This case also gives us a far better explanation as to how the Itchen Navigation operated at the end of its commercial life. It was stated that the barge left Northam at 11.30 am and reached Shawford by 8.30 pm. After travelling for 9 hours, it had not yet reached Blackbridge Wharf in Winchester. Although the men had spent time in the pub, they travelled on to St. Catherine’s Lock where the accident took place. It took a further 1 hour and three quarters to get to Blackbridge Wharf and back, presumably on foot without the barge and, in some hurry. From these statements, the journey time for a horse drawn barge, from Northam to Blackbridge Wharf in Winchester, took eleven or twelve hours to complete. Loading and unloading time would also need to be added and this would indicate that it was unlikely that bargemen, on the Itchen Navigation, would have been able to regularly complete a journey the length of the navigation and back in a single day. We must be careful however to not judge the working day then by todays standards and it is quite possible that, in some circumstance a working day of 16 to 18 hours was undertaken, if you allowed sufficient time for the boatmen to walk to home and back. It is clear that operating at night, without lanterns, was a common practice. What is clear is that the bargemen were employed by a barge owner as their priorities was to report to the owner at Blackbridge that there had been an accident. A crew of four men may or may not have been typical and it is difficult to accept that the owner of the barge could have regularly afforded to pay four men for this journey, particularly as barges in other parts of the country operated with a crew of only two.

There were many issues recorded relating to inadequate repairs and maintenance on the Itchen Navigation. There were claims for damages from neighbouring landowners where their land had been flooded and a particularly interesting case, reported in the Hampshire Advertiser on the 21st of March 1868, relates to farmland at Tunbridge. This is a picture of Tunbridge Lock from around 1870. William Bulpett, as manager of the Itchen Navigation was sued by a Thomas Burton for damage done to the ground by overflow from the canal. It appeared that seven acres of land was affected, and that high grade fertiliser had been applied to the ground and turnips planted prior to flooding. The crop was damaged as the nutrients had been washed away. There was a claim, by Bulpett, that an easement raised the question of titles over the land and, once again, blame by Bulpett was also placed against those that were employed to maintain the waterway.

This path leading to St. Catherine’s Hill was also underwater for about four weeks until the “blow” to the bank was made good. You can see in this picture how the bank of the canal has been raised to separate it from the River Itchen. It was typical of many stretches of the Itchen Navigation that earth banks were constructed to maintain the waterway at a higher level than the adjoining land and river. It does not take a lot of imagination to understand the consequences of the bank being breached. His Honour, in summing up, said it was merely a question of fact. Mr. Bulpett was in beneficial occupation and he was responsible for any damages caused by his neglect to repair the bank. The question for the jury to decide was whether any and what damage there had been. The jury, after a very brief consultation, returned a verdict in favour of the plaintiff and awarded damages of £10, 5s, with costs. An interesting aside in this case is that three absenters from the Jury were each fined £5. They were all prominent residents from Bishopstoke. They were Alfred Barton of Longmead House; George Onslow Dean of Highfield house (Retired officer); and Wilmot H. Waterhouse of The Grove. We will never know why these three wealthy and influential gentlemen did not attend jury service to sit in judgement on a wealthy and influential Winchester merchant banker, although you may wish to form your own conclusion!

When Keats wrote about the “season of mists and mellow fruitfulness”, he was living in Winchester. Every evening he would take a constitutional through the Cathedral precincts, across the College grounds and along the River Itchen to the Hospital of St. Cross. Henry de Blois was appointed Bishop of Winchester in 1129 at the age of 28, he founded the Hospital of St Cross between 1132 and 1136, creating what has become England’s oldest charitable institution. The hospital was founded to support thirteen poor men, so frail that they were unable to work, and to feed one hundred men at the gates each day. The thirteen men became the Brothers of St Cross. Then, as now, they were not monks. St Cross is not a Monastery but a secular foundation. Medieval St Cross was endowed with land, mills, and farms, providing food and drink for a large number of people. In those days water was unfit for drinking so copious amounts of ale and beer were needed.

The early mill on the River Itchen at St Cross belonged to the hospital and flour was ground here for the inhabitants of the alms house.

Wharf Mill at Blackbridge, Winchester, was located at the head of the Itchen Navigation and, although now converted to flats, it was once a thriving Corn Mill. A notice in the Hampshire Telegraph on the 18th of November 1833 advertises the mill to be let in a good state of repair, nearly the whole of the machinery having been new, within a few months. The advert further explains that the mill is at the head of the Itchen Navigation where goods can be exported and imported to and from all parts of the kingdom, at a trifling expense. The mill has a good business to it and is capable of clearing off 15 loads per week. A notice in the Hampshire Telegraph on the 8th of April 1839 advises a further letting being available. The mill has an increased capacity of 30 to 40 loads a week and, interestingly, it is mentioned in the sales publicity that, as well as the Itchen Navigation, one of the stations of the Southampton Railroad will soon be within half a mile of it.

Blackbridge Wharf and the Itchen Navigation terminated just a few hundred yards downstream of this scene at Soak Bridge, Winchester. From here, you can enjoy a short walk downstream to Blackbridge, where the Itchen Navigation terminated and enjoy views of Winchester Cathedral and Wolvesey Castle, home to the Bishops of Winchester for many centuries. At Blackbridge, lean against the parapet and consider the history of the area. The toil of the men that dug the canal by hand and worked the canal for over 200 years and the changes that led to its demise. The Itchen Navigation was frequently subject to disputes, as we have discussed, and, whilst considered important by traders and merchants in Winchester, it was seen as far less important by those in Southampton. In 1767, Edward Pyott became sole owner of the waterway and, it was alleged he operated the Itchen Navigation to benefit himself by refusing to carry commodities for others when this would affect his own business as a dealer in coal and other heavy goods. Winchester merchants petitioned Parliament and in 1767, a body of commissioners was appointed to ensure fair treatment and set rates for the use of the Waterway.

In 1793, the Mayor of Winchester, John Nicholas Silver, under pressure from City merchants, on the 23rd of February, provided 26 bargemen with a certificate of exemption from press-ganging (forced service in the Royal Navy). This gesture was more political than practical as it is probable that neither recipients nor press gangs would have the ability to read; the document would quickly become defaced; and if you woke up onboard ship with a lump on your head, a piece of parchment was not going to be your salvation. This list also indicates that there may have been several barges plying the navigation in its heyday.

Amongst the list of freshwater sailors granted a certificate, by the Mayor in 1793, was a Thomas Humby. It is possible that there is a distant family connection as Humby is a relatively unusual name and the family have lived in the greater Southampton area since the 1700s. If you venture along the canal towards Winchester, you may wish to seek out the ‘pausing place’ along the bridleway at the base of St. Catherine’s Hill. It is a barge shaped stone seat engraved with the names of 5 barge crews, including Thomas Humby.

By 1795, James D’Arcy, a barrister, owned the navigation but the running of the Waterway was left to George Hollis, a solicitor. James D’Arcy wished to raise money to extend the Itchen Navigation from Woodmill to Northam and, in return for the right to sell shares to raise capital, D’Arcy perhaps naively, agreed to fix the chargeable rates then in force and hold them forever. By 1800, George Hollis had acquired all the shares in the Itchen Navigation and assumed control. Further acts of Parliament were passed that permitted an increase in charges, on the Itchen Navigation to counter the inevitable effects of inflation. George Hollis sold his shares in the Itchen Navigation in 1839, but his son, Francis Hollis, stayed on as manager. By 1841, William Whitear Bulpett, a Winchester banker and major mortgagee of the Itchen Navigation, became manager. This is around the time when the London to Southampton Railway was completed and the commercial nature of the canal began to decline. In 1861, Francis Hollis, who claimed to hold three quarters of the shares, demanded that the Itchen Navigation be put in the hands of the receiver. Hollis attempted to remove Bulpett as manager in the High Court and failed, bankrupting himself in the process. By the time the Itchen Navigation closed, around 1869, there were only two barges operating. Some of the bridges over the Itchen Navigation had become unsafe and in 1879, Bulpett was asked to pay for remedial work carried out to Shawford bridge by the Highway Board. Shrewdly, Bulpett claimed the Itchen Navigation estate to be insolvent. When Bulpett died in 1899, possession of the Itchen Navigation passed to his nephew, Charles Bulpett. There was a brief attempt to to re-open the Itchen Navigation in 1911 and a company was formed but never traded, and it was wound-up in 1925. Charles Bulpett emigrated to Kenya and, since his death, it is not known who has rights to the ownership of the Itchen Navigation.

Whilst the acts of Parliament relating to the canal are still on the Statute Book and remain the law of the land, there are also those that have a claim under “squatters rights” as, in the intervening years, they have maintained the bed and banks of the waterway.

This picture of Blackbridge, with Winchester Cathedral in the background, shows an image of the type of barge that is believed to have operated on the Itchen Navigation. Unlike narrow boats which worked the canals of London and the Midlands, these boats are defined as “swim-ended”, which is a boat or barge with a flattened, square end to bow or stern, that is raked to overhang the water.

This oil painting is titled “A view of Winchester from the River Itchen, with a Hay Barge in the foreground and the Cathedral and St. Catherine’s Hill beyond,” and was painted by Frederick Waters Watts in 1843. I have been advised that the title is technically incorrect as it shows St. Giles Hill, not St. Catherine’s. The painting shows a barge approaching Tun Bridge from the south with a temporary canvas shelter at the stern. The reference to “Hay Barge” in the title seems to suggest that this shelter is protecting a cargo of hay. The barge is being pulled by two horses and two people can be seen in the hold. There would have been at least one other person guiding the horses. Near the front is a vertical towing mast. Shelter from the elements and accommodation for those working the barge was not provided. I am grateful to Peter Oates from Southampton Canal Society who has kindly provided a copy of this and the previous picture with some additional information. He has advised me that crews and barges were registered with the Clerk to the Commissioners of the Navigation. It appears that registered crews were usually four or five, but this does not mean that all these people crewed every trip, some could well have been reserves. One part of the journey which may have demanded a larger crew was the passage on the tidal river from Northam up to Woodmill, where there was no towing path. The barges moved with the tide and were controlled/steered by means of long wooden poles (a rudder is useless when the boat is drifting with a current). As shown in this picture, two horses might have been necessary when towing upstream especially in times of higher flow. The bridge shown is of simple, yet effective construction. The design of this bridge also matches the design of those shown in the pictures we showed previously of St. Catherine’s Lock and Tunbridge Lock, and in all likelihood demonstrates how bridges across the Itchen Navigation, such as those at Shawford, Brambridge & Bishopstoke were originally constructed. This picture, better than words, perhaps reflects how life on the Itchen Navigation was, if you ignore artistic licence and accept that the sun did not always shine.

This picture is of the Itchen Valley at Bishopstoke and is an etching by Hayward Sumner dating from around 1880. We should be grateful that because of rights granted by Acts of Parliament relating to the Itchen Navigation, we today have access to a significant stretch of one of the finest, most beautiful, and wildlife-rich Waterways in the UK, and it is on our doorstep. For those of you that may be interested, further information about walks and wildlife along the Itchen Navigation can be found at: www.itchennavigation.org.uk

If you do decide to venture along the Itchen Navigation towpath from Woodmill to Winchester I hope that you may be able to relate to some of the story’s mentioned in this document.

Bibliography

Drewitt, A. (1935) Eastleigh’s Yesterdays, The Eastleigh Printing Works

Hampshire and Isle of Wight Wildlife Trust

Course, Edwin (1983) The Itchen Navigation, Southampton University Industrial Archaeology Group

Young, Charlotte, (1891) Old Times at Otterbourne

The Bishopstoke Connection – An article by Graham Mole

Southampton Canal Society

West End History Society

Hampshire Records Office

Hampshire Library – 19th century newspapers online

Hampshire Museum Services

Additional Information: Joan Simmonds, Malcolm Dale